Inside a Ghanaian prison, where inmates are crammed together and close contact spreads skin diseases: ‘Everything hurts; you can’t move all night’

Overcrowding at Kumasi Central Prison has turned it into a laboratory for treating neglected tropical diseases. The lack of space and the humidity create a perfect breeding ground for tuberculosis, measles and scabies, which prisoners spread upon their release

The “cell parent” (a senior prisoner who is given some mediation tasks) and one of the high-ranking guards give the order. Of the inmates sitting on the floor, 11 lie down, with heads resting alongside feet. This is how 60 human beings manage to fit into the meager 376 square feet available in one of the cells at Kumasi Central Prison, in Ghana. Other inmates watch them silently from the three-story bunk beds. The vast majority of them slept on the floor for years, before being able to have one of the 30 beds.

The only sounds are the whirring of the fans — overwhelmed by the September heat — and the click of a camera. It captures a stark reality that, at least in this prison, the administration seems intent on “resetting.” The process begins with openly displaying what’s going on.

It’s no coincidence that these 11 prisoners are chosen: their bodies — emaciated largely because they only eat twice a day — are able to be crammed between the legs of the bunk beds. “Everything hurts; you can’t move all night,” one of the inmates laments. The men are constantly forced into close quarters, which raises concerns about the spread of disease. In the cells of Block A — reserved for convicts serving sentences of up to 10 years — a large blue jerrycan of drinking water and the toilet (camouflaged in a corner) also compete for space. In the cells of Block B — which houses those with longer sentences — the toilet sits in the middle of the room, like the throne of a king of who knows what. A television, blaring at full volume, entertains some of the dozen or so prisoners: it’s showing a soap opera starring Ruth Kadiri, a muse of Nollywood, the Nigerian film industry.

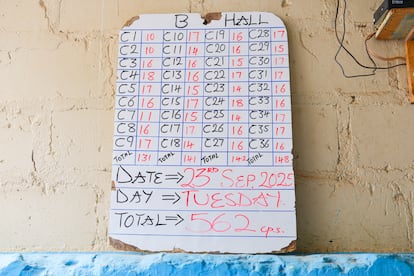

The figures for prison overcrowding in Ghana are as shocking as the photos. Back in 2014, they were the subject of a scathing U.N. report. As of this past August, the average occupancy rate across the country’s 43 prisons was 137%. When Kumasi Central Prison opened its doors to EL PAÍS on September 23, the rate here was 157%.

In this prison — founded in 1901, with space for 600 prisoners — the inmate count is kept manually on large boards. The number fluctuates drastically every day, due to a judicial system that’s as overwhelmed as the cells. On September 23, there were 1,536 inmates, including convicts, those awaiting trial, or those awaiting sentencing. Some days, the number approaches 1,900.

“The biggest challenge is overcrowding,” James B. Mwinyelle acknowledges. An official with the Ghana Prison Service, he’s the commander responsible for the Ashanti region. He has held the position since 2023. He arrived at the prison after 15 years of overseas service, on the verge of retirement, bringing with him a desire for change.

“The Ghanaian judicial system needs a breath of fresh air: fewer bars and more justice,” adds Jonathan Osei Owusu, a human rights activist and director of the POS Foundation, which works to improve prison conditions in Ghana.

As in the rest of Africa, most prisons in Ghana are converted colonial forts, where the lack of space, ventilation and hygiene results in a humid and overcrowded environment. This is detrimental to health: it creates a breeding ground for tuberculosis, measles, scabies and other neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). These spread rapidly, affecting inmates, guards and their families, both physically and mentally.

Overcrowding is also harmful to society: aside from the humanitarian crisis, it’s physically impossible to keep those convicted of crimes — like murder or robbery — completely separate from those awaiting trial. The latter, however, do sleep in a separate area (Block C) and wear hand-sewn white shirts labeled “pretrial.”

