Zohran, Barack, Kamala and Pete

The discourse of the future mayor of New York, the son of socialist immigrants, owes much to the political influence and intellectual work of his parents — just as was the case with other Democratic leaders in the past

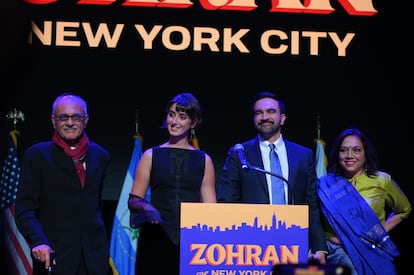

Zohran Mamdani — a 34-year-old with a degree in African Studies, born in Kampala, the capital of Uganda — will be the next mayor of New York City. He will do so after winning more than 50% of the vote, a remarkable feat. And the list of historic firsts he represents for New York’s mayoralty is long: he will be the first Muslim, the first socialist, and the youngest person to hold the office in more than a century. Yet, despite these firsts, Mamdani also embodies a certain continuity with a lesser-discussed feature of the Democratic Party in recent years: like Barack Obama, Kamala Harris, and Pete Buttigieg, Mamdani is the child of socialist immigrants.

The socialism of these parents was forged during the revolutionary decades of the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1960s, Obama’s father held a senior position in Kenya’s Ministry of Economics, serving as a self-critical socialist within the economic project led by the charismatic hero of independent Kenya, Tom Mboya. Around the same time, amid the civil rights movement in the United States, Harris’s parents met at a rally of the Afro-American Association. Both went on to earn doctorates: her mother in endocrinology — channeling her political fervor into advancing breast cancer research — and her father in economics, studying to what extent the anti-colonial politics of his native Jamaica could be applied to his adopted country, the United States.

As for Buttigieg’s father, he became the leading philologist of Antonio Gramsci’s work. Even in 2018, when I met him for the first and last time, his constellation of references for understanding contemporary politics was still rooted in the Italy of Pier Paolo Pasolini, autonomism, and the Fiat factory protests.

Mamdani’s parents share a similar political trajectory. His father, a Ugandan like him, arrived in the United States in 1963 on a scholarship for students from East Africa. As a student, he took part in north–south trips organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He later channeled that activism into an academic career focused on the analysis of colonialism, postcolonialism, and minority groups in Africa.

His mother, born in India, developed her political awareness in the street theater of Delhi. Upon arriving in the United States as a student, she also became a filmmaker, directing films that subtly challenged Hollywood prejudices: screenplays shot in foreign working-class neighborhoods, romantic comedies set against historical political backdrops, and casts without white actors.

Unlike other Democrats with socialist parents, Mamdani has not tried to distance himself from his parents’ legacy. Every move he makes on the political chessboard alludes to family politics. His activism against the siege of Gaza — whose importance to his political career has been compared to the role that opposition to the Iraq War played in Obama’s — is directly tied to his father’s anti-colonial critique. His proposals for free childcare, rent freezes, and municipally owned supermarkets echo the many domestic tensions over money that appear in Salaam Bombay!, Mississippi Masala, Monsoon Wedding, and other films by his mother.

To his detractors, all this might sound like the plot of a Houellebecq novel: a charismatic young Muslim politician, a Trojan horse deceiving well-meaning voters, a society unwittingly sliding into decline. But in reality, what it signals is an attempt to build a new coalition that brings together the young, immigrants, workers, debtors, Muslims, students, tenants, and parents — a rainbow coalition that leaves no one behind. Except the billionaires.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.