The secret of the six Lucena sisters, the first women in the world to print books

Two U.S. Hispanists argue a Toledo family persecuted by the Inquisition hold the key to the mystery of the most widely distributed work of the Spanish Golden Age: ‘La Celestina’

The six Lucena sisters — Beatriz, Catalina, Guiomar, Leonor, Teresa, and Juana — could have been lost to history, but the bloodthirsty inquisitors had one obsessive habit: leaving everything in writing. In 1485, the Holy Office of Toledo declared that it would offer mercy to heretics who came forward to denounce themselves. The Lucena sisters, aged between 16 and 27, hesitated but ultimately went to beg for penance. They were labeled marranas, hailing from a family of converted Jews, and suspected of secretly practicing their old religion. Teresa and Leonor, still teenagers, admitted to participating in Jewish festivals in their village of La Puebla de Montalbán. Catalina, 25, confessed that she had helped her father in a printing press for Hebrew texts. The Lucenas were likely the first women in the world to print books.

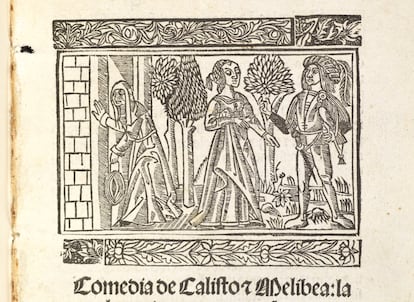

A renowned U.S. Hispanist, Michael Gerli, has now put forward a controversial hypothesis: it was the Lucena sisters who, for the first time, printed the most widely distributed book of the Spanish Golden Age, La Celestina. This work contains a famous hidden message in a poem. If you read only the first letter of each verse, it says: “The bachelor Fernando de Rojas finished the Comedia de Calisto y Melibea [Comedy of Calisto and Melibea] and was born in La Puebla de Montalbán.”

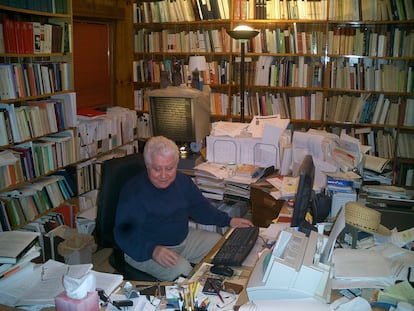

Gerli, professor emeritus at the University of Virginia, recalls reading this work for the first time in 1966 when he was 20. “I was stunned, speechless. I said: ‘What is this! How outrageous!’ It’s a deep inquiry into the human psyche. It’s a revolutionary work that opens up human consciousness with how the characters speak. It reveals hypocrisy, evil, passion,” he exclaims in a video conference from his home in Sonoma, California.

What the young Gerli had just read was the torrential story of Calisto and Melibea, two twenty-somethings who experience uncontrollable sexual desire after Calisto sneaks into her garden searching for a lost falcon. To overcome Melibea’s initial rejection, Calisto enlists the help of a cunning matchmaker, Celestina. The work, written to be read aloud for about nine hours, portrays with sharp humor a gritty world of rogues, lust, and greed, but ends in a heart-wrenching tragedy. After making love in secret, Calisto falls from the garden wall and dies from the fall. Melibea, devastated by grief, confesses to her father that she has lost her virginity, and in her sorrow, kills herself by throwing herself from a tower. The Argentine writer Enrique Anderson Imbert summed it up memorably: “What I admire in Fernando de Rojas is the violence with which he lays bare the world’s desires.”

The book, printed around 1500 as an anonymous comedy, was an immediate success. In just two years, it was expanded and renamed Tragicomedy of Calisto and Melibea, with a prophetic prologue that warned that if 10 people gathered to listen to the story, a dispute would arise between them because each would interpret it differently. The Inquisition was initially slow to react, believing that the lascivious story had a moralizing purpose. However, from 1632 onwards, the Holy Office began censoring some passages deemed blasphemous, such as when a servant asks Calisto if he is a Christian. “Me? I am Melibeo, and I adore Melibea, and I believe in Melibea, and I love Melibea,” he replies. The Church banned the entire book in 1773.