Many NTDs — such as yaws — are endemic in Ghana, making its prisons ticking time bombs. If left untreated, these diseases can lead to malformations, vision loss, organ damage and scarring. “We’ve been studying [NTDs] for 20 years, but we’ve never comprehensively examined how they affect the prison population,” Dr. Yaw A. Amoako explains, from the Kumasi Center for Collaborative Research in Tropical Medicine (KCCR). He leads the Skin Health Education Program (SHEPP), a groundbreaking project in Africa that aims to improve the management of these diseases. The Anesvad Foundation — which collaborated on this EL PAÍS report through its RESILIENTD program and the Leprosy Research Initiative — is also involved.

“We call them ‘neglected diseases’ because there are no resources to support treatment or confirm the diagnosis, [while] awareness about them is low,” Dr. Amoako continues.

These are conditions that also disproportionately affect the most vulnerable (one billion people worldwide). To eradicate them — one of the goals of the U.N.’s 2030 Agenda — it’s necessary to reach all areas where they’re still present.

The closure of USAID has been devastating: it cut short 19 years of strategy to combat these diseases. This had involved the distribution of millions of medications each year. The SHEPP program began in early-2025, with the aim of facilitating early detection and treatment of potential cases. Its success could lead to a complete overhaul of how health and carceral policies interact in Ghana. “In many cases, prisoners arrive already sick, or return to their communities sick. Imagine the consequences of a welcome party,” Dr. Amaoka sighs. “The goal is to fight disease in the prison, so as to stop its spread.”

Ghana’s prisons passed the overwhelming challenge of COVID-19: Mwinyelle claims that, thanks to “divine intervention,” not a single case was diagnosed. However, there have been other outbreaks in Kumasi Central Prison. The last serious one — which occurred just over a year ago — was conjunctivitis. Thanks to the help of local organizations, eye medication was obtained for the 300 affected individuals. The prison’s infirmary — staffed by a doctor and a few assistants, with no direct connection to the national healthcare system — is equipped to handle a limited number of cases. Back in September, it was overcrowded (like the rest of the prison). Of the 13 inmates receiving care, only four had a bed, while the rest slept on mats. “There’s a major disconnect between the healthcare and prison systems,” both the doctor and the POS leader concur.

There’s a small isolation unit used, for example, in cases of tuberculosis. Officer Eissen — who is in charge of the infirmary — explains that the most severe cases require patients to be transferred to the nearby Kongo Anokye Teaching Hospital. The annual healthcare bill amounts to 300,000 cedis (approximately $27,000), far exceeding the 40,000 cedis ($3,600) that — according to Mwinyelle — Kumasi Central Prison receives annually as an operating budget. The commander explains that, in many cases, money is requested from the prisoners themselves, or from their families, to cover the costs of treatment. Most personal hygiene products come by way of donations.

"Prison overcrowding is a key problem in neglected diseases"

“Prison overcrowding is a key problem in the fight against neglected tropical diseases. If you look at yaws or scabies, for example, they’re transmitted through direct skin contact. Ideally, the affected person should be isolated… but in Kumasi Central Prison, the space allocated for this is insufficient,” explains Dr. Yaw A. Amoako, the lead clinician at the Kumasi Center for Collaborative Research in Tropical Medicine (KCCR), who oversees the neglected skin disease project in the prison. “Furthermore, for example, with scabies – when a case is diagnosed – all of [a prisoner’s] contacts have to be examined and treated. If resources are limited for one person, imagine the impact of an outbreak in a cell with about 100 people forced to stay together,” he adds.

Providing proper care for patients doesn’t just drain the prison’s finances: it also puts a strain on the staff. Numbering about 400, they receive insufficient support and feel vulnerable to illness. The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) recommends at least 43 square feet per person in shared cells, along with a ratio of one guard to four inmates. Neither standard is being met. Meanwhile, the system for guarding a prisoner hospitalized in the infirmary involves escort shifts and Commander Mwinyelle admits that, on occasion, they do not have the resources to carry it out.

