‘Maps are not innocent drawings’: Africa demands its true size be shown

The African Union is pushing to end Mercator’s distortions and replace it with projections that reflect the continent’s real proportions

“A map is not just a technical tool, but a symbol, and symbols matter. For us, correcting the map also means correcting the global narrative about Africa,” says Fara Ndiaye, co-founder and deputy executive director of Speak Up Africa, one of the organizations behind Correct the Map. The African Union (AU) has just endorsed this initiative, which seeks to force governments, international organizations, and educational organizations to stop using the Mercator world map in favor of one that more accurately shows the size of Africa, which is minimized in the classic projection.

“It might seem to be just a map, but in reality, it is not,” AU Commission deputy chairperson Selma Malika Haddadi told Reuters, saying the Mercator fostered the false impression that Africa was “marginal,” despite being the world’s second-largest continent by land area.

Ndiaye believes this endorsement is a historic achievement that sends a powerful political message. “It’s the first time a pan-African institution has taken a clear position on the visual representation of Africa,” he explains in a video call with EL PAÍS, adding that this support transforms what was initially “a cultural and civic demand into a continental policy aimed at the entire world.”

For Carlos Lopes, a professor at the University of Cape Town and a contributor to Africa No Filter, the other organization behind the initiative, AU’s support is “a sign that Africa refuses to remain a footnote in its own history.” In an email exchange, the academic says that this isn’t just a cartographic debate, but rather one about “dignity, education, and even diplomacy.” “After all, if your house always appeared tiny on Google Maps, you’d end up wanting it corrected,” he adds.

Although these criticisms of the Mercator map are not new, the campaign has reignited the debate at a moment of postcolonial rupture and reaffirmation of African identity. Lopes believes the persistence of these distortions has to do with the fact that, “once a worldview takes root, it becomes very comfortable.”

However, he believes that “maps are not innocent drawings,” but rather shape how we see ourselves and others: “If Africa appears smaller than it is [in relation to other continents], so does its weight in the imagination of citizens and decision-makers. Correcting the map is not vanity: it is reclaiming reality.”

“Incorrect maps undermine the capacity for action”

In 1569, the Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator decided that a new kind of map was needed for navigation. Because the Earth is spherical, if you drew a straight line on a map to travel, for example, from Seville to Cuba, you would end up off course, explains British historian Jerry Brotton, author of A History of the World in 12 Maps.

His solution was a projection that inevitably creates distortion: the farther north or south you go, the greater the distortion. “He wasn’t deliberately minimizing the size of Africa,” says Brotton, adding that Mercator designed it to aid east–west navigation.

“When you look at polar regions like Siberia, northern Canada, or Greenland, they appear greatly magnified. I ask my students to compare the size of Greenland and Africa. In the Mercator projection, the two landmasses appear the same size. However, in reality, Greenland is 14 times smaller,” explains cartographer Bernhard Jenny, a professor at Monash University and co-creator of the Equal Earth projection.

“This is the map we’ve primarily seen since the 16th century. But I think it’s important to note that it had a specific purpose, maritime navigation, not to represent the continents equally. The world has evolved enormously in recent centuries. And it’s important that we make sure we update the tools to reflect reality,” Ndiaye explains.

Lopes agrees: “Children learn from these maps. They grow up thinking Africa is modest in size when, in reality, it’s gigantic: larger than the U.S., China, India, Japan, and much of Europe combined. Perception translates into confidence, and confidence into action. So yes, inaccurate maps undermine the capacity for action.”

“We also know that this distortion has geopolitical consequences, as maps reinforce the perception of which regions are central and powerful and which are peripheral,” adds Ndiaye. “By adopting these fair representations in schools, the media, and international organizations outside of Africa, we contribute to breaking down these outdated hierarchies and promoting a more balanced world.”

The Mercator projection is still used in tech companies, institutions, and schools, though changes are gradually taking place. In 2018, Google Maps replaced it with a 3D globe on its desktop version, although users can switch back to Mercator if they prefer. The cell phone app still defaults to Mercator. Institutions such as NASA have used projections like Equal Earth for climate maps, and a World Bank spokesperson confirmed to Reuters that they now use Winkel-Tripel or Equal Earth for static maps, gradually phasing out Mercator on web maps.

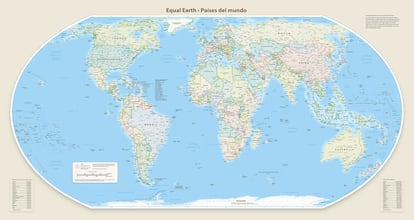

The campaign recommends the Equal Earth projection, created in 2018 by Bernhard Jenny, Tom Patterson, and Bojan Šavrič. “We asked ourselves, ‘How is it possible that people still seriously use that [Mercator] map projection for world maps?’ We decided we had to do something,” Jenny recalls. With Equal Earth, its creators hope to offer an alternative to traditional projections and help people better understand how the continents are formed.

A global debate on the representation of Africa

The executive director of Speak Up Africa believes that what’s at stake is not just a change in the proportions of the world map. “Showing Africa in its true size reinforces pride and confidence among Africans, especially among the younger generation. And that’s why I think it’s also important that the campaign’s first audience be Africans,” explains Ndiaye, adding that change must come from within the continent: “When we know exactly who we are and what we stand for in the world, that will facilitate our relationships with others.”

However, she argues that correcting the map is not only an African issue; this more accurate construction of the world concerns everyone: “When non-Africans grow up learning from distorted maps, they develop the mistaken perception that Africa is smaller and less significant than it really is.”

The campaign hopes that African Ministries of Education, especially following support from the African Union, will adopt the Equal Earth projection in school curricula. It also advocates for African and international media to use more accurate maps in their publications. The campaign wants to spark a global debate on how Africa is represented in education systems, narratives, and the collective imagination.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.