When the criminal legend of ‘El Mayo’ Zambada becomes a ballad: ‘The big M has fallen, over there in El Paso, Texas’

The arrest of the Sinaloa Cartel kingpin in July sparked songs recounting the event, although the figure of the drug trafficker was already a recurring inspiration for (often controversial) corrido artists

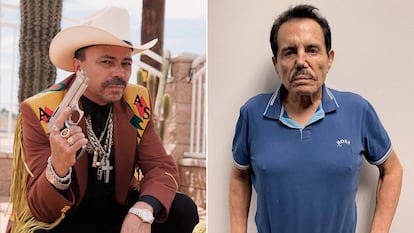

Ismael ‘Mayo’ Zambada, the great Mexican drug lord and founder of the Sinaloa Cartel who never set foot in prison, arrested in Texas. That was the headline with which this newspaper opened its front page on July 25. Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada was arrested at a private airport in El Paso, Texas, where authorities also took Joaquín Guzmán López, one of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s sons, into custody. Before 48 hours had passed since news of the detention of the Sinaloa Cartel kingpins, the machinery of the corrida was already at work. José Heredia, known artistically as El As de la Sierra, released Pacífico triste, a corrido in which he recounted in detail the historic arrest, using controversial lyrics: The big M has fallen [referring to the drug trafficker] / over there in El Paso, Texas / the titan of the business falls / right now he’s behind bars. El Mayo has been a recurring theme of inspiration for artists of the controversial genre, where stories about the capo are recounted as exploits. That way of narrating, added to the idiosyncrasy of corridos, has for decades led to a debate about the limit between telling a story and glorifying crime.

The arrest of the co-founder of the Sinaloa Cartel gave rise to a raft of conspiracy theories: whether he had fallen into a trap, or turned himself in, or it was an agreement between Los Chapitos, the faction of the cartel led by El Chapo’s sons, and the United States. Shortly after his arrest, Zambada’s lawyer told the Los Angeles Times that his client was “violently kidnapped” by Guzmán López. In a letter released on August 10, Zambada claimed that on July 25 he was going to meet with the governor of Sinaloa, Rubén Rocha. The politician denied this and said he had no links with organized crime: “If they said I was going to be there, they lied, and if he believed them, he fell into the trap,” he said at an event in which Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador displayed his support for the governor. In his letter, El Mayo said that the alleged meeting would also be attended by Hector Melesio Cuén, the ex-mayor of Culiacán, who was shot to death at a gas station on July 25, the same day as the drug lords were captured. Last Wednesday, Mexican authorities gave credibility to Zambada’s version of events and issued an arrest warrant for Guzmán López.

El As de la Sierra, a popular musician in the late 1990s and early 2000s, also spoke about the speculation that arose immediately after the arrests, before El Mayo’s lawyer spoke and before the letter was made public: The news speculates / that he gave himself up / New Mexico, Las Cruces / he landed on a jet / being such a big shark / the government captured him. He also refers to the presence of Guzmán López on the scene: With him came a chaparrito / he was also most wanted / today Sinaloa is in pieces / because of the news they have given. El Mayo had a reward on his head of $15 million; Guzmán López, $5 million.

El As’ style carried on the legacy of musicians like Chalino Sánchez. Pacífico triste is a song adorned by the brass of Mexican regional music, a very common sound among artists attached to the essence of the subgenre. References to the famous drug trafficker have featured in dozens of songs, sometimes obscured by covert mentions (“El M,” “El MZ,” “The man in the hat”...) and on other occasions with no attempt to hide the subject: El Mayo.

A low profile

Corrido artists often feed their stories with the reality in which they live, with their context. In the 2000s, amid the war on drugs promoted during the six-year term of Felipe Calderón (2006-2012), the lyrics of the corridos were impregnated with it, addressing the issue of violence from a cruder perspective. It was the era of the altered corridos. In an interview with this newspaper, Eulogio Sánchez, the singer of Los Buitres de Culiacán Sinaloa ― one of the most famous bands of the genre ― explained the reason behind those lyrics: “Why did they sing [about violence]? Because it was the theme of the country at that time [...] Besides, the region where we are from [Sinaloa] is a strategic point for drug trafficking. We live with them every day. I think it would be disrespectful of us not to tell those stories; it is inevitable.”

El Mayo tried to keep a low, almost ghostly, profile during his career as a drug trafficker. He has been spoken of as an austere man, who spent his days in the mountains, in hiding to avoid justice. “The mountains are my home, my family, my protection,” he told Mexican journalist Julio Scherer in a 2010 interview. That theme was used in early August by Los Farmerz and El Fantasma in their song Don Mayo: If they didn’t catch him before / it’s obvious they couldn’t.

A cell, paper and pen

Corridos, like chanson de geste poems, capture reality from an epic perspective, treating the actions of their characters as heroic deeds. The musical subgenre was especially relevant during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917), when the songs recounted what was happening in the conflict. It is this epic nature that has heightened the controversy over the lyrics, where in the case of narcocorridos, or drug ballads, it is often the criminals who carry out these feats. Added to this factor is the tradition of commissioned corridos: songs created at someone’s request for musicians to deal with certain topics or narrate certain events. Sometimes, it is the cartels themselves who request such songs.

UNAM philosophy professor Ainhoa Vásquez warned in an interview that it was important to distinguish between two concepts in which glorification is separated by a thin line: narcoculture and narcofiction. “Narcoculture is what drug traffickers produce for drug traffickers; narcofictions are produced by people who have nothing to do with drug trafficking and for people who have nothing to do with drug trafficking,” she explained.

In the case of the corridos about El Mayo, this narcoculture comes to play a leading role. Jesús “El Rey” Reynaldo Zambada, El Mayo’s brother, was arrested in 2008 as one of the four fundamental pillars of the Sinaloa Cartel and extradited to the United States in 2012. During his stay in prison, he took up paper and pen to exploit a previously unknown facet, that of corrido composer. For his brother he wrote El más conocí, a song that would be embellished by the group Los Intocables del Norte in 2015: With his hat on the side / his gaze and his smile / he has become very well-known / and in his land he is admired / they know that he is a good friend / and also in love.

El Mayo’s presence has crossed the border of drug trafficking culture, to the point of impregnating the discographies of artists such as Los Tucanes de Tijuana ― in 2017 they released El MZ ― or young and controversial current stars, such as Peso Pluma, who alluded to his figure in Zapata (2023): Turn on another green one to de-stress / the MZ is still at work. A playlist created by a Spotify user evidences the drug lord’s roots in the music industry. With 52 songs (almost three hours of music), nearly 20,000 listeners have saved the list in their libraries.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.