Diagnosing neglected tropical diseases isn’t simple, while suffering from them also carries significant stigma. This is according to Ruth D. Tuwor, a doctoral candidate in Sociology. She has one of the most important roles within the program: understanding and mapping the internal dynamics of the prison community. For example, in a country as religious as this one (70% of Ghanaians identify as Christian and 20% as Muslim) — and with such a large rural population — a magical interpretation of these illnesses still persists.

“People resort to traditional ointments because they think these are minor ailments. There’s also a fear of appearing sick to others,” Tuwor explains. One of her tasks is to initiate dialogue with the prisoners and staff to understand their perspectives. “You don’t want to be associated with people who are sick,” one of the inmates acknowledges. A 49-year-old man, he’s dressed in his immaculate “cell parent” uniform. This is a key position in the penitentiary’s operation: certain inmates are entrusted with day-to-day management tasks, while often mediating minor conflicts. “Many times, [a prisoner will] invent arguments to ask to change sleeping spots, so they can avoid being next to a cellmate who has a rash,” he explains. Convicted of homicide, he’s been serving his sentence since 1998.

Sometimes, it “rains” inside the cells, especially at night. This is how prisoners refer to the drops that fall from the condensation of their sweat. Part of the prison landscape consists of piles of mattresses and clothes drying outdoors. Under these conditions, inmates are prone to severe dermatitis, including eczema. These inflammations usually aren’t serious, but they can mask cases of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

“A small patch [which is a symptom of leprosy] might appear, but since it doesn’t impact your life, you see it as normal, or you ignore it. By the time you do pay attention, it’s too late, and the hospital sometimes lacks the necessary diagnostic tools,” Amoako explains. While cases of scabies can be diagnosed more clearly, the kits for testing for yaws and Buruli ulcer aren’t always readily available.

“One day, a lump appeared on my arm. It didn’t hurt, but my cellmates laughed at me. I felt ashamed. If they saw me scratching it, they rejected me. They started saying I smelled,” recalls another inmate, who asks to remain anonymous. “I found myself apologizing and afraid of dying, all because of something that wasn’t my fault,” he tells some other inmates who are part of a discussion group.

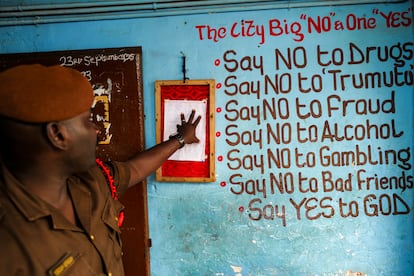

As with the cell parent, his extreme neatness is striking. How is a perfectly-ironed shirt possible in a prison? “There’s an iron in the church,” Tuwor points out. “And, in addition to that church, there’s a mosque. Religion is fundamental here.” In one of the cells in Block A, a large sign reads: “God is powerful.”

Indeed, the corridor between the two places of worship seems to be the social heart of Ghana’s largest medium-security prison. The percussive drumming emanating from the church provides the soundtrack to a kind of bustling market: it’s a frenetic coming and going, where inmates (at least, those authorized for good behavior) can sell food brought from outside, while others queue up to make phone calls to their loved ones.

Curious yet profoundly sad eyes follow the group visiting the facilities. “This will be a secure area, but it doesn’t have to be a secret place,” the warden argues. He insists that the punitive approach is a thing of the past, emphasizing the value of job training and reintegration programs. The last riot occurred in 2015.

There are textile workshops — where the incarcerated men make the uniforms and distinctive arm bands for each team of guards — and a leather workshop, where they produce sandals. Several inmates can be seen patiently threading beads to make jewelry, or working on rustic looms to produce beautiful kente cloth.

Mwinyelle hopes that, soon, in collaboration with the City Council, a shop can be opened in Kumasi, to sell these products. The current training program — which includes basic education — also covers carpentry. And many prisoners also volunteer in places like the kitchen.

