Journey to the heart of kush, the drug devastating West Africa

A lethal mix of cannabis and synthetic opioids up to 25 times more potent than fentanyl is causing dozens of deaths and has become a public health emergency in countries like Liberia and Sierra Leone

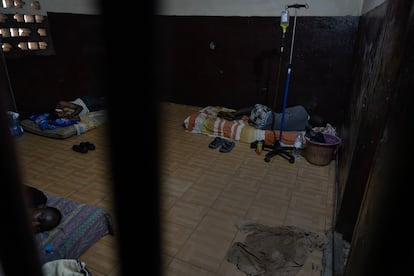

The room smells of sweat and fear. A thick chain with a padlock seals the barred door, and inside, three young people lie on mattresses on the floor, dozing off thanks to a mix of exhaustion and diazepam. Every so often, nurse Saio Keita approaches to check their vital signs, and the youths stir in their half-sleep. Ibrahima (a fictitious name) is one of them. Connected to an IV drip, he watches her expressionlessly and dazed from somewhere deep within his mind.

The three are users of kush, the dangerous drug currently in vogue in West Africa, that is made of cannabinoids and synthetic opioids up to 25 times stronger than fentanyl. Since its emergence in the region three years ago, it has become a deadly plague that has even prompted Liberia and Sierra Leone to declare a public health emergency.

You have to know exactly where it is to find it. After going down a pothole-filled dirt road and crossing a small open lot in the Dabompa neighborhood on the outskirts of Conakry, you reach the Sajed center for drug treatment. It is one of the few institutions offering help to people using substances such as crack, cannabis, or cocaine in Guinea-Conakry. However, in recent months, kush has taken hold with alarming speed.

“It is very destructive and dangerous, and we are seeing its consequences every day, with frequent cases ending in death,” says Dr. Marie Koumbassa, who runs the facility. “It’s the drug of the moment.”

Kush first appeared in Sierra Leone in 2022, according to a recent report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, and since then it has rapidly spread to neighboring countries such as Guinea-Conakry, Liberia, Guinea-Bissau, Gambia, and Senegal, representing a major shift in regional drug use.

“The scale of its market expansion and its lethal public health effects are unparalleled,” the report notes. In Sierra Leone and Liberia, a national public health emergency has been declared due to the high number of fatalities. “Mass fatalities overwhelming mortuary systems, forcing emergency group cremations, and leading to bodies being abandoned in the streets,” the study states.

Kush is an aggressive and constantly evolving mix of substances, including powerful nitazene opioids and synthetic cannabinoids, smoked in the same way as marijuana or hashish. “We have seen it combined with acetone, formaldehyde, cannabis, amphetamines, tramadol, or fentanyl, and it creates a high level of dependence,” says Dr. Koumbassa.

At the center she runs, the first thing they do with patients is a urine test to measure hemoglobin. Users often arrive in the middle of a crisis, so they are given a combination of sedatives and vitamins intravenously. “They experience headaches, vomiting, seizures, fever, and are sometimes very aggressive. We are forced to use restraint methods,” she adds. Antipsychotics and anxiolytics are also used, depending on the case.

In Kolabouy, a crossroads in the north of the country, a group of young people openly smoke kush. “They don’t do anything all day,” says Mariama, a resident, “this drug makes them numb.” A few days after entering the Sajed center, Ibrahima feels recovered. “Bad decisions brought me here; I’ve lost interest in everything, and this is the only thing that gives me a break. I used to smoke crack, but kush makes me completely forget about my problems; it’s a death trap because it makes you lose even your family. They don’t want anything to do with me. This substance is loved and hated at the same time,” he explains, distressed.

The latest report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), presented in Bamako last June, already warned about the emergence of kush and the enormous harm it causes, as well as about West Africa becoming one of the main transit points for cocaine to Europe and the increase in its consumption in the region.

“Cocaine is mostly used by middle-class people, while kush is more the drug of the poor,” says Dr. Koumbassa. In Dakar, Senegal’s capital, a dose can be found on the street for less than a dollar, and dealers abound in areas popular with young people. According to a survey by UNODC and the government of Guinea-Conakry, 1% of students ages 15 to 18 report having used it, making it the third most widely used drug in this age group after cannabis and inhalants such as glue.

The ingredients for kush come from China, the Netherlands, and probably the United Kingdom, according to research conducted by the Global Initiative, and reach Sierra Leone, the main producing country, via postal services and maritime routes.

A study led by Professors Michael Lahai and Ahmed Vandy from the School of Pharmacy at the University of Freetown even claimed that, on some occasions, human bone powder is added to the mixture because of its high sulfur content, which enhances its effects. Traffickers have been arrested for digging up corpses in the country’s cemeteries.

In 2023, 59% of the patients admitted to the country’s only psychiatric hospital had used kush. Initially controlled by a few criminal groups, its production and distribution have since become fragmented, complicating efforts to combat these networks.

In Conakry, Yamoussa Bangoura, head of psychotherapy at the Sajed center, complains about the lack of resources to treat people addicted to this substance. “Since 2019 we have treated over 500 patients, but we lack everything — medication, staff, and resources to go where the problem is,” he says.

The center, with the capacity to house 16 people across three rooms — one for women and two for men — also has a laboratory, a TV room, and a kitchen. They receive funding from private donors, generally small amounts, which allow them to continue their work, but they hope to create two new facilities, one in Boké and another in Guinée forestière. In these two remote border regions, kush runs rampant.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.