Can (or should) science prove the existence of God?

A bestselling book in France claims to offer evidence of a supreme being that created the universe, reigniting a debate over the relationship between science and religion

There was a time when the idea of God was all-powerful. Then, not so much: Copernicus took the Earth out of the center of the universe. Darwin removed the human being from the center of evolution. And Freud even took us out of the center of our own psyche. Religious explanations were retreating in the face of greater scientific knowledge. But there are those who argue that things have shifted once more, and that the idea of God the creator is once again gaining ground.

The book Dieu: la science, les preuves (God: The science and the proof) by engineer Michel-Yves Bolloré and businessman Olivier Bonnassies, argues that modern science is inconceivable without considering the existence of God. In France, the book was a publishing phenomenon that sold more than 250,000 copies; it even included a foreword by none other than the Nobel Prize winner in Physics, Robert W. Wilson, the co-discoverer of microwave background radiation, which supports the Big Bang Theory.

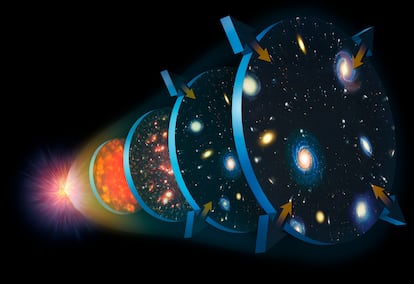

In their book, Bolloré and Bonnassies harshly criticize current materialism and consider some of the scientific discoveries of the 20th century to be “evidence” (though not demonstrations) of God’s existence. In particular, they mention the Big Bang Theory: against the proponents of a stationary universe, which doesn’t have a beginning or an end, the Big Bang Theory provides the possibility of a creator God, perhaps not in the literal terms of the Bible, but a creator nonetheless. In theological language, God would then act through secondary causes: God does not directly create things in the world, but he creates the world in which things then happen through the laws of nature. Curiously, one of the scientists who developed the Big Bang Theory, Georges Lemaître, was not only a cosmologist but also an abbot. The prediction of the Second Principle of Thermodynamics that the universe will end in thermal death, cold and dark, is also a point in favor of the God argument, according to the authors, who consider it “irrational” to be materialistic today.

“Some arguments are very old,” opines Antonio Diéguez, a professor of Logic and the Philosophy of Science at the University of Málaga in Spain. He is referring to the argument of fine-tuning, which is related to the anthropic principle. The former is the idea that universal constants (the speed of light, the gravitational constant and Planck’s constant) seem perfectly adjusted for the existence of life. It seems that someone has done it on purpose… For its part, the anthropic principle observes that the universe seems to have been made with us in mind. Everything fits together miraculously well. “There are several answers to that,” says Diégue. “For example, there may be a multiverse and that this is just one universe out of many, where these conditions exist. Or it could be a contingency: life has arisen due to the fact that these conditions already existed.” One might also point out that, in a differently equalized universe, another form of life could appear, as, in fact, it can appear on other planets.

Thomas Aquinas’s cosmological argument, in which he says that if the universe exists, it is necessary for someone to have created it, resonates. There are other arguments of this type, such as the long-standing and teleological intelligent design argument: if the world is complex, there must be a God who created this complexity. In this vein, the so-called watchmaker analogy proposes that where there is a watch, there must be a watchmaker. For example, for many creationists, the eye’s complexity inspires the need for a great designer of the world, beyond the blind vagaries of evolution. But these are weak arguments.

“I do not need that hypothesis”

In short, the book by Bolloré and Bonnassies does not “prove” anything. In France, Jesuit François Euvé published a response to their book called La science l’épreuve de Dieu? (Science: Is it proof of God’s existence?). He concludes that it is not. A famous anecdote about physicist Pierre-Simon Laplace comes to mind. The scientist went to show Napoleon his discoveries about celestial mechanics, the reasoned explanation of the solar system’s precise dance. Interested, the emperor asked the physicist what God’s role was in all that. Laplace replied: “Sire, I do not need that hypothesis.” If Bolloré and Bonnassies’s book did indeed prove God’s existence, we would probably be living through the greatest revolution in human knowledge of all time. But, for the time being, positions seem intractable; they are where they have always been, and religiosity seems to have remained in its natural field: that of belief.

Beyond this book, the relationship between science and religion has always been complicated. “Since the scientific revolution, many beliefs that appeared in the different sacred books have been refuted, from the movement of the sun and the stars to the evolution of species. God’s hand has gradually disappeared from all fields of knowledge,” says Jorge J. Frías, the president of ARP (Society for the Advancement of Critical Thinking). A major milestone was the trial and condemnation of Galileo for his heliocentric ideas in 1633. Over time, the conflict subsided, partly because of the Catholic Church’s acceptance of scientific ideas, such as the theory of evolution. But other branches of Christianity continue to advocate creationism — creation as literally narrated in the Bible — which causes quite a few conflicts between science and religion in American education.

While one might think that scientists tend toward atheism, there have been all kinds of believers and nonbelievers: atheists, theists (believers with revelation), deists (believers without revelation), agnostics… “Almost all the great historical physicists have been believers in one way or another,” says astrophysicist Eduardo Battaner, author of Los físicos y Dios (Physicists and God). For example, Albert Einstein was a deist, embracing the idea that there is a supreme being, but not a personal one, who is indifferent to our presence and does not intervene in the world. That is not the God from the monotheistic religions. That God sounds more mysterious, immanent, spiritual.

Bolloré and Bonnassies’s book involves Paul Davies, a physicist at the University of Arizona and the author of God and the New Physics. Davies doesn’t belong to any particular creed, but he refuses to believe that the universe is merely a “fortuitous accident.” As Davies puts it, “The physical universe is arranged with such ingenuity that I cannot accept this creation as a raw fact. In my opinion, there must be a deeper level of explanation. Whether we want to call it ‘God’ is a matter of taste and definition.” Philosopher Baruch Spinoza’s position is also compatible with science: God is nature itself. He is everything, not a separate entity that governs the world’s fate. The underlying notion in many of these cases is that there is no need for science to deal with the idea of God, which must remain in the realm of belief or at least theology. “Science does not serve to demonstrate that God exists or to demonstrate that God does not exist,” says Diéguez.

Science and religion

In theory, scientists’ beliefs need not affect their positions and research, but it isn’t that simple. “You have to keep in mind that scientists only have one brain and compartmentalizing it into two modes of operation is artificial and not easy to achieve,” Battaner notes. Historically, beliefs did influence science. Kepler wanted to be very precise in his work to inform the world about how God had done it. Newton believed in the necessary intervention of God for keeping the solar system from becoming disordered. Einstein tried to put himself in God’s shoes to judge his own theories… Would God have done it that way? “When it comes to work, it is not easy to put feelings aside,” Battaner adds.

The compatibility between science and belief has its critics. “Since humans are not objective, some scientists try to turn the matter around to make it fit their own beliefs,” explains Jorge J. Frías. For example, he refers to the paleontologist and educator Stephen Jay Gould, who argued that science and religion are two “magisteria that do not overlap.” In other words, they’re perfectly compatible. “That would be true if religions claimed that the protagonists of their myths were fictional characters,” says Frías. “But what they say is that they create, destroy, transform and interact with the world. And that is where they clash with science.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.