Watery bean soup

At Kumasi Central Prison, meals are served twice a day, from metal plates that are as cold as they are cruelly practical. In the mornings, porridge cooked over a wood fire is served. And, for dinner — served at 1 p.m. — there’s a very watery bean soup and a portion of banku, a bread made from fermented corn and cassava dough.

At the end of September, the Ghanaian government increased the daily ration allowance for the first time in 15 years: from 1.8 cedis (14 cents) to five cedis (40 cents). The World Bank estimates that Ghana’s GDP per capita last year was $2,265, 15 times lower than a country like Spain.

According to the World Prison Brief — an online database published by the Institute For Crime & Justice Policy Research (ICPR) — Ghana’s prisons held a total of 14,133 inmates this past August, or 41 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants. This rate is almost 10 percentage points below the average for West African countries (50) and five times lower than the rate in southern Africa. This favorable position, however, clashes with the fact that jails are overcrowded, which is why there’s been a focus on prison conditions.

Commander Mwinyelle — supporting the idea of ”resetting” the country, which has been championed by President John Dramani Mahama — advocates for a farm-like model of prisons, where better sanitary conditions can be guaranteed and, for example, the impact of NTDs can be mitigated. This is one of the ideas that the National Prison Service is attempting to implement.

The commander acknowledges that these longer-term plans — such as relocating the prison away from the center of Ghana’s second-largest city — are always threatened with being derailed by bureaucracy or a change in government. Other initiatives — supported by human rights groups — have been more successful, with tangible effects on reducing overcrowding. One example is the Justice for All Program (JFAP), run by the POS Foundation. Since 2007, it has been instrumental in reducing the total number of pretrial detainees from 33% to 10%. “[The organization set up] mobile courts that visited prisons to provide on-site legal assistance to pretrial detainees, many of whom had been waiting to go to trial for years,” explains Jonathan Osei Owusu, executive director of the POS Foundation. The initiative has been recognized by the U.N. and is being implemented in Kenya, which has a severe overcrowding problem, with a prison occupancy rate of 195%.

The program has since evolved. It now also works to review excessive sentences and provide general legal advice through volunteer lawyers, or even via prisoners who have been trained for this purpose. With a population of 33.5 million, Osei Owusu points out that Ghana has only 55 public defenders. In Spain, last year, there were about 39,941, according to data from the General Council of Lawyers.

Both the director of POS and the commander of Kumasi Central Prison agree on the need to amend certain laws and develop new regulations to alleviate the backlog. “It makes no sense that someone who steals something worth 100 cedis [about $9] should share a cell with a murderer,” the activist sighs. Owuso is waiting for the government to approve a bill that would commute sentences of less than five years in prison to community service.

The change of government in Ghana last December halted the legislative process for the law on parole. It also stalled the regulations that would allow drug addiction to be treated as a public health issue, rather than as a criminal matter. Another issue awaiting codification is the legal vacuum regarding the length of pretrial detention, which in Spain is 72 hours, but is indefinite in Ghana. “For one judge, two years might be reasonable; for another, five. This ambiguity destroys lives,” Owusu laments.

“The judicial system, the police, the prisons and the healthcare system function like disconnected parts of the same broken machine,” the director of the POS Foundation summarizes. Nevertheless, he sees some progress after a decade of the U.N. reprimanding Ghana. For example, there’s new openness to conducting studies like the one led by Dr. Amoako.

Still, the pace of reforms seems to be the same as the passage of time in Kumasi Central Prison. Things are moving slowly, with difficulty, like the blades of the fans that try to alleviate the stifling heat in the cells. Most of these secondhand machines are the main items that get fixed in the electrical repair workshop, where prisoners receive training. The room designated for classes is small and smells of grease and short circuits, but this doesn’t discourage the handful of inmates, who are paying careful attention to the wires scattered across the table. Here — and throughout the country — there is, at least, a desire to try to fix things.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition