The soldier who draws the hardships and hopes of the Ukrainian army from the trenches

‘One day, the artillery fire was so intense, we all thought we would die. But I didn’t stop drawing, it calmed me down,’ says Ruslan Pijota, who has become famous for his comics that portray life on the front

The greater the danger, the more Ruslan Pijota wants to draw. The two months the Ukrainian soldier spent in hospital were the worst. “I thought that rest would help me be more creative, but I missed being in the trenches, being with my teammates, I lacked inspiration.” Pijota was wounded in the leg last December in Bakhmut, the site of one of the bloodiest battles in the war in Ukraine. He returned to the front line with renewed energy. Since then, his popularity as a war illustrator has only grown.

Pijota, 52, is a member of the 113th Kharkiv Brigade of the Territorial Defense Forces. He has served in this volunteer brigade — under orders from the Ukrainian Armed Forces — since February 27, 2022, three days after the start of the Russian invasion. Until the war began, Pijota designed three-dimensional children’s books at a printing press. All his life, he has drawn for fun. “While the rest of the students were studying at school, I was drawing,” he says with a wide smile that never leaves him. On May 6, 2022, on National Infantry Day, his brigade commander asked him for a drawing to commemorate the date. And since then, he hasn’t stopped drawing. Pijota has made more than 100 cartoons, works without artistic pretensions, but of great importance as testimony of the war. Some have been shown in exhibitions, and published in Ukraine’s leading media outlets. But his most important audience is his comrades.

“When he draws, Ruslan discreetly goes to his corner. Then he shows us what he’s done and we laugh, we share it. It is very important for the spirits of the brigade.” That’s according to his platoon commander, who introduces himself by his code name, Major. They have been fighting together since February 2022.

After months of fighting in Donetsk, the army assigned the two last February to a quieter position, on the border between the Ukrainian province of Kharkiv and the Russian province of Belgorod. The interview with Pijota takes place in a maze of trenches, just under a mile from the border. At that distance there is a Russian village, with deserted streets and enemy military units firing artillery. The platoon’s instructions for journalists are clear: in the event of a bombardment, drop to the ground and not enter the surrounding fields because they are full of mines.

In a war, there is lots of dead time, when soldiers see no action. If it doesn’t rain, Pijota’s favorite place is a makeshift table that his unit has cobbled together with planks of wood and ammunition boxes. From there, he sees Russian territory in the distance, and the fields of sunflowers and rapeseed where nothing is grown anymore. He’s completely absorbed as he sketches, oblivious to the clouds of mosquitoes that flutter around him.

Mayor says that his favorite Pijota cartoon is one which features a comrade who died in combat. The soldier was convinced that if he covered himself with an umbrella, Russian reconnaissance drones would not be able to detect him. Mayor and Pijota remember the fallen soldier with a smile full of affection. “The Smakolik camouflage system is the property of the Ukrainian Armed Forces and its export is prohibited,” reads the cartoon drawn by Pijota. Smakolik (“little sweet” in Ukrainian) was the nom de guerre of the dead soldier. “The curious thing is that an umbrella prevents drone thermal cameras from seeing you, that’s a fact,” adds Pijota.

Pijota only saw his family once in the first six months of the war. And since last February, he has only returned home once. His granddaughter was born in this period, and he has not yet been able to hold her in his arms. Even still, he doesn’t stop smiling. His optimism is contagious, though he admits that there are situations that he cannot draw because they stir up too many emotions. As an example, he mentions the day that Russian artillery attacked his position near Bakhmut. A Russian reconnaissance drone appeared to be checking if any soldiers were alive. Pijota played dead, counting every second, until the aircraft flew away.

