The battle for the Mediterranean

The gulf between two very different worlds has turned the Mediterranean into a graveyard. Thousands of people die each year trying to cross it. We traveled to the coast of Libya and the black hole of this humanitarian crisis.

The gulf between two very different worlds has turned the Mediterranean into a graveyard. Thousands of people die each year trying to cross it. Governments and NGOs are involved in their own war over two conflicting visions of the tragedy. In September of last year EL PAÍS traveled to the coast of Libya and the black hole of this humanitarian crisis aboard the Cantabria, a Spanish navy ship manned by the EU naval mission working in the area to disrupt the business model of human smuggling in the Southern Central Mediterranean.

Spanish Navy Rear Admiral Javier Moreno Susanna was leading this EU mission, known as EUNAVFOR Med, whose mandate it is to tackle the human-trafficking networks launching unseaworthy rubber dinghies – known in Spanish as ‘pateras’ – off the Libyan coast with tens of thousands of immigrants bound for Italy. (In mid-December, Spain passed the duty of Force Commander to Italy.)

The admiral sits at the head of the table and asks for a “sit rep.” His cabin is not unlike a movie set. The door opens and in walks Commander Martín Prieto, who tells him that the rest of the boats “are in the thick of it”.

The Italian destroyer Andrea Doria has been called to three SAR – Search And Rescue – events. The Vos Hestia, a Save the Children boat, is onto four more. The SeeFuchs, a boat belonging to a German non-profit, is at the scene of yet another, as is the William B. Yeats, an Irish war patrol ship. And one more patera has been spotted in trouble six miles from the Libyan coast. The Astral, a boat manned by the Spanish NGO Proactiva Open Arms, is close to it and the Zeffiro, an Italian frigate, is on the way. Meanwhile, the Cantabria, a replenishment tanker acting as the EU mission’s headquarters, is following at 18 knots – with us on board.

In short, there are 10 pateras carrying a thousand immigrants and a substantial piece of Europe sailing on international waters a mere stone’s throw from Libya. Aboard these ships are civilians, police officers and military personnel. There is only one element yet to come on board. “Any news of Libyan patrols?” the admiral inquires. The commander frowns and the admiral brings the scene to a close. “Let’s do a good sweep before it gets dark,” he says.

This is Admiral Moreno Susanna’s 15th day leading the mission. The sun beats down and the sea and the sky merge. It is one of those days which, according to an Italian colleague, “last for 26 hours with the situation changing every minute.”

This is September 2017, when Spain responded to a call for help from the Italian government. The hopeless rift between the developing and developed world had already turned the Mediterranean into a battlefield between NGOs, Europe’s military and security apparatus, and Libya – that black hole where human smuggling is one of the few businesses to thrive, with a turnover of around €5 billion a year. Around 600,000 people have reached Italy using this route across the Southern Central Mediterranean since 2014. More than 10,000 have died in the attempt. And gradually, news of this vast migratory graveyard is being brought to our attention.

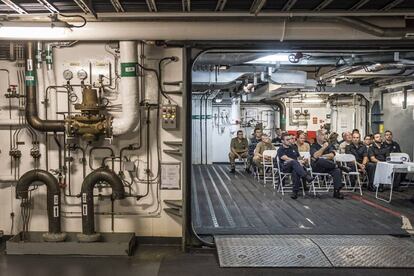

The Cantabria belongs to the Spanish Navy and it is the second-largest ship in its fleet. Measuring 170 meters in length, with a beam of 23 meters, it carries two helicopters and a Spanish naval crew of 150, not to mention 45 officials from 15 different EU countries. To provide accommodation for them all, containers have been spread across the deck. Several of these units act as campaign quarters. Others are used for napping and out of these sails a symphony of snores. Clocks are set one hour ahead and Mass is taken in Latin, allowing everyone an equal chance to follow. In the officials’ quarters, CNN is on TV. While they wash, a Spaniard, an Italian and a Finn chat about the day’s prospects, with one remarking: “I think the next lot will come out of Sabratha,” a Libyan city 60 miles from Tripoli.

When the distress calls sound, volunteers and NGO workers quickly push their boats out to sea. In 2015, non-profits were performing 5% of the rescues. By 2016, this figure had risen to 40% with 12 boats in operation. But a concerted smear campaign has interfered with their response, according to Amnesty International. Non-profits have been accused of creating a pull factor for migrants and of collaborating with the traffickers.

