Ukrainians track Russian missiles on Telegram between beers and snacks

Deceptive tranquility in Kharkiv contrasts sharply with Kupiansk and other war-ravaged towns on the front lines

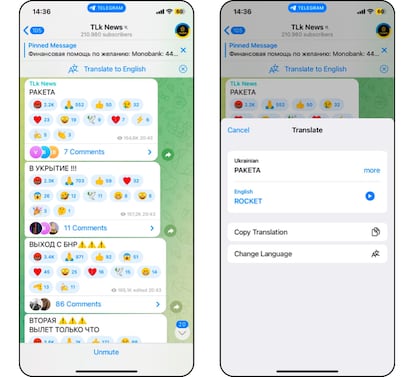

In the Duf Pub, young people drink beer and snack on nachos with guacamole and cheese balls. It’s a normal-looking scene — it could be any bar in Europe. But this is Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city. At 8:43p.m., someone spots a message on the TLk News Telegram channel:

— Ракета [20.43]

Ракета means rocket. TLk News has just posted a warning that a Russian rocket aimed at Kharkiv had just been launched. Three or four minutes later, an explosion boomed. The people in Duf Pub paise for a moment, and then continue eating and drinking as they monitor Telegram. A rapid series of messages in all caps pops up.

- GO TO SHELTER [20.43]

- FIRST MISSILE [20.43]

- SECOND MISSILE NOW [20.45]

Another explosion. Lera, a 21-year-old, nervously sips her wine. She lives in Kyiv and is visiting her boyfriend in Kharkiv. Since the capital is farther from the Russian border, they have more time between the warnings and the missiles strikes. But Kharkiv is barely 18 miles (30 kilometers) from Russian positions, and everything happens quickly here.

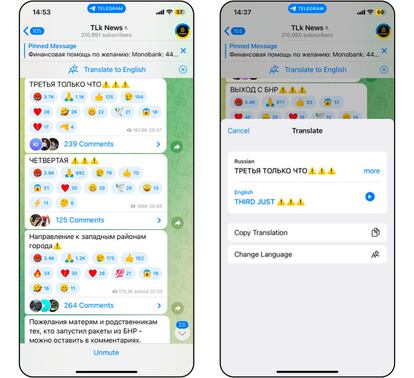

- THIRD ONE JUST LAUNCHED [20.47].

- FOURTH [20.49]

- TARGET AREA: WESTERN DISTRICTS OF THE CITY [20.50]

The Duf Pub is in the center of the city, which is somewhat reassuring. But not entirely. More messages are posted on the Telegram channel and they are always accurate. Each warning message is followed by a boom. People start leaving the bar. Those on foot with no ride home wait a little. Some look tense, but many others seem calm. People with cars, like Lera and her boyfriend, drive home at full speed. The city buzzes with cars going as fast as they can, like the military vehicles do when traveling over dangerous roads – it’s the safest way to go.

At 3:35am, a reassuring message is finally posted:

- NO MORE LAUNCHES.

The air raid sirens don’t sound again until six in the morning. Like many other Telegram channels around the country, TLk News is run by civilians with information from military intelligence sources.

Local authorities confirmed the six missile strikes without providing many details. No injuries are reported, but they only do this when there are civilian casualties. The rockets were S-300 anti-aircraft missiles, defensive weapons that Russia is using to attack ground targets because of an arms shortage. Since they are less accurate, the S-300s can cause more collateral damage and civilian casualties. The worst carnage inflicted by this type of missile happened last September in Zaporizhzhia, when they struck a civilian convoy, killing 32 and wounding 100.

Kharkiv is Ukraine’s second-largest city, with 1.5 million inhabitants before people began evacuating after the invasion. This heavily battered city was a flourishing academic, cultural and industrial center just a year and a half ago. At first glance, it still seems like a normal, peaceful place. The hustle and bustle around the Nikolsky Mall is astonishing — almost every shop is open with clothes, food, electronics and perfume for sale. The mall’s mini indoor soccer field is crawling with kids kicking a ball around. Fifteen days after the Russian invasion started, a bomb struck and damaged the building, but it was immediately repaired, like so many other places around the country. Life goes on.

Young people get all dressed up to stroll around Kharkiv, just like anywhere else. But a closer look at these streets reveals a distinct reality. Broken glass, boarded-up windows and bomb-damaged buildings expose the hell that the city has experienced as its citizens try not to worry about the constant threat of the nearby invaders. When violence is part of everyday reality, people tend to block it out.

Kupiansk – in the red zone

With a front line so close, violence is around every corner. About 50 miles (80 kilometers) from Kharkiv is the town of Kupiansk, with 30,000 pre-invasion residents. Kupiansk is in the red zone, just six miles (10 kilometers) from Russian positions. The town’s former mayor rolled out the red carpet for the Russians, who occupied the city days after the invasion started and made it an operations base for the next six months.

Ever since Ukrainian forces pushed the Russians out of Kupiansk last September, the town has been hit by a never-ending shower of missiles. The rumble of explosions is non-stop and destruction is everywhere: the market, courthouse, apartment buildings, hospital, cultural center and even the soccer stadium. The Russian artillery batteries are six miles (10 kilometers) away.

One of the most recent targets was Kupiansk’s history museum, where photos of local World War II veterans still hang on the dusty walls amid the rubble. They represent the Soviet imperialism that surged in the post-war period and faded with Ukraine’s independence in 1991. The war in Ukraine hasn’t achieved Russian President Vladimir Putin’s goal of restoring the empire. Instead, the war is burying Putin’s dream — every bomb is another brick in the wall between the two countries.

“This is how Russia values the culture of the USSR,” laments one of the museum workers carefully, removing everything that can still be used. One of them smiles and plays a few notes on a piano amid the rubble while others dust off a 1985 calendar, books and posters. After the attack on the Kupiansk museum, President Volodymyr Zelenskiy told the world Russia has bombed 60 museums and art galleries all over the country — a cultural heritage obliterated.

“We had just watered the plants and turned on the computers when we heard an explosion. Everyone ran, and I fell down,” said Svetlana, a 55-year-old museum employee who asked us not to use her last name. That April morning, panic gripped the 15 museum workers trying to escape the missiles. Two died that day — museum director Osadcha Irina Anatoliivna and her assistant, Olena.

Svetlana tells about the attack as we stand in the city’s stadium, where a bomb ripped open an enormous crater in the field. Svetlana and her co-workers spread some books and documents salvaged from the museum on the partially destroyed stands to dry. One book bears the undaunted face of Vladimir Lenin.

Kupiansk was liberated by Ukraine last September, but peace has not returned to the town. Life lurches on in fits and starts. The demolished local market has been replaced by street vendor stalls, and residents line up every day for humanitarian aid. Others wait for the hot meals cooked by an organization established by Spanish celebrity chef, José Andrés. On the menu today is borsch soup, macaroni and beef. It smells good.

The mayor in the bunker

Northeastern Ukraine is critical to Ukrainian forces fighting to break Russia’s grip on Luhansk in the breakaway Donbas region, coveted by the Russians for its mining and industrial resources. Kupiansk Mayor Andriy Besedin explains the area’s strategic value from a bunker where they recently moved the municipal offices. They have to relocate every few days to avoid detection and shelling.

“Kupiansk is a major railway hub that connects the Donbas to the rest of Ukraine,” said Besedin, making it crucial for the recovery of areas liberated by the counteroffensive. “When they [the Russians] withdraw, we will have to transport a lot of aid, construction materials and humanitarian relief through here to save lives and help people survive. Kupiansk will be a strategic point for logistics and communications.”

Kupiansk has another key national security function in the counter-offensive — detecting Russian collaborators. Besedin told us there is a “screening center” in the town of Shevchenkove, an administrative building where Ukrainian intelligence personnel interview anyone arriving from the occupied territories.

“Many people leave or enter Kupiansk every day and they must pass through these checkpoints,” said Besedin. “Sometimes people disguise their identities, but after they go through the checkpoints 10 or 11 times, we always end up identifying those who are aiding the enemy.”

Since Ukraine is a constitutional republic, Besedin says it’s up to the judicial system to determine who is working for Russia. But he exonerates all the civil servants and doctors who remained behind during the occupation to provide public services. People like Svetlana Tsiba, a civil servant from the village of Grushivka, next to Kupiansk. Ukraine’s security services (SSU) interrogated her for 24 hours in the Shevchenkove screening center to find out why she stayed in her post during the Russian occupation. She was later released based on her own testimony and the many Grushivka residents who vouched for her.

On the outskirts of Kupiansk, near the eastern bank of the Oskil River, firefighters arrive in the just-bombed village of Petropavlivka. Just three miles (five kilometers) from the front lines, the village is almost completely deserted. The firefighters spot a plume of smoke rising from the bomb site — a house in ruins. The family that lived there left a few weeks ago, so there were no casualties. “I heard a cracking sound, a loud and terrible cracking sound,” said a tearful Maria Nikolayevna, an elderly woman who lives in a nearby farmhouse with her daughter, who is battling cancer. Unlike most people, she has no plans to leave, despite the harsh reality of life in wartime. “How am I going to wander around the world at my age?” she asks.

Credits

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition