The private meeting between Kissinger and Pinochet in Chile: ‘We want to help’

Ahead of Henry Kissinger’s 100th birthday, the National Security Archive has published a selection of declassified documents that illustrate the ‘darker side’ of the former U.S. secretary of State

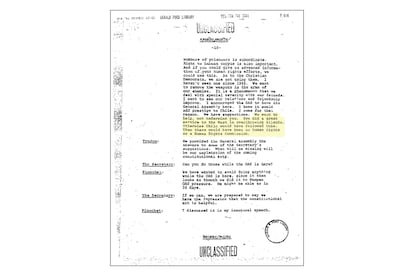

On Saturday, Henry Kissinger celebrates his 100th birthday. To mark the occasion, the National Security Archive, a non-governmental body in the United States, has published a selection of declassified documents that reveal the “darker side” of a figure who was the U.S.’s powerful national security advisor and secretary of state, serving from 1969 to 1977 in the Republican administrations of Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. One of the issues on which the archive places particular emphasis is Kissinger’s role in bringing down the socialist Chilean government of Salvador Allende, and in supporting the military dictatorship led by Augusto Pinochet, who ruled the South American country from 1973 to 1990. Transcripts reveal that, in a private meeting in Santiago in June 1976, Kissinger – whose advisors had recommended he press the dictator on his human-rights violations – backed the Chilean: “We want to help, not undermine you.”

“We are sympathetic with what you are trying to do here,” Kissinger tells Pinochet. “You did a great service to the West in overthrowing Allende.” He adds: “My evaluation is that you are a victim of all left-wing groups around the world, and that your greatest sin was that you overthrew a government which was going communist.” The meeting in Santiago coincided with the general assembly of the Organization of American States (OAS), which was being held in the Chilean capital. Kissinger tells Pinochet he has delayed a speech that he was due to give, in order to warn him that in his address he will refer, briefly, to a report by the OAS’ human-rights commission on the situation in Chile. Kissinger explains that he must do so to avoid the U.S. Congress, where there are “problems” over the issue of human rights, approving sanctions against Chile. “I wanted you to understand my position,” Kissinger says. “We want to deal in moral persuasion, not by legal sanctions.”

During the pair’s conversation, Kissinger urges Pinochet to announce the measures he is taking on human rights, telling him it “would really help.” Pinochet’s first response is that Chile is “returning to institutionalization step by step.” The dictator continues: “But we are constantly being attacked by the [Chilean] Christian Democratics [sic]. They have a strong voice in Washington. Not the people in the Pentagon, but they do get through to Congress. [The diplomat Juan] Gabriel Váldez has access. Also [Allende’s former foreign minister Orlando] Letelier.” Letelier was assassinated by a car bomb in Washington in September that year. U.S. authorities took years to acknowledge that Pinochet had ordered the killing – the first ever terrorist act sponsored by a foreign government in the American capital.

In his meeting with Pinochet, Kissinger tells the dictator that the human-rights announcements he could “use” politically are “constitutional guarantees,” “the precise numbers of prisoners” and the “right to habeas corpus” (the right to be brought before a judge immediately). Kissinger advises Pinochet to announce human-rights progress in packages to ensure they have a better “psychological impact.” To assuage the dictator’s unease about the Christian Democrats, the secretary of state says “we are not using them,” adding that he hasn’t seen one in Washington since 1969. “I want to see our relations and friendship improve,” Kissinger says. “I encouraged the OAS to have its general assembly here. I knew it could add prestige to Chile. I came for that reason.”

In a telephone conversation with EL PAÍS, Peter Kornbluh, a senior analyst at the National Security Archive, describes Chile as “Kissinger’s Achilles heel.” “Everyone is talking about Kissinger’s legacy ahead of his 100th birthday,” says Kornbluh, who has analyzed the documents declassified by the U.S. in 1998, after Pinochet’s arrest in London. “The transcripts of these recordings are his legacy, true evidence of the dark side of his impact on the world. These documents remind us of that. It’s as if we had a fly on the wall listening to what was being talked about.”

At the end of June, Kornbluh is set to release a new book on Pinochet in which he scrutinizes Kissinger’s role in the Chilean dictatorship and, he promises, offers up “numerous revelations.” The former secretary of state’s reputation “is stained in blood from Chile to Cambodia,” Kornbluh says.

The National Security Archive has more than 30,000 pages of transcripts from phone conversations involving Kissinger, many of which he secretly recorded. According to the body, the declassified files leave no doubt as to his role as “the chief architect of U.S. efforts to destabilize” Allende’s government. In the weeks before Allende’s inauguration as Chilean president in November 1970, CIA files reveal that Kissinger supervised covert operations to support a military coup, leading directly to the assassination of General René Schneider, the chief of the Chilean armed forces. One declassified document reveals that on 15 September 1970, Kissinger held a While House meeting on Chile with President Nixon and the director of the CIA, Richard Helms. Helms’ notes from the discussion recall Nixon’s orders to “make the [Chilean] economy scream” and avoid Allende taking office.

Three days after the socialist became president, Kissinger authorized clandestine intervention to “intensify Allende’s problems,” transcripts from a U.S. National Security Council meeting show: “At a minimum he may fail or be forced to limit his aims, and at a maximum [the intervention] might create conditions in which collapse or overthrow might be feasible.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.