Mass arrests and forced transfers: How migrants are exiled in North Africa with European money

An investigation by EL PAÍS with Lighthouse Reports reveals how Morocco, Mauritania and Tunisia use European financing to detain and forcibly displace migrants and refugees. The victims are primarily Black people. The objective: prevent them from reaching Europe

It’s been more than four years, but Timothy Hucks’ blood boils every time he remembers it. In another country, what happened to this New Yorker in Morocco could be considered a kidnapping. In March of 2019, Hucks, who was then working as an English teacher in Rabat, had broken up with his girlfriend. Devastated, all he wanted to do was drink an entire bottle of wine. So, he left a quiche in the oven and his mobile phone on the table and headed out to a liquor store, which was just four minutes from his house. But he didn’t make it back: he ended up being arrested and exiled to a city more than 200 miles from the Moroccan capital. Next to him, there were dozens of young guys. And they all had something in common: they were Black.

Further south, in Mauritania, Idiatou and Bella begged their captors — members of the security forces — not to leave them in no-man’s land, without phones or money, because they wouldn’t know how to return or how to ask for help. But they ended up abandoned and barefoot at a border post between Mauritania and Mali, in an area where jihadist groups operate.

Meanwhile, François, a Cameroonian musician with a six-year-old child in his care, ended up suffering from hallucinations in the middle of a desert area in Tunisia. It took him nine days to get away. This was the first time that the local security forces had left him stranded in the middle of nowhere… but it wouldn’t be the last.

Every year, tens of thousands of people like Timothy, Idiatou, Bella or François (the last three have not given their last names for their safety) end up banished to desert areas or remote cities in North Africa. This is the punishment that migrants and refugees are subjected to when they attempt to reach Europe by boat or by jumping a fence. Thrown in some corner of the Sahara, the largest hot desert in the world, without phones, money, water, or even shoes, those who survive recount kidnappings, extortion, torture, sexual violence, or dog attacks incited by the security forces. This practice, which is systematically applied almost exclusively against Black people, has a silent accomplice: the European Union.

An investigation by EL PAÍS, in collaboration with the non-profit Lighthouse Reports organization and other foreign media outlets, has exhaustively documented how EU funds finance these operations in Morocco, Mauritania, and Tunisia.

Verified sites where migrants were abandoned

Rabat

Beni Mellal

MOROCCO

Tiznit

200 km

MAURITANIA

Nouadhibou

Nouakchott

Rosso

Gogui

200 km

Tunis

TUNISIA

Sfax

200 km

Verified sites where migrants were abandoned

Rabat

Beni Mellal

MOROCCO

Tiznit

200 km

MAURITANIA

Nouadhibou

Nouakchott

Rosso

Gogui

200 km

Tunis

TUNISIA

Sfax

200 km

Verified sites where migrants were abandoned

Tunis

Rabat

Beni Mellal

MAURITANIA

Sfax

TUNISIA

Nouadhibou

MOROCCO

Tiznit

Nouakchott

Rosso

Gogui

200 km

200 km

200 km

Verified sites where migrants were abandoned

Tunis

Rabat

Beni Mellal

TUNISIA

Sfax

MAURITANIA

Nuadibú

MOROCCO

Tiznit

Nuakchot

Rosso

Gogui

200 km

200 km

200 km

“When the European Union gives you money to block borders, you have to get rid of irregular migrants within your territory. Or, at least, [you need to] complicate their lives,” says a European source, who has worked on African programs financed by the EU. “If an immigrant from Guinea is in Morocco and you take him to the Sahara twice, the third time he will ask for voluntary return [to his country],” maintains this interlocutor, who requests anonymity for fear that the Moroccan authorities will make his work difficult.

Early evidence of these operations dates back to 2003, in Morocco. But over the years, such procedures have been systematized. Last summer, they could even be seen on TV: Black men, women and children appeared in front of cameras in no-man’s land between Tunisia and Libya. One photo of a woman and her daughter dying of dehydration in the sand circulated around the world.

Faced with such images, EU Home Affairs Commissioner Ylva Johansson expressed her concern. She also stressed that “European money isn’t financing the deportation of immigrants. That’s totally false.”

However, for more than a year, this investigation has gathered evidence that shows not only that these operations have been well known in Brussels for years, but that they’re carried out thanks to the money, vehicles, equipment and intelligence provided by the EU.

Interviews with more than 50 survivors — as well as a dozen police officers and community sources — emphasize the routine violation of international conventions and treaties on human rights, discrimination and torture. The European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) are also aware of these practices, according to confidential documents that EL PAÍS has had access to. Since 2015, the EU has signed agreements with Turkey, Libya, Tunisia, Morocco and, recently, with Mauritania and Egypt. All of the governments of these countries have been questioned for their deficiencies in respect for fundamental human rights.

In the case of Tunisia, Morocco and Mauritania, the EU has provided them with more than $400 million between 2015 and 2021 under the EU’s Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF), intended exclusively to address the causes of irregular migration. Additionally, the 27 member states pay for dozens of other projects, but the lack of transparency in the financing system makes it impossible to verify how much money is spent and where. The three North African states are among those that receive the most economic support and are key in the European policy of border externalization.

The anti-irregular immigration practices of these countries are “public domain” in the EU, according to a source who worked on the design of the EUTF program in Morocco. In theory, local economies are bolstered, in order to discourage emigration. “These [detentions and forced transfers] have always been done,” says Gil Arias, who served as the deputy executive director of Frontex between 2006 and 2016.

The EU is obliged to ensure that the use of its funds doesn’t violate human rights. However, the European Commission has admitted in writing that it doesn’t monitor this requirement. In response to questions raised by this investigation, a spokesperson states that “all EU contracts have human rights clauses that allow implementation to be adjusted as necessary.” However, two senior European officials privately acknowledge that it’s “impossible” to control the uses of financing and equipment.

This strategy doesn’t seem to work. Irregular immigration continues to increase and has reached peaks not seen since the 2015 refugee crisis: more than 380,000 people irregularly entered the EU in 2023. That’s 17% more than the previous year, according to Frontex. At the same time, xenophobic sentiment in Europe has skyrocketed and immigration is key in the public debate ahead of the European elections in June. The extreme-right stands to win millions of votes at the cost of stoking fear against foreigners.

The persecution of Black people

The modus operandi is similar in all countries involved. The security forces in Tunisia, Morocco and Mauritania arrest sub-Saharan immigrants in raids on the streets, in their homes, or on the boats with which they try to reach Europe. These individuals are subsequently piled onto buses and driven hundreds of miles away to remote areas.

In Morocco, it’s usually the Auxiliary Forces — the paramilitary wing of the state security forces — that patrol in search of people who fit a common profile: those who are Black.

When they see them, they’re forced into a van, often with violence. Other times, the Auxiliary Forces go door-to-door and abduct women and their children. Forced transfers are also very common with immigrants, who try to jump the fences of Ceuta and Melilla (autonomous Spanish cities on the North African coast), as was done en masse by the survivors of the Melilla massacre in June of 2022. The vast majority of the victims were Sudanese refugees. “These are isolated cities, outside the large population centers… sub-Saharan Black people are the perfect target,” explains a Spanish police source, who has experience working in Africa. This agent admits that he prefers to close his eyes to the abuse. “I can’t get involved in the atrocities they do in Morocco. I can’t fix the world by myself.”

Rabat: Play-by-play of an arrest and exile

October 18, 2023

The most serious cases of violence by the Moroccan authorities collected by this investigation occurred near the border with Mauritania. Four Guinean survivors — one of them visibly and badly injured — explain how, upon entering Western Sahara (a territory occupied by Morocco) they were cornered by two groups of uniformed police officers. Some were on ATVs and others were accompanied by dogs. The young people claim that the agents took everything from them and that they were beaten and attacked by the dogs. After two hours of being held in a kind of field barracks alongside several dozen other prisoners, they were abandoned in the sand. Their hands and feet were tied up and they had no water, nor food. After managing to break their zip ties, they were able to get away from the deserted area.

“Some ran away after being released, without helping others. Others couldn’t even walk. Others were seriously injured by beatings and dog bites,” one of them says.

After such a traumatic experience, these Guineans want to return to their country. “No one can move on after the torture we experienced,” they tell EL PAÍS.

The government in Rabat says it thwarted 75,184 irregular immigration attempts last year, although only about 18,000 people were intercepted at sea or at the border, in a clear attempt to emigrate. These numbers don’t specify how many people were transferred to remote areas against their will. In Madrid, none of the agents interviewed believe these figures, which have been released by Moroccan government officials to demonstrate their supposed efficiency. However, these are the only official figures that are made public. In any case, it doesn’t seem to matter to the Spanish authorities, so long as Rabat contributes to reducing the number of irregular entries.

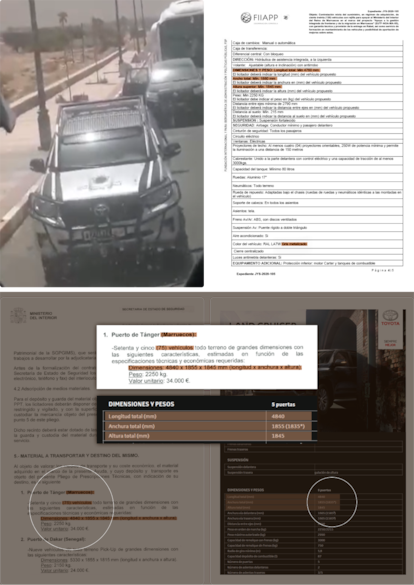

To this end, the EU finances part of the Moroccan operations against irregular immigration, on land and at sea. Spain, meanwhile, individually injects over $30 million annually into Morocco for police cooperation. The Auxiliary Forces and the Moroccan Gendarmerie — two of the security forces involved in the arrests and forced transfers — have received tens of millions of euros from Brussels. And some of the vehicles that Morocco uses for its migrant dispersal strategy are donated by the EU.

Brussels is well aware of the Moroccan government’s practices. In 2019, the European Commission warned of a “campaign” against “sub-Saharan refugees and asylum seekers” in the same report in which it justified the funds being given to Morocco. The authors wrote that several thousand people including women and children “have been illegally arrested and taken to isolated areas in the south of the country or near the border with Algeria.” In another document from Frontex, drafted in February of 2024, it’s noted that “racial discrimination and excessive use of force by police” are employed.

The Moroccan Ministry of the Interior denies human rights violations, although it doesn’t deny forced displacements. It maintains that national legislation provides for the “relocation of migrants to other cities” because it “takes them away from trafficking networks” and “dangerous areas, such as forests and deserts.” Exiles are, according to the Moroccan government, a way to give migrants “greater protection and respect for their dignity.” When asked if there are European or Spanish funds allocated to vehicles and personnel with which the expulsions are carried out, the Moroccan spokesperson issues no denial: “The technical support from Spain and the EU represents a minimal part of the costs assumed by our country.”

Locked up like animals

One day this past January, police officers — with their faces covered and Kalashnikovs in their hands — were guarding the Ksar Detention Center in Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania. It was just over 100 degrees. Behind those walls, Idiatou and Bella — two Guinean women aged 23 and 27 respectively, who were rescued from a drifting canoe with which they intended to reach the Canary Islands — desperately awaited their fate. The images and videos obtained by this investigation show the conditions of the detention center: dark rooms without furniture, except for metal beds or bunk beds that sometimes don’t even have mattresses. The inmates urinate in bottles. There, they are deprived of food, water, medical assistance and, of course, lawyers, according to testimonies from a dozen detainees and reports from several NGOs. Some even report attacks. Children are also imprisoned in this facility, as can be seen in dozens of images of the interior that EL PAÍS has had access to.

A day on guard in front of the Ksar Detention Center in Nouakchott

January 2024

At least 45 people are locked up in the detention center awaiting deportation. Inside, the list of people to be sent to Gogui, Mauritania is being finalized.

Detainees in the center await transfer. Like another group that left the night before, they will also be transferred to Gogui, on the border with Mali.

A white bus leaves the detention center. It heads to a repair shop, about 650 feet away, to prepare for the long trip to Gogui. The driver pays for the tank to be filled and for the tires to be inspected.

The police call the detainees, they believe that they will get back their cell phones, but this does not happen; they are only given their backpacks with the clothes they were wearing.

The bus appears ready to leave the detention center. There are at least 13 women and two of them, Bella and Idiatou, will be sent to Gogui on the next trip.

The white bus is ready and returns from the repair shop to the detention center.

A blue van full of migrants – who have been rescued after two weeks lost at sea – enters the detention center. The bus that was in the repair shop follows.

A blue truck full of migrants enters the Ksar Detention Center. These detained individuals are also part of the group rescued at sea.

The same blue truck – now empty – leaves the location.

The white bus leaves in the direction of Gogui. At the same moment, a second truck full of migrants enters the detention center.

EL PAÍS follows the bus for 10 miles along National Highway 3 towards Gogui. Inside are Bella and Idiatou. Meanwhile, two other minibuses leave the center with the migrants rescued at sea, who arrived just an hour earlier. They are of Senegalese, Malian, Guinean and Ivorian nationality.

Another blue minibus full of people enters the site.

The minibus – now empty – leaves the site.

What happens in these prisons for migrants and refugees isn’t unusual for the European authorities. For instance, journalists on the ground have identified Spanish agents visiting these facilities in Nouakchott and Nouadhibou. In these centers, the authorities prepare lists of detainees who will later be deported. They share these names with the police, according to a source with access to these buildings.

Bella comes from Koubia, a town in the northwest of Guinea-Conakry. At 16, she was married to a man much older than her, who beat her day and night. When her husband died, she left her three children with her brother and decided to emigrate to Mauritania, to make a living for herself. She met Idiatou selling coconuts in Nouakchott and, together, they decided to undertake the journey to the Canary Islands, one of the most dangerous migratory routes in the world, to start a new life in Europe.

After their rescue from the sea, the two women — who say they had Mauritanian residence permits — spent four days locked up in two different detention centers. “The police behaved very badly with us. They had no mercy,” Idiatou recalls. They were eventually put on a bus with 20 other people against their will. The journey, which was nearly 600 miles, concluded 12 hours later at the Gogui Zemmal border post. This is on the border with war-torn Mali, a country that’s foreign to them. Since 2019, the UNHCR has asked that nobody be returned to Mali. The other place where migrants are sent is Rosso, on the border with Senegal, about 120 miles from Nouakchott.

Mauritanian authorities have been arresting migrants since 2006 and then abandoning them on the border with Mali, according to a report by Amnesty International. And they don’t do it alone. The Spanish security forces have been collaborating with them in immigration control for a decade. Part of the activities against irregular immigration in Mauritania are paid for with Spanish funds.

The Ministry of the Interior provides $10 million annually in subsidies for police cooperation, while the Spanish Civil Guard and the National Police work side by side with their Mauritanian colleagues. Spanish agents provide information that allows local security forces to board boats in their attempt to reach the Canary Islands or arrest people on the streets, on the beach, or in shelters where they await boarding.

