Reconstruction of a shipwreck: How Italy and Frontex could have prevented over 90 deaths in Cutro

On February 26, a boat carrying around 200 migrants capsized 40 meters off the Italian coast. Various agencies failed to detect the risk and did not activate a rescue operation on time. An investigation by EL PAÍS with ‘Lighthouse Reports’ and other media outlets exposes the fatal chain of errors

In the early hours of February 26, at around 5 a.m. and after almost four days and four nights of sea crossing from Turkey, a wooden boat sank off the coast of Cutro, in southeastern Italy. Almost 200 people were crowded aboard the old vessel, mostly refugees from Afghanistan who had paid up to €9,000 to try to reach Europe. About 40 meters from the beach, strong waves rocked the boat; its hull ran into shoals and broke apart. At least 94 people died, including 35 minors. On Thursday of this week, the prosecutor’s office of Crotone (Calabria) ordered a search of the headquarters of the two agencies involved in the operation (the Coast Guard and Guarda di Finanza) and made the first charges for negligence in the rescue tasks.

The Summer Love — that was the name of the old recreational boat — did not arrive near the Italian shores by surprise. The ship had been on the radars of the Italian and European authorities hours before the shipwreck. The overcrowded boat, which got caught in a storm as it neared Italy, had been detected by Eagle 1, an aircraft operated by the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), almost six hours before a shipwreck that was the worst since the tragedy in Lampedusa in 2013, where 368 people died. But in the most decisive hours, Italian authorities looked the other way and the various agencies involved began to blame each other, or else to pass the buck to Frontex. Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni only traveled to the scene of the tragedy 11 days later.

The key to this case, in addition to a chain of errors and the origin of the short circuit that prevented the tragedy from being avoided, is the reluctance of the Italian authorities to activate a search and rescue operation despite the fact that there were multiple indications that one should been ordered. The Italian Coast Guard did not act until the ship had already broken up and dozens of people were drowning a few yards from the Calabrian beach. On March 4, six days after the shipwreck, Prime Minister Meloni spoke from Abu Dhabi and laid the blame at Frontex’s doorstep. “Frontex did not issue any emergency statement,” she said. “Do any of you think that the Italian government could have saved the lives of 60 people and didn’t?”

Three months after the event, a joint investigation by EL PAÍS with Lighthouse Reports, Le Monde, Sky News, Domani and Süddeutsche Zeitung, reveals new data that contradicts the Italian government. Access to confidential documents, a review of about 20 testimonies from survivors and their families, and the analysis of exclusive video footage show that there were enough elements at play — that the Summer Love was overcrowded, that it lacked life jackets and was caught in the middle of a storm — to warrant triggering a rescue operation. But Italian and European agencies did not do enough to prevent the deaths of almost 100 people.

A confidential Frontex document, which had not emerged until now, shows that the ship had “irregularities” that would have required more attention from all parties involved. The document is a 30-page report of the aerial mission of an agency plane that was out on patrol the day before the shipwreck. The Eagle 1 took off just after 5 p.m. on February 25 for a surveillance mission. Since its creation in 2004, the European agency has supported coast guards and national security forces to monitor their borders. The deployment of satellites, drones and planes in the Mediterranean makes it difficult for any ship to escape their control. That was the case with the Summer Love. The plane’s satellite phone detection system did pick up several signals coming from the boat. Apparently, one of the organizers of the trip was trying to contact Turkey. “This irregularity caught our attention,” reports a Frontex spokesperson.

Hiding under the deck

The Summer Love’s voyage began on February 22, 2023, with around 200 people on board. Most were Afghan refugees, but there were also Syrians, Pakistanis, Turks and Tunisians, including dozens of minors. They had left Istanbul two days earlier, hidden in the back of a truck that took seven hours to reach the Turkish city of Çeşme. The group had to walk three hours through a forest to reach a rocky beach, in an isolated spot, where a boat was waiting for them. But it wasn’t the Summer Love.

The first boat they got on was a tourist ship, smaller and with more metallic components than the one that ultimately took them towards Italy. Three hours later, the engine broke down and the boat began to take on water. “Oil was dripping on my head and the boat was too small. We were lucky that the sea was calm,” recalls Nigeena Mamozai, a 22-year-old Afghan woman who lost her husband in the shipwreck four days later.

The occupants had to wait another three hours until they were picked up by a white and blue boat. The Summer Love was the type of classic wooden schooner used by tourists to navigate the Aegean Sea, larger and with a capacity to transport about 20 people. But it was also older, fragile and slower than the first ship, according to the testimonies of the survivors collected by the Italian justice system. Someone had removed both masts. And just like with the previous one, its engine did not work properly and it had to make dozens of stops during the journey, some survivors recounted.

During the four days that the voyage lasted, most of the passengers were forced by the smugglers to remain hidden in the cabins below the deck to avoid being located by the surveillance patrols. Witnesses have described a very tense atmosphere. They speak of days without food and without enough water. Some of them clashed with the organizers because they were prohibited from calling their relatives or smoking on deck. In some videos provided by the survivors, however, some moments of joy can be seen as the ship approached the Italian coast.

An “unusual” number of people

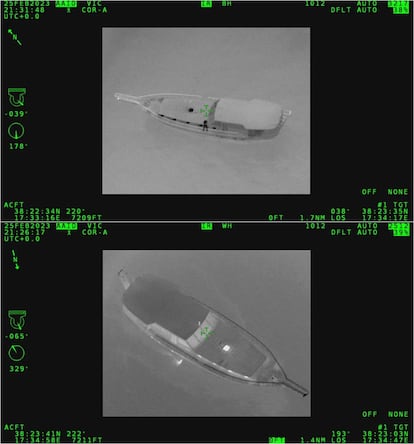

According to the confidential report of the Frontex air surveillance mission, to which this investigation has had access, Eagle 1 located the Summer Love at 10:26 p.m. and classified it as a “suspicious target.” From the air, only one person could be seen on board, but the agency reported from the beginning, contrary to what the Italian government has claimed, that it was a “possible migrant boat.” The aircraft also reported a “significant thermal response,” suggesting the presence of a large number of people on board. The agency itself, in response to questions for this investigation, said that another of the “irregularities” that drew its attention to the ship was “the detection of an unusual number of people below deck.”

The aerial recording could be followed in real time from the agency’s headquarters in Warsaw, where, in addition to Frontex analysts, Italian agents are also stationed.

The agency sent that report to a long email list that included Italy’s maritime coordination centers and their managers. It did so at 11:39 p.m., almost five hours before the shipwreck. In a previous communication, echoed by the Italian media at the time, Frontex recorded in writing that the buoyancy of the boat was good, but that no life jackets could be seen. The document also maintained the possibility that there might be more people under the deck.

Rome was also fully aware of the difficult weather conditions that the ship might face on its approach to shore. At 9:00 p.m., the records of the Guardia di Finanza, Italy’s financial crimes police force that also holds a remit over customs and borders, show how one of their patrol boats on an anti-immigration mission had to change course due to the bad state of the sea. Almost six hours before the shipwreck, the pilot of the Frontex aircraft in charge of monitoring the Summer Love also warned his superiors about the strong winds, according to the transcripts to which this investigation has had access. As required by protocol, these communications were also shared with the Italian authorities. Overcrowding, a lack of life jackets and bad weather are all signs of danger, or “distress” in maritime terminology, according to both Frontex’s and Italy’s own rules.

Matteo Salvini, Italy’s Minister of Infrastructure and Transportation and head of the Coast Guard, assured in an interview with EL PAÍS this Thursday that this danger did not exist. ”Frontex, the Coast Guard and all the authorities confirmed that they did everything possible, and even the impossible. Nobody avoided their duty. And Frontex, evidently, had not indicated any imminent risk. Otherwise, the Coast Guard or the Italian Navy would have intervened,” he said. “I have read the records. [...] I refuse to believe that a sailor would not save someone’s life if he knew the person was in danger. And evidently there was no warning of a life-threatening danger.”

In the port of Crotone, an hour’s sail from the ‘Summer Love,’ there was an Italian Coast Guard launch capable of intervening. In fact, it had gone out on similar missions in more difficult weather. But the Italian authorities remained reluctant to order a search and rescue operation.

It was not just a decision based on the laws of the sea or the interpretation of data collected on a stormy night when waves were higher than two meters. The Cutro case is set in a political context in which immigration has once again become one of Italy’s main electoral and political battlefronts. Tension was high at the time. Meloni and the far-right coalition she leads, in which Salvini serves as deputy prime minister, campaigned on the promise of curbing the arrivals of immigrants by sea. However, so far in 2023 they have quadrupled. On the one hand, the government is trying to prevent these landings. On the other, it has sent a clear message to Brussels that the issue must be addressed by all EU partners.

Italy has had six different governments and five prime ministers over the past 10 years, from the left and the right. But despite political upheaval, the death toll has remained constant and the EU is no closer to an agreement. Since 2013, more than 26,000 migrants have lost their lives in the Mediterranean Sea, according to the International Organization for Migration, the majority trying to reach the coast of Italy. Today, due to the bureaucratic hurdles imposed by Italy on NGOs working to rescue migrants at sea — Meloni’s government now assigns ports for such vessels far from the rescue zone — most NGOs that had boats in the area have decided to withdraw them.

Italian immigration policy is played out on the water. And the resistance of the authorities to prioritize rescues over control has increased in recent years. From 2019 through the first two months of this year, 232,660 migrants arrived in Italy by sea in more than 6,356 landings. Of these, only in 25% of cases was a search and rescue operation activated. The remainder, such as the Cutro shipwreck, were treated as a police operation. That figure contrasts with 2016, which broke all records for arrivals when 181,346 people disembarked on Italy’s shores. That year, rescue operations accounted for 98% of interventions. “In Europe, many countries are not in a hurry when it comes to rescuing migrant boats in distress,” says Professor Maurice Stierl of the University of Osnabrück in Germany. “On the contrary, they take their time, as if to discourage migrants.”

Vice Admiral and former Coast Guard spokesman Vittorio Alessandro confirms this change in approach: “Many manifestly dangerous situations are now recorded as migratory events [in which a police operation is activated], whereas before they were identified as rescue situations.” Alessandro points out that just because a ship’s engines are running does not imply it doesn’t need assistance. “That ship, as photographed and described by the Frontex plane, was heading for ruin because it was overloaded.”

Following Frontex’s tip-off, the Guardia di Finanza informed the Coast Guard that the sighting warranted an investigation, but the Coast Guard decided not to intervene on the grounds that no distress call had been received and that there was no certainty that it was a vessel with migrants on board. However, there were plenty of indications that it was not a regular pleasure boat: multiple calls had been made by satellite phone to Turkey, the thermal response identified by Frontex suggested there were many people on board and the boat’s course made it clear that it was heading for the coasts of Crotone, which are renowned both for being extremely hazardous and as a regular arrival point for boats with asylum seekers on board.

Furthermore, weather conditions continued to deteriorate. Between 3:20 a.m. and 3:33 a.m., almost four hours after Frontex sent its report, two Guardia di Finanza patrol boats, deployed to intercept the vessel, were forced to turn back. “Faced with difficult weather conditions and the impossibility of proceeding in complete safety, the units returned to their mooring base,” reads a report from the corps’ regional command. Despite the patrols turning around, the Rome-based Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Center (IMRCC) did not issue any mayday signals to request an immediate rescue of the vessel. “As soon as you are forced to turn back due to sailing conditions, you must declare a case of distress,” says a senior Italian Coast Guard official who requested anonymity.

Meanwhile, anxiety began to spread on board the Summer Love. Some passengers caught sight of land and called family and friends who were waiting for news of their arrival. Many were already preparing to disembark; they had been promised that they would be able to do so around midnight. At 3:50 a.m., one of the passengers left a voice message on the phone of a relative in Germany: “Luckily, we have arrived on the other side of the world. We will call you as soon as we have internet,” said the man, who was traveling with his wife and four children.

At that moment, the Summer Love appeared for the first time on the radar of the harbor master’s office in Vibo Valentia. Five minutes later, at 3:55 a.m., the harbor master informed the local police and the police forces of Catanzaro and Crotone to be ready to patrol the beaches when the boat reached the coast. But tension was growing on the ship. As the Summer Love approached the beach of Steccato di Cutro in a heavy swell, more and more passengers wanted to issue a call for rescue.

Around 200 meters from shore, the flashing lights of a boat coming from the beach startled one of the ship’s captains. Believing that it was the police, he made a hard turn to steer away, according to the Italian Ministry of the Interior. The high-speed change of course sent the vessel straight into a sandbank. The weight of the boat dragged some of its passengers to the bottom of the sea. Survivors recount how they began to fall on top of each other while water began to flood the cabin. The Summer Love broke into several pieces.

It was not until 4 a.m. on February 26 that a call to the emergency services reported a possible shipwreck just two nautical miles off the coast. The call was received at the Carabinieri headquarters in Crotone. “Help!” was heard in English. The call was cut off and the Coast Guard was unable to recover the communication, according to its official report.

‘I lost him in the waves’

Mamozai remembers how, after that call, her husband put his phone in his pocket, took off his jacket and told her: “Now it’s time to swim.” “With the storm and bad weather, bigger waves started coming in, and we were thrown against the sides of the boat. A huge piece of wood hit Seyar, my husband, in the back of the head. The water separated us. I tried to find him, I shouted his name, but I got no answer. I lost him in the waves,” recalls Mamozai. She was not the only one.

Assad Almoulqi, a 22-year-old Syrian, grabbed his younger brother Sultan, 6, and jumped into the sea with him as the boat began to flood. It was the fourth time Assad had attempted to reach Europe. “My brother died from hypothermia, not from drowning. We were in the freezing water for three hours clinging to pieces of wood and after 40 minutes, my brother died. I had planned out all the scenarios, like swimming with my brother and protecting him. What I didn’t expect was that the water would be so cold,” he recalls at a shelter in Hamburg, Germany. Several survivors have recounted how many of their relatives slipped away when they were holding hands, how they were looking for their babies in the middle of the sea. After a few minutes, silence fell. The Summer Love began to sink, taking dozens of people with it.

The Coast Guard dispatched two speedboats and a helicopter at 4:14 a.m., almost six hours after Frontex located the boat. The patrol departed from Crotone and took one hour and 25 minutes to reach the area of the wreckage, by which time it was too late.

A senior Coast Guard official who asks to remain anonymous believes that the incident was due, in large part, to an error of judgment on the part of his colleagues in the Guardia di Finanza. The officer also points to the “gray areas” that persist between police operations and maritime rescue operations. A 2005 Italian Interior Ministry decree dictates that any suspicious vessel beyond 24 nautical miles (44 km) from the coast must be subject to continuous surveillance, but that a rescue operation will only be launched in the event of “grave and imminent danger” to the vessel’s occupants. In the case of Cutro, says the senior official: “This vagueness allowed the Guardia di Finanza to say: ‘We are taking over because it is a police operation,’ whereas we should have used the precautionary principle. If there is the slightest probability, however minimal, of a shipwreck, the means must be provided to launch a rescue operation.” The officer criticizes the “short circuit” that led to the disaster.

Salvini disagrees on this point as well and goes further, arguing that the rules governing rescues should be revised to restrict them in the case of migrant boats that have paid their passage to reach Europe illegally. “It has been proven that they are organized trips. A SAR implies a rescue for an unforeseen event. In this case, the trips are contracted on the internet: they cost between $5,000 and $10,000, with a starting point and specific duration […] The traffickers are the criminals, not the Coast Guard.”

When news of the shipwreck went around the world, Frontex published some aspects of their internal reports but did not mention in their public statements that, for example, their plane was forced to divert because it was “unable to complete the pattern due to strong winds.” In its statements to the media, the EU agency claimed to have scrupulously respected its mandate: to alert the Italian authorities, who alone are responsible for launching a rescue operation. “The vessel was sailing in an appropriate manner. And the sea was reasonable. It had a constant route, and the wind was behind it,” Frontex director Hans Leijtens told the European Parliament on May 23. “If we know today what we knew then, I think we [would] not do [anything] different.”

The Guardia di Finanza blamed the tragedy on the Coast Guard for not having acted adequately. The latter, for its part, blamed Frontex for not having given them sufficient warning. Neither of the two has been willing to answer questions from this investigation on the grounds that the case is in court. All three agencies had the same access to the same information at the same time. All three failed in the rescue.

Abbas Azimi, Olivier Bonnel, Sara Creta, Bashar Deeb, Youssef Hassan Holgado, Maud Jullien, Lena Kampf, Kristiana Ludwig, Siobhan Robbins, Jack Sapoch, Simon Sales Prado, Tomas Statius, Dorothee Thiesing and Klaas van Dijken contributed to this investigation.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.