Elizabeth Subercaseaux, journalist: ‘Pinochet began to cry when we asked him about his lover’

The Chilean writer recounts the ins and outs of her 1989 interviews with the dictator, after his defeat in the plebiscite that would have extended his time in power. ‘He was a very toxic figure… it wasn’t a pleasant experience,’ she tells EL PAÍS

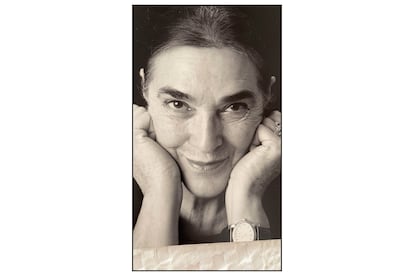

Elizabeth Subercaseaux, 78, is known in Chilean society for her political interviews and her sharp look. She has just published a new book, La Constitución del Golf [The Constitution of El Golf], which is a humorous work, looking at the leadership of the far-right in Chile. Many of these figures live in El Golf, an exclusive neighborhood in the capital of Santiago.

She’s in her house — located on the outskirts of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania — when she takes questions from EL PAÍS via videoconference. During the interview, Subercaseaux reveals the ins and outs of one of the milestones of her career in the 1980s, when, as an opposition journalist, she interviewed outgoing dictator Augusto Pinochet in several sessions. This followed his loss in the 1988 plebiscite, a referendum that, had it been approved, would have extended his time in power even further. Those conversations — carried out alongside her colleague and friend, the late Raquel Correa, an icon of Chilean journalism — were published in a collection in 1989. However, several passages were left out by order of the dictator.

Question. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the coup in Chile. Didn’t you ever think about publishing a book of your unedited interviews with Pinochet?

Answer. In all these years, it has crossed my mind to release the tapes that Raquel [Correa] and I record with him, but they are unpublishable. In general, you cannot release tapes when the interviewee has asked that they not to be published. I always wanted to publish [those interviews], but Raqui didn’t want to. And she died [in 2012]. What I should really do now is burn those tapes.

Q. What was Pinochet like as an interviewee?

A. He was very reactive, because the issue of human rights drove him crazy. He would bang on the table and say again that we were at war [in 1973], etc. Pinochet had blue eyes and when you brought up the subject of human rights, all the nerves in his neck would harden — he would turn red and his eyes would turn yellow.

Q. Did he change over the course of the sessions?

A. No, he was always the same. Pinochet was a very complex person. He had a bit of an old gentleman in him, who treated you [chivalrously]: “I’ll put your coat on for you, madame, let me pull your chair out for you, madame.” He treated women in that sort of way.

Like all dictators, when faced with opposition journalists, the only thing that he was and that we saw was a big liar. His entire government was a lie. [He said that Chile] was at war, when we were not at war with anyone. He said that the Popular Unity government [of Salvador Allende, 1970-1973] was becoming a communist dictatorship. Another thing that struck us was that, within his complexity, he could have been smarter. But he was very primitive, very basic. He struck me as a very cowardly man.

Q. How did you get him to agree to talk to you?

A. We asked for an interview for 15 years. Of course, he always said no. What happened was that Pinochet had a friend — Patricia Guzmán — who had been his cultural attaché in France, and she had been Raqui’s classmate at the University of Chile. They were friends. Patricia knew that we wanted to interview him, and it occurs to me that she must have advised Pinochet to give us [the interview|. We went to La Moneda [Chile’s presidential palace] convinced that he was going to say no to us, because we set conditions [for the interview].

Q. Which ones?

A. The first — which was perfectly stupid — was that only we could record the interview; he couldn’t. The second was that just the three of us [be in the room]. And the third condition — as, of course, we knew he was going to want to revise the text — was that he had to do it with us present. “Why won’t you give it to me?” he asked. We told him that we knew he was going to give it to his wife [Lucía Hiriart] to review; we didn’t want that.

Q. How did he react?

A. He laughed. We also asked Pinochet about his lover. Then, he began to cry. That’s why I say that he was a somewhat complex person. If you had told me before that day that he was going to cry, I would have thought you were crazy. Obviously, he loved that woman, Piedad Noé [an Ecuadorian pianist].

Q. What did you do when he started crying?

A. It was an unexpected and strange moment — we didn’t know what to do. I never imagined that he would react like this. I thought he would get riled up, bang the table or something… But start crying? We waited for him to dry his tears, and then he told us that this couldn’t be in the book. I told him that we would tell [the story] only when he was [deceased].

Q. How did you feel at the end of the five sessions?

A. A very strange thing happened after we finished recording the five sessions: he started calling us. My daughters remember panicking, because he would call at seven in the morning and say: “Hellooo?” [Elizabeth imitates a hoarse and deep voice].

He would say that he had forgotten to tell me something, I don’t know what. We went [to see him] four more times, [unrecorded]. After the book came out, he once summoned me to La Moneda, because he had a problem with [Christian Democrat president-elect] Patricio Aylwin. It was the weirdest thing. Why was he telling me about this? It was never clear to me.

Q. What problem was he having?

A. I have the vague memory that it was a specific problem from those days… He said something like, “you’re a friend of that sector [of society].” He wanted to verify if what the press was saying was true, or something along those lines. What I do remember is that, whatever it was, I told him I had no idea and I got out of there as fast as I could.

Q. And did you talk about those unrecorded interviews with Raquel Correa?

A. Not much, because Pinochet was a very toxic figure, so for us, it wasn’t a pleasant experience. On the contrary, for me, it’s the worst book I’ve ever worked on, hands down. There’s nothing worse than interviewing a lying dictator — you get nothing of value. We arrived with all kinds of documents related to human rights, from the Vicariate of Solidarity [a major Chilean human rights group], but [with Pinochet], it was just lie after lie. When you know that you have to wait 10 or 20 years for the CIA to declassify their documents to find out if Pinochet did or didn’t order the assassination of Orland Letelier [Allende’s former foreign minister, who was killed by a car bomb in Washington, D.C. at Pinochet’s behest], it’s very frustrating. You’re sitting there, almost wasting your time.

Q. What happens to you when you now listen to Chilean politicians defending the coup against Allende in 1973?

A. I find it very sad. I think it was that attitude of the [Chilean] Republican Party that pushed me to write La Constitución del Golf. In the end, humor opens a tremendous window into seriousness. Especially when they say that Pinochet was a great statesman, if only there was another coup...

How can they say that the coup was inevitable? Allende was going to call a plebiscite that same day — there’s a speech he was going to give to ask the country if they wanted him to continue his term, or leave office. Also, there were a series of military coups across Latin America. The coup in Chile began to take shape the day General [René] Schneider was killed [in October 1970]. The coup is a criminal act that gave birth to a criminal dictatorship, which is why one cannot be separated from the other. From the outside, I try to understand what’s happening with the right.

Q. What’s your conclusion?

A. It must be very difficult for the right to get out of a place in which [it has] been an accomplice of a government as criminal as [Pinochet’s]. The baggage they carry is very heavy, so they have to find some way to at least justify the coup, because they’re not justifying what happened next [the numerous human rights abuses].

Q. Has the new generation of the right inherited that emotional backpack?

A. I think that there are young people on the right who don’t hold that position. There are those who wish to appear more progressive. I think Javier Macaya [president of the Unión Demócrata Independiente, or UDI, a center-right party] is quite reflective about what happened [during Pinochet’s regime]. But there are some who are not. When I listen to the Republicans, my hair stands on end, because they’re all justifying the coup. They don’t want to understand that the problem is not the Constitution modified by [former president] Ricardo Lagos, but that it’s the 1980 Constitution [written under Pinochet], which is the genesis [of the current one]. This is why it must be changed, because it originated during a dictatorship.

Q. While moderate rightists were trying to take off this emotional backpack, a far-right group burst on the scene…

A. Exactly. And that’s what my book is about. [During the 2022 national plebiscite, which rejected the text of a new political constitution], the proposal had basically been approved by the left. Now, after the [2023 constitutional council election, which was won by the far-right Republicans], who dares say that this proposal and these amendments don’t have the stamp of approval of the right?

I have no problem with a constitution being acceptable to the right, so long as it includes the entire country. If it’s a good constitution, I hope everyone likes it… including the right, obviously.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.