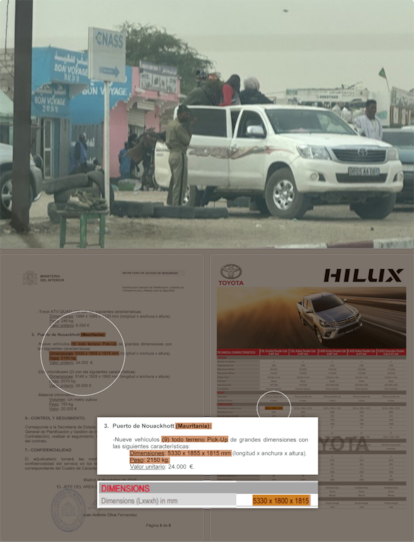

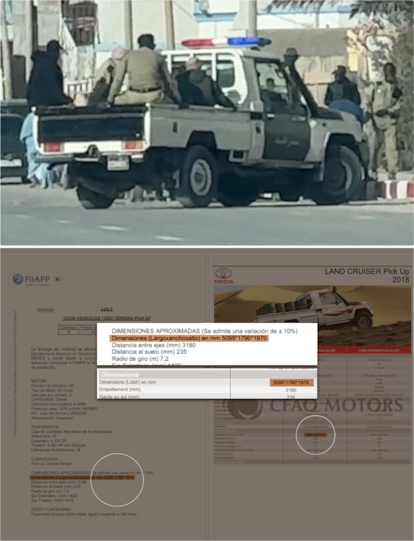

The money also comes from EU funds. European authorities finance, train and equip the Mauritanian police, mainly through FIIAPP. This Spanish agency has also financed two detention centers, one in Nouadhibou and another in Nouakchott. In addition, the Mauritanian police have several types of vehicles with which they detain and transport migrants to the centers, or to the border. Some coincide with those provided by Spain and the EU through the FIIAPP, as can be seen from the purchase contracts that this investigation has had access to.

When asked about this by EL PAÍS, the Spanish Ministry of the Interior neither confirms nor denies that it has knowledge of the expulsions to the desert, nor of the use of vehicles acquired with Spanish funds in these operations. Nor does it respond to the role of Spanish agents in detention centers. The ministry states that there are 50 Spanish police officers and civil guards stationed in Mauritania to fight against human trafficking, “with full respect for the protection of the rights and freedoms of migrants.” The FIIAPP, meanwhile, assures EL PAÍS that the detention centers it’s renovating will improve care for detainees and that the Mauritanian authorities are ultimately responsible for how they use the donated materials. The institution maintains that its managers and the police officers who work on its programs “have never witnessed any actions by the Mauritanian police that have violated human rights.” The Mauritanian government acknowledges the expulsions “to the migrants’ countries of origin,” but maintains that this is a legal mechanism and that the entire process “strictly” respects international laws and conventions.

In November of 2023, a report from the European Parliament warned of “systematic and serious violations of human rights and ill-treatment,” as well as of “abusive expulsions” to Mali and Senegal. Despite this, aid to Mauritania is increasing. Last February, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez and the head of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen traveled together to Nouakchott to announce more than $500 million to develop the country’s economy and stop rafts from reaching the Canary Islands. It’s unclear how this money will be spent by the local authorities.

The irregular journeys to the Spanish islands, in any case, haven’t stopped. Between January 1 and May 15, 16,586 people arrived irregularly at the archipelago… 375% more than in the same period the previous year. The majority came from the coast of Mauritania.

When Idiatou and Bella got off the bus that took them to the Malian border, the agents forced them to cross. “They goaded us like animals,” Idiatou laments. They walked barefoot for four days, until they reached a town whose name they don’t remember. From there, a taxi driver took them to Kaolack, the Senegalese city where some of Idiatou’s relatives live. Exhausted, dirty and with a swollen body, her sister took awhile to recognize her.

The desert as a weapon

François, a 38-year-old Cameroonian with a passion for music, is one of those exiled by Tunisia. The Coast Guard intercepted his barge last September when he was trying to reach the Italian island of Lampedusa, along with his wife and their six-year-old son. The patrol boat came too close and almost flipped them over. “They began to circle around us, with the engines going at maximum speed. I thought it was the end,” he recalls.

The Tunisian government continues to deny these forcible transfers, despite the fact that they’ve even been broadcast on television. “Tunisia refuses to endanger human lives or exploit the vulnerability of people fleeing political, climatic and economic risks caused in part by Western countries,” a government spokesperson maintains. The only returns, he assures the media, are voluntary. However, between July of 2023 and May of this year, EL PAÍS has verified 13 other operations to drop off dozens of migrants in desert areas that border Libya and Algeria.

The violent campaign against sub-Saharan African immigrants was unleashed in Tunisia last year, after President Kais Saied claimed, in February of 2023, that the increase in migrants was part of a “criminal plan” designed to “change the demographic composition” of the country. His statements triggered a wave of racist attacks against Black Africans, including those with residence permits. Since last summer — and coinciding with the commitment by the EU to deliver almost $1 billion in cooperation funds, of which $105 million are earmarked to stop irregular immigration — street arrests and maritime interceptions have intensified.

Von der Leyen has referred to the pact with Tunisia as a “model for the future.” But since last June, at least 29 people, including women and children, have died in the desert after being abandoned on the border with Libya, according to a tally by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya.

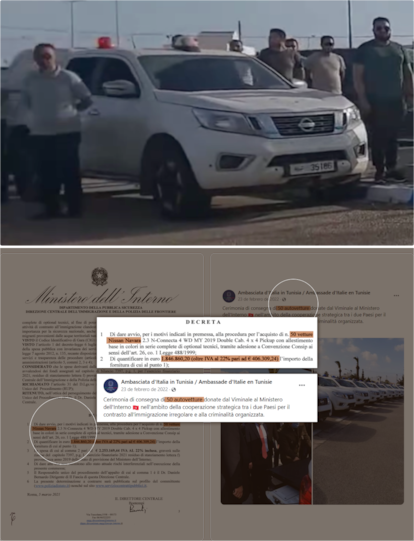

The vice president of the European Commission, Margaritis Schinas, is one of the architects of the current European migration policy. In September of 2023, he gave assurances that the EU “doesn’t finance these practices in any way,” in reference to violent operations against migrants in Tunisia. However, links to donations from EU member states are recurrent. The Nissan Navara pickup trucks that the Tunisian police use for raids against migrants match the make and model of those donated by Italy and Germany. Additionally, Berlin spent more than $1 million between 2015 and 2023 to train more than 3,000 agents from the Tunisian National Guard and the General Directorate of Borders, protagonists in the execution of these operations. Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands, meanwhile, have funded a training center for Tunisian border agents. The EU itself has recently provided the Tunisian Coast Guard — whose members intercept migrants before expelling them into the desert — with equipment such as mobile radar systems and thermal cameras to help them detect ships bound for Europe.

The German Ministry of the Interior confirms that the government is well aware of the practices of the Saied administration. “The German government has harshly and repeatedly criticized the transfer of refugees and migrants to the border area between Tunisia and Algeria in the summer of 2023,” a spokesperson tells this newspaper. Furthermore, they continue, the German government “has repeatedly made it clear to its Tunisian partners that cooperation in the field of migration and human rights must be respected.” The Italian government was briefer upon being queried by EL PAÍS: “No comment.”

The efforts of the EU and its African partners to discourage irregular immigration have led many of those interviewed for this report to abandon their objective. However, many others, such as François, maintain their goal in spite of everything: “I want to reach Europe, the United States, or Canada.” Still, he questions the situation. “Europe itself doesn’t want to do the dirty work alone. Why do they see sub-Saharans as trash? In 1,000 years, in 10,000 years, there will still be someone like me. Someone chasing their dreams, someone far from home, going somewhere.”

Credits:

This investigation has been conducted by Lighthouse Reports in collaboration with EL PAÍS, Der Spiegel, The Washington Post, Le Monde, IrpiMedia, the German television channel ARD, the Moroccan newspaper Enass and the Tunisian online publication Inkyfada. The porCausa Foundation contributed by accessing the FIIAPP databases and contracts.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition