Lota de Macedo, the Brazilian visionary determined to build a ‘Central Park on the sea’ in Rio de Janeiro

The self-taught urban planner fought pressure from politicians and real estate interests to build Flamengo Park, which just celebrated its 60th anniversary

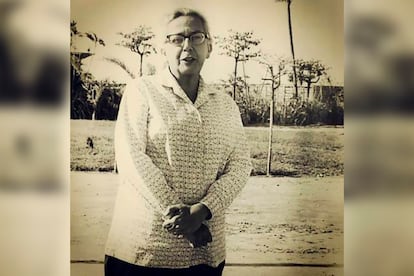

A new green, leafy lung for Rio de Janeiro, built on a massive outcropping of land claimed back from the sea. Such was the ambitious idea on the mind of Carlota de Macedo Soares (1910-1967). Better known as Lota, she was a tenacious Brazilian woman who fought against all odds to achieve her dream of building a park for the people. This month, Flamengo Park celebrates 60 years of verdant beauty. The story of its creation is a Carioca epic full of twists and turns, much like de Macedo’s own personal life, which was marked by her stormy relationship with the American poet Elizabeth Bishop.

At first glance, it seems as if Flamengo Park has always been there, with its bright green grass, tropical trees near Sugarloaf Mountain, Rio’s iconic landmark that can be seen from all vantage points in the city. But 60 years ago, the area was covered by the ocean. The park’s 120 hectares of green space were, in fact, created from the rocks, rubble and sand generated by the demolition of a hill in the city’s center, and the construction of the tunnels that were then just beginning to be drilled through the city’s trademark surrounding granite hills. In fact, Cariocas simply call the park aterro, meaning “land on sea.”

By this time, Rio had lost its capital status to Brasilia, but it did not want to be beat in the race for modernity. The car was seen as the passport to progress, and a huge esplanade was needed to build highways between the city’s center and its booming new neighborhoods in the south, like Ipanema and Copacabana.

The governor of the newly created state of Guanabara, (which was named after the bay on which Rio is perched) Carlos Lacerda, asked de Macedo, a close friend, to decide what to do with this huge expanse of land. Lota proposed reducing a previous plan to build four highways down to two, saving the rest of the space to construct a tropical Central Park by the sea.

She created a working group and installed the very best in its leadership positions. It was a largely male clique, from which two names stand out: that of modernist architect Affonso Eduardo Reidy, who headed the site’s urban planning, and Roberto Burle Marx, entrusted with the construction of the gardens.

Rio already had considerable green space in the elevated region of the city, the Tijuca jungle, but it had historically functioned as a hidden-away space for the bourgeoisie’s al fresco picnics. The city lacked a grand, street-level park for the masses, where workers could enjoy their Sundays with dignity.

In addition to green spaces, the team planned museums, open-air auditoriums, a puppet theater, and a runway for model airplanes. “It is an urgent and unprecedented project: it cares as much for the beauty and conservation of the landscape as for its usefulness. It puts human needs before the demands of machines, it dares to offer pedestrians, the outcasts of the modern age, their share of peace and leisure,” commented de Macedo in a 1964 article published during the final stages of the park’s construction.

De Macedo was raised in a high-society family, attended the best schools in Paris and Switzerland, and studied painting with Candido Portinari. What she did not have was a university degree, but she had an abundant amount of tenacity and a very clear idea of what she wanted. This came in handy, as there was constant in-fighting within her working group, an abundance of ego clashes, says Claudio Machado, vice president of the Lota Institute, which was created by the woman’s fans to preserve her memory.

Burle Marx went so far as to call de Macedo arrogant and authoritarian in newspaper interviews. “She was a woman without a degree bossing around a bunch of men, and on top of that, she was a lesbian,” says Machado in a café located next to the park. “She was everything that society at the time did not accept. But she was very incisive, she was afraid of nothing.”

It was de Macedo who served as the bridge between the project’s designers and the political world. Her friendship with Governor Lacerda and her powers of persuasion were key to saving the project from pressure from the real estate sector, whose leaders dreamed of filling the prime waterfront land with buildings.

Concerned about the future of the park, de Macedo managed to have the project declared a protected heritage site before it even opened. She also insisted on creating a foundation to manage the green space, to keep it safe from political interests. Its construction was a headache, but also provided room for pleasant surprises.

On one occasion, de Macedo took advantage of the fact that Lacerda was on an official trip outside Brazil in order to take the project a bit further than originally intended. She already had a dredger on hand that extracted sand from the seabed, and didn’t hesitate to improvise a new beach in Botafogo Cove. Upon his return, the governor was furious that the project’s funds had been exhausted, but quickly reconsidered when he saw the joy of the neighborhood and the banners thanking him for his efforts.

De Macedo met a sad and premature end. When her friend Lacerda left the state government in 1965, she was removed from the management of the park shortly before it was due to be inaugurated. This, added to a long list of disappointments, plunged her into a long depression that led to a three-month hospital stay.

She spent years in a complicated love triangle involving Mary Morse, her first partner, and Bishop, whom she met later on in life. She even adopted a little girl with Morse named Monica, who would later be raised by the three women. Bishop gradually faded away from the relationship, later returning the United States.

In 1967, by which time the “landfill” park was the favorite of the Cariocas, de Macedo boarded a flight to New York to attempt to win back her poet. Their reunion went worse than expected, and the urban planner attempted to take her own life with an overdose of barbiturates. She fell into a coma and died a week later.

With no one to defend her legacy, de Macedo’s profile has faded over the years. (Another factor was her celebration of Brazil’s 1964 military coup.) What remains is the legacy of her park, a “resilient survivor,” as Fernando Nascimento, president of the Lota Institute, puts it. The institute is now planning an extensive program of events on summer Sundays to revive the park’s modernist bandstand. The Rio city council is also finalizing some minor extensions at the northern end of the park.

All these plans must be carefully plotted, because in 2012, UNESCO declared the entire green space a World Heritage Site due to its unique symbiosis of city, mountains and ocean. On Sundays, the avenues that cross Flamengo Park are closed to traffic and filled with locals walking, cycling and rollerblading. Barbecues, soccer games and colorful birthday picnics take up every corner of its expanse. Even swimming in the sea has become popular again, the waters cleaner than ever after years of intense pollution. Security, long the park’s Achilles heel, has improved in recent years, and there are more and more visitors, even at night, when it is lit up by the huge 148-foot streetlights (at the time of their construction, the tallest in the world) that de Macedo designed, inspired by the zenithal light of the moon.

This illumination is rivaled only by the Talipot palm trees planted by Burle Marx, a species native to India and Sri Lanka that only blooms once upon reaching adulthood, between the ages of 60 and 70. At that point, the trees die abruptly, leaving behind hundreds of thousands of seeds. This spring, the white tops of the flowering palms are peeking out from the green of the park, a floral reminder that the lung of Rio de Janeiro is all grown up.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.