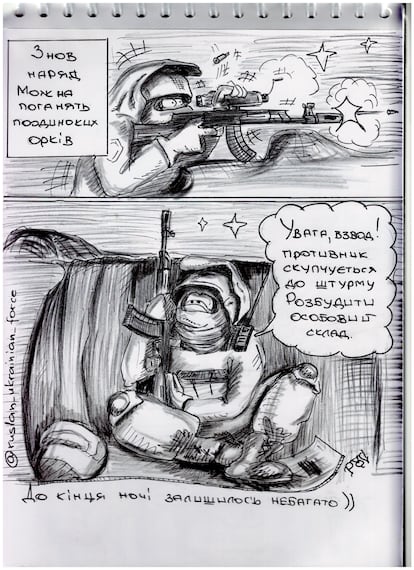

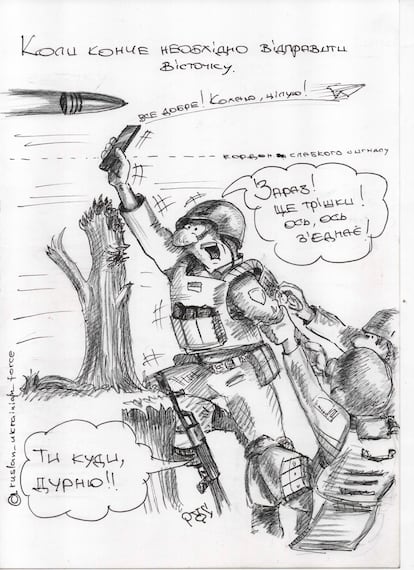

Pijota says that his best drawings happen when he is stuck on his back in the trench while the surface rumbles with explosions and fine rivers of earth fall on his shoulders and the sketch pad. His most productive experience was resisting an enemy siege in Dolina, a town in the Bakhmut region. His brigade had to defend a position in a building. “One day, the artillery fire was so intense that we sincerely believed that we would die. I didn’t stop drawing, it calmed me down,” he recounts. “Drawing helps me psychologically, many people suffer from mental disorders, it helps me stay stable.”

Patriotic messages and satirical scenes

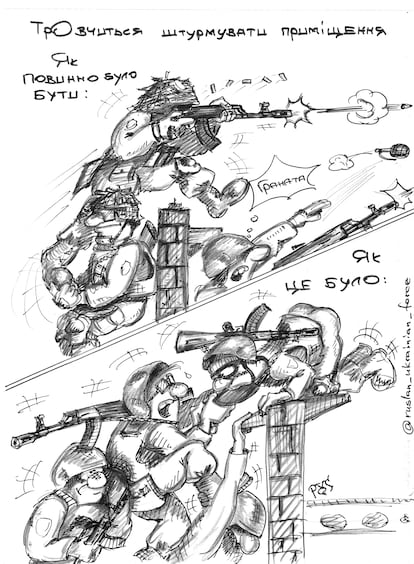

His work is filled with patriotic and heroic messages, but also includes satirical scenes that portray the common miseries of war. In one cartoon, the top half shows soldiers jumping over a wall with the agility of a 20-year-old. The bottom half shows the reality: men from his unit, aged 40 and 50, puffing as they struggle to help one another over the wall.

Some of the characters in the comics appear to have been invented by Pijota, but actually come from real experiences. In one scene, a cow, a pig, some dogs, and a cat are seen following a soldier. “Those animals existed, they went in a group through the Bakhmut area, following the military in the hopes of getting something to eat. It was a very strange gang, but it was real,” says Pijota.

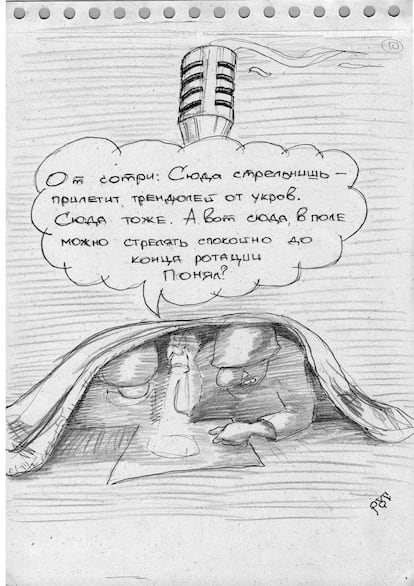

A lot of Pijota’s work also makes fun of and attacks the invader. He says he knows the enemy well because its structure has changed little since the Soviet Union. According to Pijota, it follows the same hierarchical system, the same mentality, has the same equipment and has not tactically adapted. He served in the Soviet Army, between 1989 and 1991, in an airborne regiment: “This helps me understand why they act one way or another, to take advantage of their weaknesses.”

Pijota was also drawing at that time, making caricatures of barrack life and military exercises. “What I did then and now are totally different works, in all respects,” he says. To prove it, he sends 17 digitized drawings of his time in the Red Army. Most are scenes of tension with authoritarian officers and of fear before parachute jumps. There are few signs of camaraderie, a far cry from his current drawings. His style of drawing has also matured. Pijota cites two main influences who helped him teach himself to draw: Ukrainian illustrator and musician Yurii Zhuravel, a contemporary of his, and Albrecht Dürer, the genius of the German Renaissance. “From Dürer, I learned to capture details and use the different shades that a shadow can have.”

Pijota has also drawn how he imagines the end of the war: sitting on a Crimean beach looking at the sea, after liberating the peninsula occupied by Russia since 2014. The soldier appears alone and with his back turned, barefoot, with his boots by his side. “In the war, you always wear boots. So, for me, taking them off would be the symbol that the fight is over.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.