Bill Gates: ‘I hope Elon Musk thinks carefully about what he’s saying’

As the new breed of billionaires engages in a mad race to conquer political power and space, the father of Microsoft claims that his foundation is getting closer to finding a malaria vaccine. In his new book, ‘Source Code’, he recounts its first 25 years of life. We spoke to him in California

When Paul Allen encouraged Bill Gates to try alcohol, he got drunk for the first time. When Allen suggested marijuana, Gates gave it a shot. And when he persuaded him to start a company, they founded Micro-Soft — the original name of the software giant that would revolutionize computing. The overwhelming success of Microsoft catapulted Gates to fame in his twenties, turning him into a household name. Since then, he has remained in the spotlight — first as a businessman, then as a philanthropist. Yet, his childhood, adolescence, and early years remain far less known.

A year and a half ago, Gates decided to revisit his past. The result is Source Code, a fascinating memoir that chronicles his first 25 years — from his childhood in Seattle to the founding of Microsoft.

This journey into the past is filled with candid reflections. He recalls being a nine-year-old who had read the entire family encyclopedia from A to Z but struggled to fit in at school, where he attempted to craft an identity as a class clown. He shares memories of his grandmother, Gami, who always beat him at cards. He admits he was a “spoiled know-it-all” with his parents until a psychologist helped him improve the relationship. He describes how, at 13, he gained access to a computer at the same school as Paul Allen, who was two years his senior. He explains how the death of his best friend at 16 left a lasting impact on him. And he reveals that his use of the school’s computer lab nearly got him expelled from Harvard, the elite university he eventually dropped out of to chase a dream that became reality.

The Microsoft founder, who stepped down as CEO in 2006, draws parallels between the software revolution of half a century ago and today’s artificial intelligence era, which he believes will reshape society. At the same time, he expresses concern over Donald Trump’s presidency — he notably skipped his inauguration — and says he hopes to persuade him to minimize cuts to healthcare and green energy.

Gates, once among the world’s richest people, has since slipped in the rankings after donating much of his fortune to philanthropy. He has weathered conspiracy theories, the Epstein controversy, and a high-profile divorce. Now, he welcomes EL PAÍS to a studio at his firm, Gates Ventures, in Indian Wells, California, where he spends part of the winter. An army of assistants ensures everything is perfectly set for the interview. A stylist adjusts his sweater and combs his hair as he poses with practiced discipline. In the waiting room, a deck of cards and a large tic-tac-toe game offer a nostalgic nod to the past he recounts in his book.

Question. Why did you decide to write your memoir?

Answer. I mostly like looking forward and driving the next innovation. But I thought telling the stories of where I was lucky, the key people I knew, and things I’ve learned over time would be fun for me and perhaps valuable for others. It made me appreciate the incredible luck I had: the exposure to computers, being born at the time when the microprocessor would revolutionize things and make computing almost free. Both of my parents, each in their own way, were quite amazing. Then there were people I met in that part of my life: a young friend who died when he was 16, Kent Evans, and another friend from Lakeside, Paul Allen, who helps provide insight about computing. He hangs out and says, “Come on, we need to get something, start a company.” And of course, he co-founds Microsoft with me.

Q, You write: “I wouldn’t trade the brain I was given for anything.” Do you feel privileged by your intelligence?

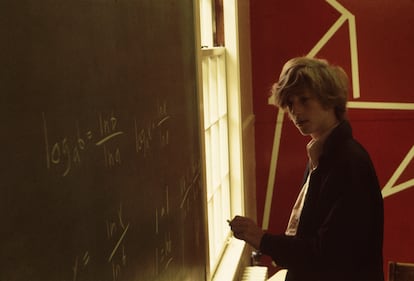

A. I feel very lucky that math comes quite naturally to me, and because of my love of math, many people said, “Come down to this computer and help us figure it out.” Then I found that kind of addictive, because if you get something right, it works, and you immediately find out whether you’re right or wrong. From age 13, until I started Microsoft, I was thinking about software. So yes, the fact that I have a high level of curiosity and persevere to try and make things make sense — which made me a little odd when I was young — has been an incredible strength and key to my success.

Q. At the same time, you mention that if you were growing up today, you would probably be diagnosed on the autism spectrum.

A. There was some frustration where my parents would hear: “Hey, your son is very talented, but, you know, your son is a little disruptive.” Even when I was doing well, like turning in a 200-page report when everybody else turned in a 10-page report, it was like, “Wow, this is kind of embarrassing. Why didn’t I sort of get that I was overdoing this thing?” And it did challenge my parents. In the end, they did a lot of great things. They sent me to a private school where the classes were smaller, and I got a lot of attention. One of the years I was in elementary school, there was a teacher who said I should be pushed ahead even two grades, and then later said, “No, we should push you back a year,” because my behavior in the classroom was… I couldn’t sit still very well. And yet there were some things that intrigued me, where my knowledge was ahead of my age by quite a bit.

Q. Your difficult relationship with your mother led you to see a therapist at a very young age, which was almost unheard of in the 1970s. What impact did that have on you?

A. Nobody got a diagnosis about these neurodiversity issues back then, but it was amazing that they did say, “Hey, go and talk to this therapist.” Most of his customers were couples having difficulties. I was, even for him, kind of unusual. He had me read a lot of books about Freud and gave me some tests and things. Over a period of a year, he really changed the way I thought about my relationship with my parents. He said: “Look, they love you. You have every advantage. You know, if you outsmart them, it’s not impressive at all. You need to appreciate that they’re on your side.” And because he did that in a pretty subtle way, it really did refocus my energy on the outside world and the challenges I faced there.

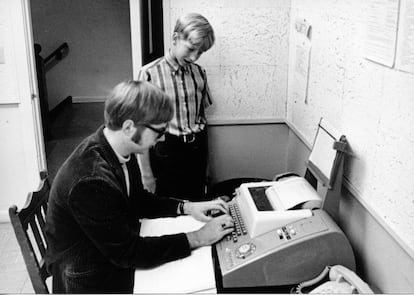

Q. What was it like discovering computers at Lakeside School?

A. The mothers’ club, through a sale’s proceeds, made sure there was a terminal there connected to one of these big computers. That was a very unusual thing, and in fact, the teachers found it confusing. I got drawn in because of my reputation in math, and it ended up being four of us — Paul and Rick were two years older, and then Kent and I in the same grade — who would sit there for hours, trying to figure out what it could do and what it couldn’t do. My first programs were so laughable, just like playing tic-tac-toe, simple things like that, and then playing a more complex game, Monopoly. It turned out that having that skill set at the time when the microprocessor miracle was happening was incredible, and having these friends who did it together.

Q. In your book you describe how you hacked systems to get more computing time. Is there a hacker spirit in every programmer?

A. I’d say a little bit. But in those early days, computers were so hard to get access to that sneaking in at night or finding a way to log in, even if you weren’t supposed to, was the only way we could get computer time.

Q. You also say that, at just 13 years old, during a hike in the Olympic Mountains, you wrote a new version of the BASIC programming language entirely in your head.

A. The area I grew up in has a lot of great hiking. And even though I wasn’t a very good hiker, the camaraderie we had meant we’d often go on these hikes. I was always the one pushing, “Oh, let’s do a shorter hike, not go so long.” But, you know, I enjoyed it. And so, during the hiking itself, my mind could wander and not just think about being tired. I actually did create a piece of the very first Microsoft product, which was a BASIC interpreter. I came up with a very elegant, sort of simple way of doing that, which was very pleasing to me. I find myself four years later actually writing that product, and I’m able to recall, “Oh yeah, I thought this through, you use this back approach,” and it’s super short, and so it ended up being valuable.

Q, How did the death of your friend Kent affect you?

A. Kent was my best friend, and he shaped my thinking a lot. I was kind of lazy about my academics — other than math — and Kent was not. So I thought, “Okay, I should shape up and apply myself in all my classes.” He also got me thinking about what careers were possible — being a general, an ambassador, working in government. He was reading business magazines like Fortune and got me thinking along those lines, which no other kids were doing. He and I talked every night. When he tragically died while learning a bit of mountain climbing, it was a complete shock. Up until then, my childhood had no trauma; it was a wonderful, positive situation. And yet, at that age, you don’t even understand death very well. To make up for that loss, I became a lot closer to Paul Allen. Even though Paul was two years ahead of me, I got him to come back and help me with a school scheduling project, and that deepened our friendship.

Q. In the book, you say that you were nearly expelled from Harvard University and eventually decided to leave.

A. I loved being at Harvard. The classes were super interesting, and I think even what I learned about psychology, economics, and history was valuable to me in my career. I wanted to be a broad thinker. They would feed me. They gave me nice grades. How much better could it be? I was reluctant to drop out, although, in fact, when you leave Harvard, you actually go on leave. So if Microsoft hadn’t worked, I could have gone back. Paul came to pressure me. The key thing was that our insight about personal computing — the last thing we wanted was for that to happen without us. We wanted to be part of it. We wanted to lead the way with software. I had to move to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where our first customer was, and start hiring people and really build Microsoft. So I never got to go back. I don’t recommend dropping out. To this day, I continue to be a student, and as I move into areas like malaria or global health or agriculture, I spend a lot of time and enjoy learning about those things in depth.

Q. You write that you experimented with LSD in the 1970s.

A. I’ve always had an optimistic view of life, not worrying about risks. So when I was young, and Paul said to me, “Hey, try liquor,” I got drunk for the first time. Then he said, “Try marijuana,” so I tried that, too. In the extreme case, he even had me try acid a few times — which, looking back, was a crazy thing to do. I didn’t do it for long, though, because I like my brain to work well, and both during those experiences and afterward, I worried: did I mess up my mind? I wanted to admit in the book that the culture of that time was people experimenting. I think I mostly tried smoking pot because I thought it would make me look cool, and maybe girls would find it interesting. It didn’t work, so I stopped.

Q. You and Paul Allen saw the need for software long before most people understood what software was. How did you recognize that opportunity?

A. It was the combination of Paul telling me about the chip’s exponential improvement, and our exposure to software. If computing was essentially free, there would be so many software things — word processing, databases, spreadsheets — all these things you’d want, and that would be the key factor. So we should build a company that wasn’t just one software product, but actually hired the best people, wrote software development tools, and worked on a worldwide basis. If there was a category of software that was popular, we could compete very effectively because we moved so quickly. Companies like IBM did a lot of software, but they weren’t dedicated to it, so we were much more fast-moving. We’ve gone from where IBM was the giant of the entire computer industry to where it is today. It’s still around, but very small compared to Microsoft, Apple, Google...

Q. How was your relationship with Paul Allen?

A. When you have a co-founder that you’re living with and working with night and day, there’s a certain beauty to it. If one of you is overly optimistic, the other can correct. If one of you is feeling despair over falling behind, the other can pull you back. I was very lucky in those early years — that was Paul. Paul left Microsoft after the first five years or so, and I’ll write more about Steve Ballmer in the next book, because he became my partner in that intense, day-and-night commitment. But Paul’s insights were fundamental. There wouldn’t be a Microsoft without him seeing the potential of the microchips. He moved back to Boston and told me, “We’ve got to go now.” I wasn’t ready at first, but when the Altair, the first personal computer, came out, I realized we had to act or we wouldn’t be at the forefront. Paul and I would agree and disagree about different things. He wasn’t going to go out and hire people like I did, and he wasn’t going to work night and day like I did. But when it came to strategy, he played an equal role in shaping the ideas that led to Microsoft’s incredible success.

Q. What technologies are you excited about right now and how do you think they will transform society?

A. In terms of innovation, there’s more exciting stuff going on today than ever in history, whether it’s in medicine — things like gene editing — or in the computing revolution, where we can understand biology better, so we’re going to get new vaccines. In computing, artificial intelligence is the thing, and I can’t say strongly enough how important that’s going to be. Even though it’s still not totally reliable and we have a lot to do, we have so many smart people and big companies working on this. I see it changing scientific discovery, education, and helping with healthcare, so there’s a lot of good and a lot of change that we’ll have to figure out how to adjust to. But it’s the centerpiece now of everything. Microsoft, Google, and all the top companies are driving toward it.

Q. Would you say that current developments in AI are comparable to the birth of personal computer software in the 1970s?

A. Absolutely, in the sense that there’s a sense of possibility, and AI is going to change all of society. Here, you have hundreds of billions of dollars going into it and millions of people involved. In the early days of personal computing, it was a tiny little business; a lot of the activity was confined to the West Coast, and the machines were so limited that it really took vision to see how you go from something like that Altair to even just what your phone is able to do today.

Q. At the same time, artificial intelligence raises some fears. Do you think they are justified?

A. I realize that as these digital tools have gotten more powerful, it’s not all just good things that come out of it. Until social networking, the idea of word processing and even websites was pretty positive. But now, as we see with social interaction that is stressful for kids, or they’re spending so much time on it that they’re not concentrating on learning the way they should be, I think social networking shows us that humans don’t always take advances and just use them for pure good. Authors like Harari in Nexus talk about when the printing press came along, most of the books were about witches and how you would track down witches, not about the laws of physics. We need to broadly involve society, because AI is way more powerful than social networking, and it’ll be even more important to anticipate and shape how it gets used.

Q. As a teenager, you interned as a Congressional page and showed an interest in politics, but have you ever felt tempted to enter politics actively?

A. When I was young and worked in D.C. at this messenger boy–page sort of job, I got to observe at a very exciting time — 1972, the McGovern–Nixon election. I found it fascinating and said, “Wow, this work is very important.” And yet I never thought I could do it better than others. Unlike the technological thing, where I felt I had a unique understanding and could kind of lead the way. And once I got addicted to computers, that faded away, even though I admire good politicians. We need good politicians more than ever. I spend a lot of time with politicians now because the Gates Foundation needs government foreign aid budgets from the U.S., Spain, and many other countries.

Q. What are your thoughts on Elon Musk, who has taken a very active role in politics?

A. I’m amazed at the number of things Elon’s involved in. I admire the phenomenal work he did at SpaceX to lower launch costs. He did phenomenal work at Tesla to force all the car makers to make really good electric vehicles, which is an important transition for climate. He and I don’t agree on a lot of political things. I thought of him early on as actually fairly progressive and liberal, and now you’d have to say he’s gone more right-wing. I haven’t had a chance to talk to him about that, but given that he’s influential, I hope he thinks carefully about what he’s saying.

Q. Are you concerned about the impact the Trump administration may have on issues such as healthcare, poverty reduction, or the fight against climate change?

A. I am concerned about what their priorities will be. For example, the U.S. is by far the most generous in providing money for HIV drugs that are keeping tens of millions of people alive worldwide. I’m hopeful that this new administration will maintain those programs. I’ve talked to President Trump about that. I’ll be back in D.C. I do worry we have to make the case for this aid money better today than ever. It could be maintained, or it might be reduced, which I would find tragic.

Q. What about climate change?

A. I‘ll be disappointed if they withdraw from the Paris Agreement [one of Trump’s first decisions as president]. There are some innovations going on, new ways of making energy like geothermal. I don’t know how they’ll support those, so it’s another topic that will take me back to the Capitol to meet with the executive branch and Congress, to try to maintain at least some parts of these innovation incentives. I don’t think we’ll have as much focus on climate for the next four years, but I’ll try to minimize that reduction.

Q. How did your early life experiences lead you later to donate most of your wealth back to society?

A. I aspire to my parents’ values. They volunteered a lot of time. They gave, within their income, pretty generously. Also, my friend Warren Buffett is very philanthropic and has talked about how even somewhat limiting the amount of wealth you give to children can be a smart thing. Most of my money will go to the foundation’s work, and that’s my full-time work now. I’m taking the values of my parents and the innovative spirit of Microsoft and applying them to global health for those who are most in need. The progress there has really been phenomenal. We haven’t gotten rid of polio yet, but we’re close. Once we do that, we’ll go after measles and malaria... I don’t think people are aware that global health efforts have actually cut childhood deaths in half, and so this work kind of combines all the lessons throughout my life. I love the work.

Q. You explain in your book that you worked day and night. How has that evolved over the years?

A. When I was young and obsessed with writing code — particularly once we started Microsoft — I worked night and day. I didn’t believe in vacations or weekends. I was constantly trying to move faster than my competition. It was a very unnatural way to live, but it worked perfectly for me in my twenties. Once I got into my thirties, I started taking weekends. I met Melinda, and she told me, “If you want to have a relationship, you need to take vacations.” I chose to make that trade-off. I became very hard-working, just not crazy hard-working. Even today, I obviously have the choice not to work at all, but I still choose to work quite long hours — not like I did even in my thirties. Now, I take vacations, I play quite a bit of tennis, I read books that aren’t directly related to my work. Compared to myself in my twenties, I’m quite lazy now, although compared to most people, I still have a good work ethic.

Q. What advice would you offer to young people seeking an adventure like yours?

A. If someone has a different learning style, I encourage them to think of it as a potential strength. They should find the things that draw them in and help them understand the world in a way that can lead to a great career. I do believe that the digital revolution — now focused on AI — is the most important thing happening today. It’s going to be central to everything. For example, how will we use AI in mental health? We don’t know yet. How will we use it to address polarization and help people see other points of view? We need new ways to bring people together. It’s scary that, even within a country like the U.S., people are not seeing each other with a common view of goals, facts, or mutual respect — things that are essential to a healthy democracy.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.