Gerli believes that the legendary first edition of La Celestina — no copy has ever been found — may have come from the Lucena press. Johannes Gutenberg, the German inventor of the printing press around 1450, had revolutionized the printing world, and by 1472, the first book printed in Spain, the Sinodal de Aguilafuente, was produced by printer Juan Párix in Segovia.

At that time, Gerli recalls, La Puebla de Montalbán was a safe haven for clandestine Jewish practice. In nearby Toledo, some 30 kilometers away, a discussion at the cathedral in 1467 led to a mob of old Christians setting fire to the Jewish quarter. A married couple of converts, Juan de Lucena and Teresa López de San Pedro, fled the area with their six daughters. After the death of their mother, the father and orphans settled in two houses, one in La Puebla de Montalbán and the other in Toledo, where they operated a business dedicated to printing Hebrew prayer books.

The street names in La Puebla (currently home to 7,800 inhabitants) seem to tell a story of their own. Walking along Barrio de los Judíos Street, you come to the intersection with Sinagoga Street, where a museum dedicated to La Celestina stands. Every August, the townspeople themselves perform the play in the streets during the Festival Celestina. In a small square, a modest cement statue stands guard over the remains of Fernando de Rojas, the jurist who was born around 1473 and died in 1541 without writing any other books. His name remained obscure for centuries until 1902, when historian Manuel Serrano y Sanz unearthed some manuscripts from the 1525 Inquisition, which confirmed the existence of “the bachelor Rojas who composed Melibea” and revealed that he came from a family of converted Jews from La Puebla de Montalbán.

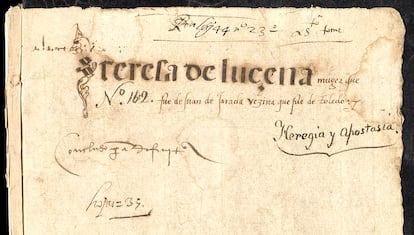

“There were about 2,000 people living in the village, and they must have all known each other,” Gerli says. The main source of information about the Lucenas is the inquisition file on Teresa, who was questioned again in 1530, when she was 62 years old. The document, kept in the National Historical Archive in Madrid, is shocking. The inquisitors detail that the woman was tortured — tied up while half-naked — and sentenced to life imprisonment for, among other sins, having “helped her father make typewritten books in Hebrew” when she was young.

The Lucena sisters shared their fears and sorrows throughout the ordeal. The inquisition process includes a letter from Leonor to Teresa, intercepted by the Inquisition in Toledo in 1510: “Of what, madam, you say that you do not know when it is day or when it is night, I understand you well [...]. My heart is so fallen that I am no longer who I used to be, and you understand me well, and that is why I say no more.”

Another Lucena, Catalina, married a relative of Fernando de Rojas. Gerli makes a bold conjecture. He recalls that the printer Juan de Lucena fled La Puebla for Rome in 1481 to escape Inquisition persecution, leaving his daughters behind. His hypothesis suggests that Rojas later went into business with his distant relatives, the “successors of Juan de Lucena,” and printed La Celestina around 1500 in the already established workshop in La Puebla de Montalbán. This theory has just been published in a volume of studies dedicated to Joseph Snow, the Hispanist who, fascinated by Tragicomedy, founded the journal Celestinesca in the United States in 1977.

Joseph Snow, known affectionately as Pepe Nieves, has been a regular visitor to the National Library of Spain in Madrid for over half a century, always seated at desk 99, surrounded by medieval books and Celestina, without the “La,” as he calls it. “The idea of the possible publication of Celestina in La Puebla de Montalbán needs to be investigated further. Personally, I don’t think it came from that town,” says Snow, who was a professor at Michigan State University until his retirement. This Hispanist even doubts that the young Fernando de Rojas was cultured enough to have authored such an erudite and disturbing text. “The number of people who believe that Celestina was written by someone other than Rojas is constantly growing,” he says.

Most critics, however, maintain that the jurist from the town, Fernando de Rojas, in his twenties like Calisto and Melibea, found some papers with the first act of La Celestina already written and then added another 20, as stated in the preamble of the work. This version is supported by the authors of the monumental 2011 edition of La Celestina, produced by the Royal Spanish Academy under the direction of specialist Francisco Rico.

In the first act that was supposedly found, the diminutives end in -illo, and there are hardly any proverbs. In the remaining acts, the diminutives end in -ito or -ico, and there are many more proverbs. Who, then, wrote this first act in a different style? The leading candidate is the satirical poet from Toledo, Rodrigo Cota (1430-1505), whom Fernando de Rojas himself mentions in his Tragicomedia. Cota also crossed paths with the Lucenas.

Historian Javier Castaño has been tracing the life of this family for over a decade. He says that Juan de Lucena, as a widower, lived with his daughters around 1474 in the modest town of Torrejón de Velasco, now part of the Madrid region. It was here that another converted Jew of the same age, Rodrigo Cota, sought refuge. “Two converted Toledans who meet in a small town would obviously have had some contact,” says Castaño, from the Institute of Languages and Cultures of the Mediterranean and Near East (CSIC) in Madrid. After a few months, the Lucenas moved to La Puebla.

“The key is La Puebla de Montalbán,” says the Italian-U.S. Hispanist Ottavio di Camillo, professor emeritus at the City University of New York. “La Celestina is such a mysterious work... It is a problem that I have dedicated my whole life to and I have not been able to solve. All the answers are hypotheses, but the key is La Puebla,” he insists. “We have a small town lost in the middle of nowhere, with a printing press in Hebrew and women working there at the end of the 15th century. It is revolutionary!” he explains via video conference from his home office in Port Washington.

The two oldest surviving copies of La Celestina are located outside of Spain: an edition printed in Burgos sometime between 1499 and 1502, housed at the Hispanic Society in New York, and a 1500 incunabulum attributed to the Toledo press of the prestigious German printer Pedro Hagenbach, which is kept in the library of the Martin Bodmer Foundation in the Swiss town of Cologny. In this Toledo edition, the acrostic poem containing the hidden names of Fernando de Rojas and La Puebla de Montalbán appears for the first time.

Di Camillo presents an alternative hypothesis, arguing that the Toledo edition is so “replete with errors” that it is “simply inconceivable” for the meticulous Hagenbach was responsible. The New York Hispanicist also does not believe that Rojas was the author, suggesting that he was merely “a young aspiring printer-bookseller” who capitalized on a handwritten translation of a pre-existing Italian comedy for business purposes. In his “plausible conjecture,” Di Camillo proposes that Fernando de Rojas resurrected the old Lucena press in La Puebla to print the 1500 edition, renting printing letters from the Toledo master Hagenbach, which would explain the erroneous attribution. “It is not as far-fetched as it seems at first sight,” he contends in a study published in the same volume dedicated to Joseph Snow.

So, there are now two new theories about what is, according to writer Juan Goytisolo, “the most devastating book ever written in the Spanish language”: either the Lucena sisters, from a converted Jewish family, helped to print for the first time the most widely distributed work of the Golden Age (as argued by Gerli), or Fernando de Rojas revived the old, abandoned Lucena family printing press to produce an astonishing text that came into his hands (as argued by Di Camillo). However, philologist Fermín de los Reyes, author of Incunable. La imprenta llega a España (Incunabula: The Printing Press Arrives in Spain), does not subscribe to either of these theories.

“These conjectures are fine for writing a novel, because they are very nice stories, but they don’t fit with the data,” says De los Reyes, a specialist from the Complutense University of Madrid, who is also familiar with the town of Toledo. His grandparents lived near the Jewish quarter of La Puebla de Montalbán, where Juan de Lucena and his daughters would have had their house-workshop. “They seem to me to be far-fetched hypotheses. I am from a village background, but in La Puebla, there is no record of any printing press since the 1470s. The one in Lucena would have disappeared, each daughter would have led her own life, and there the printing press ended, as it did in many towns. Would it be a nice story? Yes. Would I like it because of my village origin? Yes. Is it highly unlikely? Yes,” he says.

Were the six Lucena sisters, or some of them, the first women to print books in the world, even if it wasn’t La Celestina? Russian academic Shimon Iakerson, one of the greatest specialists in Hebrew incunabula, believes that the printing press of Juan de Lucena and his daughters never even existed. “It is a beautiful myth,” he says, despite the confessions to the Inquisition of several witnesses. Iakerson, from the State University of Saint Petersburg, emphasizes that no incunabulum from La Puebla de Montalbán has ever been identified. In his opinion, the first printer was Estellina Conat, a Jewish woman who printed a work in verse sometime between 1474 and 1478, in Mantua, in present-day Italy.

After more than five centuries, La Celestina continues to provoke debates between people who make conflicting interpretations, as its prologue warned. Michael Gerli takes it with humor. “Sometimes, when I go through Madrid airport, I have to wear a bulletproof vest,” he says, laughing. “It’s part of the joy, the intellectual effervescence of university life. There are people who wish each other a terrible death,” he jokes.

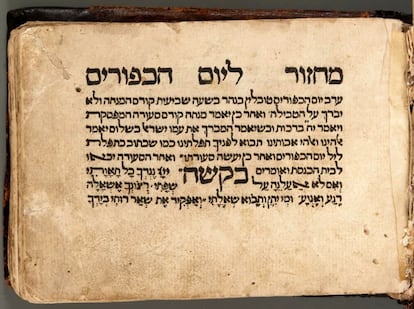

Kenneth Brown, professor emeritus at the University of Calgary in Canada, is convinced that a prayer book preserved at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, printed around 1480, came from the press of Juan de Lucena and his assistants in La Puebla de Montalbán. It is the incunabulum Machzor le-Yom ha-Kippurim, with a strange rectangular format. “In La Puebla de Montalbán, devotional books were printed in Hebrew for the Judeo-Spanish market in Granada,” says Brown. The professor from Canada maintains that Fernando de Rojas was “a type of rabbi in a clandestine Jewish conventicle” and La Celestina is a covert invective against “the suffocating, totalitarian, retrograde and destructive culture” of the times of the Inquisition.

The philologist Amaranta Saguar, from Complutense University in Madrid, has analyzed La Celestina criticism and has detected “a progressive suspicion” regarding this characterization of the historical Fernando de Rojas as a “convert torn between two worlds.”

After an exhaustive review of the inquisitorial process of Teresa de Lucena, the historian Javier Castaño summarizes the facts. A certain Diego Fernández declared before the inquisitors of Seville in 1481 that in La Puebla de Montalbán he had met Juan de Lucena, who was secretly Jewish and made “many Hebrew-printed books” to sell them in the “land of the Moors” of Granada. Two Christian printers confessed in 1485 that they had worked for two years as officers for Juan de Lucena, who had a house in both Toledo and La Puebla and dedicated himself to printing books in Hebrew, surrounded by his daughters. At least Teresa and Catalina acknowledged having helped their father, as Castaño detailed in the book Bastards and Believers.

Castaño dismisses Gerli and Di Camillo’s hypotheses. “I do not believe that Juan de Lucena’s printing press was Juan de Lucena’s printing press,” argues Castaño, in a conscious tongue-twister. “A printing press is a job that involves many people and he did not have the financial capacity to set it up,” continues the researcher, who has searched, without success, for the supposed owner. “If it was not his printing press, it would be difficult for his daughters to inherit it,” he reasons.

Based on the confessions before the Holy Office, Castaño calculates that Lucena, helped by his daughters, could have worked in that printing press between 1476 and 1483, dates that overlap with those of the Italian Estellina Conat. The Lucenas, whether they printed La Celestina or not, were the first women to print books in the world. And the prologue to La Celestina, whoever wrote it, states: “I do not want to be surprised if this present work has been an instrument of struggle or contention for its readers to put them in differences, each giving a verdict on it as they please.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.