Fabrice Leggeri, director of Frontex, the European border agency, complained in August that the NGOs were picking up migrants ever nearer to the Libyan coast, encouraging the traffickers to load even more people onto their fragile vessels and reduce the amount of fuel on board. The non-profits’ lack of cooperation with authorities, he added, made it “even more complicated to get information about the trafficking networks and to launch investigations.”

What some consider an emergency, others see as a lost opportunity to nail the traffickers. The criticism that NGOs have become a ‘ferry service’ for the migrants was leveled. “They planted the idea that we were the problem, which is an ill-intentioned lie,” says Hernán del Valle, director of Humanitarian Affairs for Doctors Without Borders (MSF). “They want to remove us from the equation because the media exposure of the tragedy is politically uncomfortable.”

That summer, hostilities escalated. The Libyan Coast Guard declared that they would take care of the SARs in international waters. Their patrol boats, four of which have been provided by Italy, began by firing warning shots and telling NGO workers that they would be fired upon if they entered Libyan waters. At the same time, the Italian government demanded that the NGOs sign a code of conduct, endorsed by the EU, in order to operate.

This document forbade them to enter Libyan waters or communicate or send light signals, which facilitates the launching of the pateras –despite the fact the NGOs have always denied doing this. It also obliged them to comply with orders from the Maritime Rescue Coordination Center in Rome and to take police officers on board to gather intelligence and detain traffickers, if need be. Four NGOs refused to sign, among them MSF and the German organization Jugend Retter, whose boat was seized in Italy recently and those on board accused of “fostering clandestine immigration.”

At the end of the summer, we ran into a group of firefighters from Seville working for the NGO Promaid, in Malta. While they got a rickety fishing vessel ready, they discussed whether or not to sign the code of conduct. The problem was the German NGO they had hooked up with to cut costs, whose members described themselves as “left-wing activists”. The same thing happened in the Aegean Sea, says Antonio Reina, the chief of the Spanish contingent. “We were all very different from one another.”

The firemen had been operating out of the Greek island of Lesbos during the refugee exodus across the Aegean until that route was closed off with a €6 billion deal between Turkey and the EU, which involved Turkey sending one Syrian refugee to Europe for permanent resettlement in exchange for the return of a migrant entering Greece through the Aegean.

In Lesbos, three of their colleagues were arrested and accused of human trafficking. Things don’t look much better now. They know the risks of getting close to Libya, and how difficult the Italians can make things if the document is not signed. Accustomed to orders and hierarchies, their take on the code of conduct is: “If you want to play, you have to accept the rules of the game.” The Germans are suspicious of the authorities and less pliable. But they all signed in the end, and are now all subjected to warning shots and to Libyan patrols boarding their boat. But between September and December, they would rescue more than 600 people before going home.

The NGOs share these troubled waters with three European missions and one from NATO. Between them, they have 20 ships and boats, a dozen aircraft and a couple of submarines, which come and go. But there was a period when the sea was almost unmanned, with a consequent cost to human life. In 2013, a wreck with 366 bodies on the shores of the Italian island of Lampedusa sent shock waves across Europe. Italy launched Mare Nostrum, the first military mission of its kind to resolve a civilian crisis. It plucked 150,000 people out of the sea. But it was costing the Italian government €9 million a month and shut down within the year. Frontex took over. In 2014, Operation Triton was launched. In 2017, on a budget of almost €40 million, they arrested around 250 traffickers and rescued approximately 21,000 people. Then an even bigger mission, the EUNAVFOR Med, came into operation following yet another tragedy in April 2015, when 800 people drowned.

The EUNAVFOR Med’s mandate was clear: fight the traffickers. But the mission has also pulled more than 40,000 people from the sea and its name has been softened to Operation Sophia, in honor of a migrant baby born on one of its ships. The entire EU, with the exception of Denmark, is participating in this difficult assignment that has at its disposal four vessels, four aircraft, two helicopters, one submarine and more than a thousand military personnel, and operates on a budget of around €6 million for a year and a half, with expenses on top. Italy and Spain are footing most of this bill – in 2016, Spain contributed €67.2 million.

The situation is analyzed inside the Cantabria’s war room, a sealed windowless space with signs that read EU Secret. One screen shows a map with real-time information about all the ships in operation. Another screen shows a photograph of a boat taken 15 minutes earlier from a Luxembourg aircraft. That makes 11 pateras in one day. And it looks as though the migrant boats are coordinated. According to Admiral Moreno: “They now launch en masse to saturate the area. It makes it more difficult to catch the traffickers.” Abati agrees. “The situation is critical,” he says. One dinghy has already been rescued. Four ships – three military and one manned by an NGO – are dealing with the other 10. And though Admiral Moreno Susanna is quiet, you can feel his concern. When these four finish up, they will head to Sicily to deposit the rescued migrants. And the Cantabria will then be left to face Libya alone. And since he has taken command in September, has he not yet been involved in a rescue.

“They planted the idea that the NGOS were the problem, an ill-intentioned lie,” says the head of MSF

The admiral admits that Operation Sophia has also been accused of being a “ferry service.” Hence, they often repeat the main thrust of their mission: to detain the traffickers and bring them to justice. But their ability to act is limited. Sophia received a mandate consisting of four phases. The first – to gather information, was completed in a question of months. Phase 2A – the capture and destruction of the migrant boats in international waters, has been underway for the past two years. The next two phases involve moving into Libyan waters (Phase 2B) and Libyan land territory (Phase 3), but that requires a resolution from the UN Security Council or a petition from the Libyan authorities in Tripoli.

Currently, Operation Sophia can only act within a margin of two or three miles from Libyan waters. At times, if they’re quick, they can catch the individual towing the pateras or maybe arrest the ‘jackals’ – the people who pick up the motors and pateras that have been left behind. But as a Frontex boss with experience in Med missions said, “Without going into Libya, you can’t do anything. What the devil are we going to do against the traffickers from out at sea?”

We are woken on our second day on the Cantabria by the noise of uniformed men and women making their way to the rallying point. An official announces: “We are close to Libya, and the other units are disembarking. We are practically alone. The aircraft have been making the rounds and will alert us if they find anything. I would like to do a drill so we are prepared.” But it doesn’t seem like a drill. After several minutes, the admiral adds from his cabin: “We have entered a scenario in which we are going to pick up immigrants. Let’s go.”

Inside the war room, more details emerge. The Italian commander, Abati, explains that the aircraft has detected a patera. The images suggest there are no escorts or jackals around. The NGO vessel SeeFuchs has seen a rubber dinghy within the 12-mile limit but has had problems with the Libyan coast guard. The Coordination Center in Rome is trying to declare a SAR event. But first it has to make the situation clear to the Libyans. “We’ll head for the area while they decide,” says the admiral. A barrage of rapid-fire information is exchanged in both English and Spanish. “We’re 50 miles away.” “Maximum speed.” We have another call.” Mike, any point?” “The call has been confirmed by UHF, we have a second.” “The Astral is very close.” “They have a Spanish flag.” “Zoom in on the image.”

The image shows a rubber dingy, dozens of faces and legs slung over the side of the patera, which sags under the weight. The chiefs of staff scrutinize the image to see who is working the engine. “They are the first to be questioned,” they explain.

Meanwhile, Commander José María Fernández de la Puente, a former jet pilot, orders an aerial reconnaissance. It’s 11am and the helicopter disappears into the fog. The pilots take out their binoculars and twist the infrared viewfinder until they see Tripoli. They are flying just 25 miles from the Libyan capital. The search begins. They spot a boat adrift and empty. They take a photo and enlarge it. They can see bicycle tires that are meant to have served as life jackets. And a date – it’s one that was rescued yesterday. But shortly, they locate another boat that is almost obscured by the mist. They approach and confirm. It’s the one they were looking for with 50 people on board. They take photos. Then, on the way back to the Cantabria, they come across another one.

By the time the aircraft lands on the ship, the rescue launches are already in the sea and they move closer to the first patera. The European officials look out from their containers. The crew pull on white jumpsuits and masks in preparation. There is a field hospital ready and an area for photos as well as tables for identification. A voice comes over the radio, saying “Three women and four children”. They throw life jackets into the rescue launches and start one of those 26-hour days, one when their core business appears to get forgotten.

This is the argument the British government used in July when it produced a report on Operation Sophia’s success, or lack of it. “People smuggling begins onshore, so a naval mission is the wrong tool for tackling this dangerous, inhumane and unscrupulous business. Once the boats have set sail, it is too late…”

"Operation Sophia has failed to meet the objective of its mandate — to disrupt the business model of people smuggling. It should not be renewed. However it has been a humanitarian success, and it is critical that the EU’s lifesaving search and rescue work continues, but using more suitable, non-military vessels.”

It went on to argue that, despite the EU’s mission, 180,000 people had entered Europe from Libya in 2016 and 5,000 had died, the highest figures to date. And 2017 appeared to be equally ineffectual. They had destroyed almost 500 dinghies and arrested more than 100 suspects, but most were “low down in the food chain.” Only one of the arrests involved a leader of a smuggling ring – an Eritrean. In Italy, thousands have been arrested and hundreds sentenced, the majority for manning the pateras and compasses, but few of the leaders had been caught in a business that begins in the countries of origin and is often mixed up with corrupt governments.

Luca Raineri, an expert on Libya from the Superior School of Sant’Anna de Pisa and a member of Eunpack involved in the EU’s response to the crisis, attended a closed-door meeting not long ago with Sophia officials. The impression he took away was not good: “They focus on a very small part of the chain and they lack the means to share intelligence adequately in order to get the complete picture,” he observed.

The sun rises on the 410 migrants aboard the Cantabria, silent witnesses to the conflict

Suddenly, however, the figures went into reverse. In 2017, the numbers entering Italy dropped below 130,000 for the first time in four years. The turning point came in the summer, perhaps due to the increased obstacles facing the traffickers. And perhaps this lay behind the British report’s support of one aspect of the mission; the training of the Libyan coast guards. This was carried out on Sophia ships in Malta, Crete, Rome and Tarento. Frontex, ACNUR and OIM have been involved and around 200 coast guards have been trained. The aim is to train 500 and for the Libyans to gradually take control of their own border. The UN, however, has warned of the risks involved in condemning thousands of people to stay in a country that commits “serious human rights violations” and advised international supervision.

For months, EL PAÍS SEMANAL unsuccessfully requested access to these training sessions, although we managed to shake the hands of two students during a November meeting in Rome, where dozens of officials hailing from the front lines of Mediterranean countries had congregated.

The Libyan commodores have time to tell us that their training has been worthwhile before being interrupted by a tall man whose presence prompts them to fall silent. They are, however, the stars of the event and are greeted accordingly. “Buon giorno, good morning, As-salāmu ʿalaykum.”

Enrico Credendino, Operation Sophia’s top overall commander, highlights the drop in numbers. “It shows that the business model of the traffickers can be tackled,” he says. Meanwhile, Federico Bisconti, Admiral of the Italian mission Mare Sicuro, the only one from an EU country with access to Libya, insists that the training means “fresh hope” and goes on to speak about the Italian warships used by the Libyans and a landmark SAR event that was carried out by their coast guards “with total independence.” Vice Admiral Clive Johnston, who heads NATO’s Allied Navy Command and whose Sea Guardian mission has been patrolling the area since 2016, speaks about “our partners in Libya” and congratulates them “for their extraordinary achievements in the last year.”

Only one of the speakers addresses the origin of the problem. Michael Spindelegger, a former vice chancellor of Austria and director of a think tank on migration, poses the question of whether these four years have represented “a passing storm” or rather the harbinger of what is yet to come. “If you study what drives migration – conflicts, demographics, economic development and the gulf between poverty and prosperity,” he says, “we can only conclude that the potential impact will increase over the next few years.”

As the Libyan route has become harder to navigate, arrivals to Spain have risen from 8,000 to 20,000 in the space of a year, suggesting that the migrants have once again changed their route into Europe. According to Colonel Fuente Cobo, an expert at the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies, we find ourselves “very much at the start” of something more serious. “The population in Africa is growing at an explosive rate. Part of that can be absorbed by its own development, but not all. You can understand it better by applying the laws of physics. Europe is on the edge of a demographic catastrophe. If you create an empty space, it is only natural that others should come to fill it. And they’ll do it using the path of least resistance.”

Since the fall of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, this path has been Libya – “a country that is not a country,” according to Bernardino León, a former UN Special Envoy who goes on to explain that until the Arab Spring swept across the north of Africa, this part of the world had acted as a screen, hiding what was happening further down from Europe. But in 2011, “a window of more than 2,000 kilometers” opened up, allowing the problems of the Sahel in.

León warns against short-term solutions, such as EU pacts with Libyan factions to control the migrant flow. According to the UN, as well as to NGOs and journalists on the ground, some of these factions are, in fact, militias involved in trafficking themselves who have switched to the other side in exchange for European payment. “I don’t believe it works,” he says. “Anything that involves potential deals with these networks is a delicate matter, almost as though we are compensating those who are carrying out an illegal activity.”

