‘El Mayo’ Zambada and the drug empire that benefited from corruption in Mexico: Keys to the US accusation against the Sinaloa Cartel leader

Washington claims the veteran drug lord and other cartel leaders earned $10 million a year from cocaine trafficking alone, while El Mayo held assets worth $15 billion

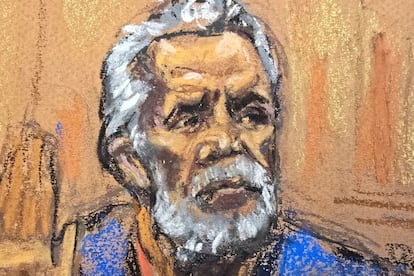

For the United States, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada was “a principal leader of a continuing criminal enterprise” known as the Sinaloa Cartel. In addition to the alias El Mayo, he was known by the nickname Doc, according to one of the several accusations filed by the U.S. Attorney’s Office against the drug lord, who pleaded guilty Monday to conspiracy and directing a drug trafficking criminal enterprise. Washington maintains that the Sinaloa Cartel had operated at least since the 1990s thanks to the corruption of Mexican police officials, politicians, and judges. Zambada himself admitted this claim in his hearing in federal court in New York, where he said that he had indeed paid bribes to security officials and politicians, although he did not name any names, nor will he, according to the drug lord’s defense team.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office alleges that El Mayo and other cartel leaders, including Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, obtained “substantial income and resources of up to $10 million gross over a 12-month period from the manufacture, importation, and distribution of cocaine” in the United States. Added to this are the multimillion-dollar profits from the smuggling of other drugs, such as marijuana, methamphetamine, and fentanyl, the Sinaloa Cartel’s specialty.

The figure recorded by the United States is just the tip of the iceberg of the veteran drug trafficker’s fortune. Judge Brian Cogan ordered the confiscation of Zambada’s assets and property totaling $15 billion (280 billion pesos). The figure is stratospheric, but it is largely explained by the fact that, according to Zambada’s own statement, he had been involved in the illicit drug trafficking business for nearly six decades, until his downfall last year, when he was handed over to Washington by Joaquín Guzmán López, one of El Chapo’s sons.

El Mayo pleaded guilty solely to charges related to his leadership of the Sinaloa Cartel, filed by prosecutors in two separate indictments, one from 2009 and the other from 2012. Those documents describe the cartel’s operations as a criminal enterprise dating back to the 1990s, when it was also known as The Mexican Federation or The Alliance, operating as “an organized crime syndicate founded on strong relationships between major drug lords, a council with representatives from the criminal organizations of its top leaders.” The 2009 indictment names El Mayo Zambada, along with brothers Arturo and Hector Beltrán-Leyva, Ignacio Nacho Coronel, El Chapo Guzmán, and Jesús Zambada, “El Rey,” El Mayo’s brother.

Filed almost 15 years ago, the indictment does not address the moment in which the alliance of legendary drug lords broke up due to mutual betrayals, nor the deaths of several of those criminal leaders (the two Beltrán-Leyvas and Nacho Coronel) or their capture (El Chapo, El Mayo, and El Rey are all in the hands of the U.S. authorities). However, it does point to how the Sinaloa Cartel exercised control over “government officials and law enforcement officers” that allowed it to operate a “large-scale narcotics transportation network involving the use of land, air, and sea transportation assets, which eventually led to the Cartel shipping multi-ton quantities of cocaine from South America, through Central America and Mexico, and finally into the United States.” The document indicates that, although the cartel leaders sometimes clashed, they prioritized the functioning of the organization, sharing trafficking routes, reducing violence, and, above all, “ensuring their political and judicial protection.”

The 2012 document adds that, under the leadership of El Mayo and El Chapo, and equipped with hitmen and groups that functioned as armed wings, the Sinaloa Cartel spearheaded the trafficking of tons of cocaine and marijuana to the United States, laundered funds, and ordered murders in both Mexico and the U.S. The criminal group, according to the indictment, kidnapped, tortured, and threatened rival drug traffickers, potential informants, security agents, journalists, and innocent bystanders, as well as disloyal members. The prosecutor’s file chronicles the Sinaloa Cartel’s alliances with the armed wing Gente Nueva and its war against the Juárez Cartel, led by Vicente Carrillo Fuentes, known as “El Viceroy”, for control of the trafficking route to the United States. According to the Prosecutor’s Office, all profits obtained in the United States “ultimately returned” to El Mayo and El Chapo in Mexico.

That money was also used by both bosses to “reinvest” in the criminal enterprise, the document adds: to purchase equipment — weapons, ammunition, bulletproof vests, radios, vehicles — and properties for the cartel’s use, but also to pay its members and associates. The document mentions the names of several municipal and state police officers from Sinaloa and Chihuahua on the cartel’s payroll and names them as co-defendants of Zambada and Guzmán.

Based on statements made Monday by El Mayo about corrupting police and military commanders, as well as politicians, it is certain that the organization’s payroll included high-ranking officials. U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi echoed these statements and asserted that the criminal leader “paid bribes to government officials,” whom she described as corrupt. In Mexico, however, these alleged accomplices can breathe easily, as the kingpin’s lawyer, Frank Pérez, has assured that his client will not cooperate in any way with U.S. justice.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.