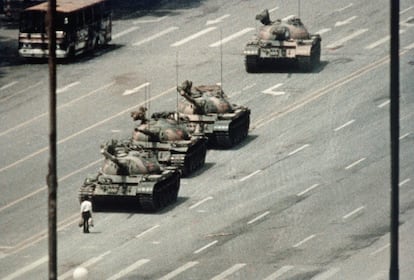

Relatives of Tiananmen victims fight against being forgotten in China: ‘I wish the government would give the people answers’

Beijing maintains official silence on the bloody 1989 crackdown, while victims’ families and activists demand justice and the truth

Mrs. You Weijie opens the door after a second knock. Her face registers surprise, but she says urgently, “Come in, come in, please.” She closes the door immediately. She apologizes because she’s still in her pajamas, having just gotten up. She makes her excuses before going to change. In the room, there’s a humble dark wooden sofa upholstered in elegant white, a small upright piano, an antique clock on the sideboard, and a lamp decorated with little birds. The walls are wallpapered with turquoise floral motifs. Mrs. You quickly returns and sits down.

It’s early Saturday, May 31. The following day, state security services will take her out of Beijing to prevent this woman, a spokesperson for the Tiananmen Mothers (the group of relatives of the victims of the student massacre that took place in the heart of the Chinese capital in 1989), from becoming the focus of any news when the anniversary arrives on June 4. This is a common practice by the authorities to silence critical voices, and one that various activists face on sensitive dates.

“It’s a very tense moment,” You says early in the interview. She avoids providing details about where she will spend the next three days. “I have to keep a low profile,” she insists. She seems to be getting flustered. She apologizes again for having just woken up. She stands and pours herself a glass of water. Her face radiates sweetness and sadness in equal measure. She is 72 years old. Her long, dyed hair reveals a little gray. “I can’t tell you. I have to be discreet, I’m sorry,” she simply explains.

Few dates are as difficult to say out loud in China as June 4. Thirty-six years after the government ordered the bloody repression of peaceful protests in Tiananmen Square that had been demanding political reforms for weeks, the event is invisible in textbooks, the media, the tightly controlled internet, and everyday conversations.

The victims lack official recognition — the total number remains unknown, with estimates ranging from hundreds to several thousand — and their families must grieve in silence, under surveillance, and with little opportunity to pay tribute. The younger generations barely know what happened, and some even doubt it really did. Beyond the country’s borders, however, some of the protesters in exile refuse to let the flame of memory go out, aware that forgetting is also a form of defeat.

Trying to speak to anyone connected with those events inside China is an increasingly complicated task. Censorship, constant surveillance, and fear of personal consequences have imposed a silence that is difficult to break. EL PAÍS was able to do so last weekend for 10 minutes.

You’s husband, Yang Minghu, was 42 years old when he was awakened by the sound of gunfire in the early hours of June 4, 1989. Alarmed by his neighbors’ testimony and concerned for the protesters’ safety, Yang rode his bicycle to the square to warn the university students who were there demanding openness, anti-corruption measures, press freedom, and, ultimately, democracy.

When troops deployed under martial law opened fire on the crowd gathered on Chang’an Avenue (to the north of the square), a bullet struck Yang. It shattered his bladder and caused a severe pelvic fracture. Although he was taken to the hospital, his injuries proved irreparable. He died two days later of an abdominal infection and heart failure, leaving You alone to raise their five-year-old son.

― Do you think that over time the families of the victims are being silenced even more?

“It’s never been easy,” the widow replies.

At that moment, there’s a knock at the door. “The police have arrived. We can’t do this now,” You whispers. “I’m so sorry, there’s no way... I already told you,” she says regretfully. Before opening the door, however, she shares her message to the world: “I would like the government to accept responsibility for what happened in the June 4 tragedy and to give the people answers.”

From the entrance, a uniformed police officer asks the journalists to leave the premises and accompany him. You reiterates her apologies, and her eyes reflect her helplessness. The police station is in the lobby of the building where You lives. The officer takes down the reporter’s identity and warns: “You must ask for permission to conduct interviews.” He doesn’t say from whom. Nor does it seem likely that it would be granted.

The Tiananmen Mothers have been demanding justice and the truth for 36 years. Their members, mostly women, are now well into their seventies. Many of those who were part of this association have passed away, as they recall in the statement they issued on this year’s anniversary. “For each of the victims’ families, those scenes are seared into their memories and can never be forgotten. This tragedy, one of the most atrocious to have ever occurred in the world, entirely caused by the government and leaders at the time, continues to fill their hearts with pain and has become a nightmare from which they cannot wake up,” they write.

“This is a wound that the Chinese people cannot heal, and it is a pain that will remain forever in the hearts of the families. History will never forget those innocent lives that were taken,” continues the statement, signed by 108 people; Mrs. You heads the list of signatories.

For Gao Yu, a veteran journalist imprisoned several times (including during the 1989 protests), repression in China has increased in recent years through technology. “Both of what people say and what they think,” she asserts in a message. Gao has also been forced by the authorities to leave Beijing recently. This is the second time this year, and she believes there will be two more. In her opinion, the generations born in the decades after 1990 “have no political demands” and “know almost nothing about the truth of June 4.” She warns that, “as the Tiananmen Mothers group ages, reporting on the massacre will be limited to outsiders.” Hong Kong, which for three decades served as a safe place to peacefully commemorate the anniversary, has banned holding its traditional vigil in memory of the victims since 2020.

Still, Zhou Fengsuo, one of the student leaders of the 1989 protests, remains optimistic. This human rights activist, who was imprisoned after the protests and sent to Hebei for “re-education,” has lived in exile in the United States since 1995. He is currently the executive director of the NGO Human Rights in China. “More and more young people are joining us. They want to know what happened. More and more capitals outside of China are organizing vigils, and on [Western] social media, our posts have millions of views,” Zhou says in a phone call. “Even if it seems like the Communist Party has successfully erased the memory, outside of China, it remains the most important issue,” he believes.

“During the white paper protests [which precipitated the country’s opening up in late 2022 after the pandemic], many people used the words ‘my duty,’ which are a legacy of 1989,” Zhou recalls. “It’s my duty,” was the response a student gave in 1989 when a journalist asked him why he went to Tiananmen Square. “It’s still an inspiring movement because it was peaceful. And the solidarity, love, and hope that emerged there are part of human history. And that will be respected and remembered forever, because dignity and freedom against tyranny transcend time and space,” Zhou adds.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.