Latin American democracy, as told by five powerful women

On the International Day of Democracy, women from the region who have attained important positions in politics and justice discuss the state of the political system and the challenges they face

This Friday is the International Day of Democracy. Five women who occupy powerful positions in politics and justice in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico tell us about how to protect these achievements, as well as the challenges they continue to face as women. We asked them all the same questions about the crisis of democracy and how a better version can be built.

How would you define the state of democracy in your country, and what is the main challenge that women face?

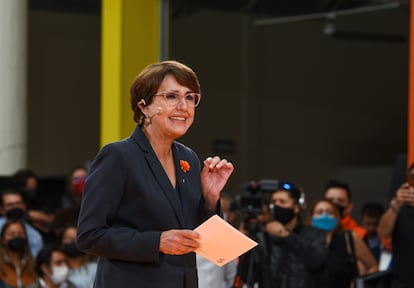

Norma Piña, chief justice of the Supreme Court of Justice of Mexico. Democracy and equality are experienced day by day, and women face specific challenges in that regard. When we think about patriarchy, we can see similarities with the attacks on democracy that our region is facing: both have been able to adapt to social changes in order to preserve power in the hands of the few. Unfortunately, inequality has been perpetuated in our daily lives, and it isn’t questioned much.

[We live in a] State where women continue to live in fear, facing daily violence that puts their lives at risk or [kills] them; where [gender] roles and stereotypes render invisible their fundamental participation in daily life, such as carework, without which society would not exist and which is primarily carried out by women. [That work] continues to fall to them. The playing field is not level for women, as each step and gain [that moves us] toward equality costs us disproportionately and unnecessarily. Such a State cannot represent itself as democratic or believe that it is democratic.

In this sense, the Mexican Supreme Court of Justice has ruled that, in order to guarantee effective access to justice for women, girls and adolescents, it must always be judged from a gender perspective, that is, based on a recognition of the differentiated impacts that a woman may be experiencing in each case because of the fact that she is a woman. Justice without a gender perspective cannot be called justice. When inequality and gender-based violence persist, democracy cannot be called democracy. Violence against women and gender-based inequality are the opposite of a democratic state governed by the rule of law. It’s that simple.

Carolina Giraldo, congresswoman from Colombia and president of the Women’s Equality Commission. We must build a more egalitarian democracy. More women means more democracy, because we emphasize an agenda of opportunities, public health, environmental care, non-discrimination. Although the number of women and diverse people in politics has increased, we still see a significant gap in decision-making positions, [which are] traditionally led by men. A more equitable democracy would allow for social transformation and changes in public policy.

Once we reach those spaces, it’s crucial that participation is substantive and not a simulation in which our voices continue to be ignored. That implies confronting one of the strongest—and falsest—roots of the patriarchal system: [the notion] that men—and only certain types of men—are the only ones who can make decisions and occupy public space.

For women, the challenge of gender-based violence persists. The femicide and sexual violence numbers are alarming. Another challenge for women and LGBTIQ+ people, particularly for those who participate in politics, is to stop being considered [part of] a gender quota and [instead] demand the development of strategies that promote political participation and the inclusion of women and LGBTIQ+ people in public life. In Colombia there is a 30% “gender quota” in public corporations. The country has progressed toward parity in spaces such as boards of directors, but parity has still not been achieved in building [the leadership] of public corporations.

Patricia Mercado,a Movimiento Ciudadano [Citizen Movement] senator in Mexico and a 2006 presidential candidate. The greatest challenge facing Latin American democracies is the profound inequality. Certain leaders take advantage of the disenchantment of millions of people to attack and dismantle democratic institutions. That is why we should prioritize building welfare states that guarantee the promised equality of opportunities.

Democracy has not been consolidated in Mexico. Divided governments have been a positive experience for creating agreements amid differences. For example, over the past 27 years, at least political-electoral reforms have been adopted by general consensus. At present, there is a pause in this process of democratic consolidation, amid an abundance of actions against the division of powers, against autonomous bodies and against the separation between public office and party politics.

Erika Hilton, Brazilian trans legislator. She is one of the first two in her country’s history. In the past four years, Brazil has undergone a challenging major democratic crisis, with numerous attempts to break with the democratic rule of law, particularly the coup attempt on January 8, 2023.

With the election of President Lula [da Silva], we have now managed to stop the process of democratic deterioration that was underway under Jair Bolsonaro, but there’s a long way to go to change course after so many attacks and so much anti-democratic ideological propaganda.

For social minority [groups], such as women, LGBTQI+, blacks, indigenous people, the fight is even more arduous, since these populations never had full democracy [in the first place], [they’ve been] victims of violence, prejudice and a lack of public policies. Concretely, I believe that our challenges are breaking this historical cycle of compulsory marginalization, the lack of basic rights and achieving the [full] realization of our citizenship. Increasing our political representation is fundamental, but grassroots organization will be the key to fighting in defense of our rights in the public sphere.

Silvia Lospennato, a Juntos por el Cambio [Together for Change] bloc representative in Argentina’s national congress. In Argentina, in the coming months, we’ll be celebrating 40 years of democracy, a long period of political stability and unrestricted respect for human rights. This political stability has not been accompanied by the same level of economic stability, because in the past 40 years we have undergone major economic crises, and their social consequences have deteriorated the quality of life of millions of Argentines. However, even in the most dire moments, democratic institutions were central to addressing the crises within the framework of the National Constitution.

During that time, there have also been enormous advances in recognizing the rights of women and diverse groups, which are the result of this democratic pact. Many of these rights were guaranteed through laws that not only had a broad consensus at the time they were enacted, but they were also accompanied by public policies to ensure access to these rights. At present, the economic and social crisis that Argentina is experiencing has increased [people’s] levels of dissatisfaction with democracy. That [sentiment] is reflected in polls, especially among young people, and of course that is a cause for concern. However, I am optimistic about the resilience of our democratic commitment, [its ability] to persist and defend all the rights that have been gained over the years.

What must be done to improve the representation and participation of women and LGBTIQ+ people in spaces of power?

Norma Piña. One of the most representative achievements of the movement of women and LGBTIQ+ people is occupying positions of power. It’s been a long road, but the general results have been good. In Mexico, parity has been building since 1997, and it wasn’t until 2019 that we achieved so-called “parity in everything” at the constitutional level…Until the 2021 elections, political parties had to guarantee the candidacies of LGBTIQ+ people, among other groups that have historically been discriminated against, such as indigenous people, Afro-descendants and people with disabilities.

However, social reality has not yet caught up with the law. Although there are more and more women and LGBTIQ+ people in positions of power, progress has been slow; to become a reality, it requires a lot of political will, citizen action and awareness. We can see parity in Congress and even in important spaces occupied by women, such as the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs…but we’re still far from doing that across the board in all spaces.

Look at the case of Mexico’s own Supreme Court. In its almost 200 years existence, only 14 women have been officials, and the country’s highest court didn’t have its first female chief justice until 2023. Of course, that didn’t happen suddenly. I was a judge and then a magistrate. And in 2015, almost 20 years after starting my judicial career, I was chosen as a justice for the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, from a shortlist that was intentionally composed exclusively of women. Today, we have the most women on the Court in its history: 4 of its 11 members. But we still have a long way to go to achieve parity.

Carolina Giraldo. In the case of diverse people, the legislative elections of March 2022 represented a crucial milestone in the history of LGBTI+ people’s political participation in Colombia. Currently, there are seven openly diverse members of the Congress of the Republic. This is a historic fact in a country where discrimination still exists and takes lives, and in an institution where debates about the LGBTI+ population’s rights have traditionally been avoided.

We need the education system to respond to the demands of gender parity. Although gender quotas have been a strategy for increasing women’s representation in politics, they are not enough on their own. States must create spaces for discussion and the recognition of diversity in order to eliminate practices that create discrimination and prevent women and diverse people from accessing positions of influence.

Political parties and the State must promote far more schools for women’s political participation and training, as well as guarantee that political campaigns are financed with an eye to gender equity.

Patricia Mercado. Although we have managed to institute parity, which aims for equal participation between women and men, discrimination persists. The rules for promotion and advancement within [the political] parties are clear. Often, women who enter politics do not have the contact networks and alliances that men do, and they also face situations of gender-based violence that impede their political development.

[We must] establish that the State is responsible for caring for dependents. Until that happens, we will not achieve equal and equitable levels of inclusion in the labor [market] and political participation. For LGBTIQ+ people, there have been advances in the electoral institute’s guidelines for affirmative action in candidacies. That must continue and be codified in law.

Erika Hilton. [There] are several factors, but a good start [would be] for political parties to really invest in these candidacies with financial, legal [and] political support, visibility, and not just using women, black, indigenous and LGBTQI+ people as token representatives to give the illusion of diversity, where political power is still concentrated in the hands of rich white men, [who are] the heirs of decades of political dominance around the world.

Silvia Lospennato. We have guaranteed formal rights and, for women, a parity law that ensures equal participation in elected public positions and within political parties. We also have political party financing quotas that must be applied to women. However, the increase in women’s participation in parliamentary positions does not correlate with executive positions; women governors and mayors largely continue to be an exception.

The same is true of other areas of power, such as access to public companies’ boards of directors and senior positions in the judiciary. In fact, in Argentina our Supreme Court of Justice doesn’t have any women at all. This shows that quota systems continue to be a necessary tool, at least in the short term, in order to guarantee women’s participation in decision-making spaces. But power is not only exercised in the public sphere; we must also continue to fight to break glass ceilings in the labor market with public policies; [there must also be a] cultural change in the private sector to follow that path in women’s careers. In Argentina, we need a comprehensive care system that allows for reconciling family life with work, and [we have] to modify the leave system to promote co-responsibility in care, among many other steps that are essential for not only formal but substantive equality of rights.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.