On the deck of the Cantabria, the fallout from the Sahel’s war and misery is spread out like a map. Once the first two pateras are rescued, the men eat under a mesh while the women and children are ushered inside. The children have been playing soccer with the crew. The onboard doctor gathers the little ones for a group photos and shouts “Say cheese!” And just then, a new patera is spotted. “They have a baby on board,” someone warns the doctor.

This third patera seems to have come straight from hell. The baby, a newborn, is brought aboard and wrapped in blankets. They hurry with it to the infirmary. It is covered in dry scabs and its umbilical cord is still hanging from its belly. “I need people!” shouts the doctor.

The women are helped aboard. One takes a few steps and faints. “Do you know who the mother is?” They keep rescuing people. The stench is overpowering. As soon as they sit down, the migrants pour water over their heads. The baby doesn’t cry. It’s as though it had been struck dumb. They clean him with distilled water and gauze. “They are real survivors,” says the doctor, flexing the newborn’s arms. “Look at his reflexes.”

“Someone is being brought on a stretcher!” shouts one member of the rescue team. It’s a boy with a dislocated pelvis and feet that have been burned raw by the fuel mixed with seawater in the bottom of the boat. He is Nigerian. Most people on this boat are Nigerian. For several years, Nigerians and Eritreans have been the biggest groups entering Italy. Many are young women with beautiful names, such as Joy and Blessing, and a contract already signed for a job in prostitution.

The day does not end there. “The Astral at eight miles,” comes the announcement. It is 8pm and the Spanish NGO boat has rescued around 30 people. The Cantabria approaches it so the Astral can offload the migrants, who will then be shipped to Sicily. Just before sunset, another empty patera appears. The captain recognizes it as the first boat spotted the previous day. A launch is sent out towards it. They cover it with petrol and set it on fire to avoid its reuse. The black smoke rises against a bloodshot sky and Arturo Arcay, the admiral’s assistant, says it was like this or worse until July. “It got to the point that there were 43 boats a day, complete madness,” he says. With his eyes trained on the fire, he talks about the NGOs that have since abandoned the scene, and recalls the tug of war with the Libyans who originally said they would take care of the rescues in international waters and then had a change of heart. And he mentions the EU’s future monitoring of the coast guards, adding that perhaps soon the mission will be able to get to the south shore. The smoke trails off and he shrugs. “It’s an evolving mess,” he concludes.

Shortly afterwards, under a starry sky, the launch comes near the Astral. Tripoli is a glow on the horizon illuminating the sailboat’s bow, which is weighed down with people. There is a Spanish flag and an EU flag and a Libyan flag. The NGO has reported warning shots and collisions and says it has even been dragged to the other side. The volunteers and the Cantabria crew exchange greetings. “Hey man! How’s it going?” they ask each other. There are balloons and banners on the boat. The migrants start to be transferred onto the Cantabria. One member of the Astral blows goodbye kisses to the rescued migrants as they go. And, his job done, the Cantabria’s commander sends the NGO a bottle of wine.

The ship then heads for Sicily, with 410 migrants on board. During the two-day crossing, a member of Frontex and a Finnish border guard try to find out if there are any suspects among them. The officials meet to continue piecing together the bigger picture. “Libya has returned 120 Sudanese and 82 citizens of Burkina Faso,” says one. “The traffickers are under pressure and some have closed down their operation. They are getting ready to hand over those who were about to take the boat to the authorities. We hope to stop 10,000.”

Meanwhile, the rescued migrants lie outdoors and tell their horrifying stories: jails where people have to defecate on top of each other, rapes, kidnappings, people bought and sold, friends getting shot, such as Ulibali Kassim – they say his name out loud so as not to forget him.

The boy with the dislocated pelvis explains how traffickers burned him with a camp stove and threw him out a window. “They wanted me to pay more,” he says.

As the narrative unfolds, the city of Palermo appears. There is a cruise ship docked in the port, white and vast. The luxury vessel contrasts with the faces of the recent arrivals, and speaks volumes about the origin of the problem – the terrible gulf between two worlds that has filled the sea with these flimsy pateras with little to no chance of reaching their destination.

When the Cantabria docks, the first two migrants to disembark are accompanied by police. “People of interest,” they call them. They may know something about the networks.

English version by Heather Galloway.