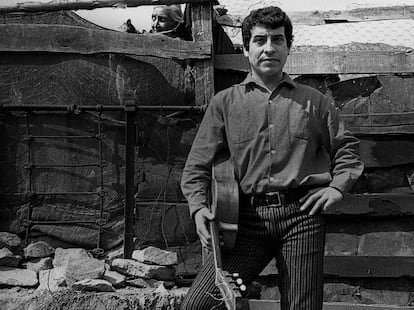

The Víctor Jara case enters the final stage, 50 years after his execution

The Chilean singer-songwriter was arrested on September 12, 1973, one day after Pinochet’s coup d’état. The country’s Supreme Court will begin hearing the case

It’s a coincidence that the judicial case of Chilean singer-songwriter and theater director Víctor Jara’s crime reached its final stage, at the Supreme Court, on the eve of Chile’s commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the coup d’état, on September 11 of this year.

Víctor Jara was arrested on September 12, one day after the coup led by Army General Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990), together with the Armed Forces, which overthrew Socialist President Salvador Allende (1970-1973) and ushered in a 17-year dictatorship. He had gone to the Universidad Técnica del Estado (UTE), where he worked, after hearing a call from the president to defend the government of the Unidad Popular (UP).

In the Chile Stadium, where he was imprisoned, the communist singer-songwriter was tortured and executed together with the director of the National Prison Service, Littré Quiroga. Victor Jara died on September 16. He was shot 44 times and his body was thrown into the street, where it was recognized by passers-by who alerted his wife, Joan Jara. He was 40 years old and had two daughters, Manuela and Amanda.

After a lengthy investigation by Santiago Court of Appeals Judge Miguel Vásquez, seven ex-military personnel have been convicted of the crime. Their sentences have been confirmed, and even upheld, by the Chilean courts. And this week, on Tuesday, the Criminal Chamber of the Chilean Supreme Court will review the case after the defendants, who deny having participated in the murders of Jara and Quiroga, filed cassation appeals.

It is a legal case that began in 1978 when Jara’s widow, with the help of the criminal lawyer Luis Ortiz Quiroga, filed the first lawsuit for the murder of the singer-songwriter in the Fifth Criminal Court of Santiago. It happened in the middle of the dictatorship, with all the odds stacked against her, “at a time when nothing at all was being investigated,” Nelson Caucoto, the lawyer who took up the case 24 years ago and who will argue before the Supreme Court, told EL PAÍS. But, he adds, some progress was made.

For example, starting in 1979, the Chilean justice system sent dozens of requests internationally to interrogate Chileans in exile who had been detained in the Chile Stadium, today named the Víctor Jara Stadium. It was a complex search, because there, in the center of Santiago, thousands of people were imprisoned by order of the dictatorship. The lawyer recalls that it was Joan Jara who managed to locate the witnesses.

Nelson Caucoto has dedicated his entire career, from 1973 to the present, to representing victims of human rights violations of the dictatorship and their families. And it was in 1999, a year after Pinochet was arrested in London on the orders of former Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón and charged with crimes against humanity, that Joan Jara and her daughter Amanda came to his office — a small place in downtown Santiago filled with old files — to ask him to reopen the case. At that time it had been closed for more than two decades without any convictions.

With Chile’s judicial momentum after Pinochet’s arrest, the lawyer requested that the case be reopened. Without pause, Caucoto filed dozens of briefs. “The big question was finding out what the command structure was like at the [stadium], but I didn’t know for more than five years,” he recalls. “We asked the Army, the Air Force, the Navy, the Carabineros, the Investigative Police and nobody knew... It was obvious that there was no interest in investigating.”

The process, once again, slowed down. Frustrated at times, but with audacity, Caucoto thought of another strategy. It happened in 2004, when he asked the military junta that led the dictatorship to testify. Not all its members were alive, but Pinochet was. “That was a turning point,” the attorney says. Although the dictator did not testify — his defense excused him because he had been dismissed in another case (the Caravan of Death), due to subcortical dementia — his request put the Víctor Jara case on the public agenda. Then came a new phase: witnesses appeared in Chile, among them a former conscript who provided key information. “We must have more than 200 statements,” notes the attorney.

The judicial history is much longer and more complex. But, finally, the pivotal moment has arrived, 50 years after the murder of Víctor Jara, and the lawyer is about to deliver the last plea in the case.

For Caucoto, who also represents Littré Quiroga’s family, the fact that the final phase coincides with the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the coup d’état in Chile is “bittersweet.”

“I am ashamed that we had to wait 50 years to learn the result of a trial for a heinous crime. But one must also take into account a series of factors, because the trials in Chile began only in 2000, when human rights judges were appointed exclusively to try these crimes. There was no justice before. There was nothing,” he says.

“Víctor’s was a crime that was designed to never be solved, to be filed in the drawer of some court. That is why it is so valuable that we have come as far as we have. Because, with all the difficulties, if there is commitment from the judges, you can get closure on all the cases,” the lawyer concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.