Salman Rushdie: ‘My story is about beauty facing death’

The author presents his book ‘Knife’ at the Hay Festival in Cartagena. He reflects on the attack he survived in August 2022 and his refusal to interpret it through pain or anger, arguing ‘that would be the end of my life as a writer’

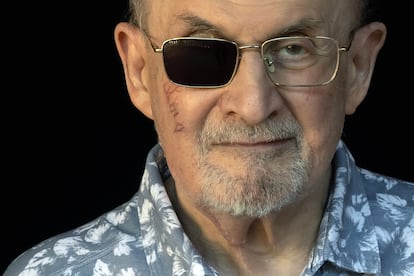

Wearing a black patch over his right eye, Salman Rushdie walked onto the stage at the Cartagena Convention Center in Colombia for the 20th edition of the Hay Festival. The famed author and essayist was a guest of honor of the festival in 2009 and 2018, but had never come to the event to talk about how close he came to death.

In 2022, Rushdie, who had been receiving death threats since 1988 after publishing The Satanic Verses, was the victim of an attempted murder that he narrowly survived. “One of the great public intellectuals of our time… and he has paid a price for it,” said Colombian novelist Juan Gabriel Vásquez, introducing him and his latest book, Knife, which details the attack.

It all unfolded in August. Rushdie was about to begin a talk in a small town in New York State when a man in the audience attacked him with a knife, stabbing him a dozen times, the blade of which Rushdie never saw. “But I felt it… it was an attack that lasted half a minute,” he told Hay Festival. The audience, however, did not remain passive — they rushed to save his life, and it is to them that Rushdie feels the deepest gratitude. He also expressed his thanks to the audience in Cartagena, with a touch of humor.

Rushdie could have kept his story to himself, letting it remain confined to personal diaries rather than turning it into literature. But silence was never his style. “I didn’t want anyone else to tell my story, I wanted to tell it my story. Most writers’ stories aren’t all that interesting — maybe some alcohol problems, the usual stuff, nothing more,” he said, laughing.

When planning his book, he considered visiting A — as he refers to his would-be killer — in prison. However, his wife cautioned against it. “Besides, I thought, if I meet him, I don’t think I’ll learn anything good from him. I might just hear some predictable clichés about that person, but I’d rather imagine him myself — maybe I can picture him in a more compelling way. So, I made him up, which for me was a form of revenge,” he added.

There was one thing Rushdie knew about A. He was a 24-year-old Lebanese man raised in New Jersey. “In an interview with the New York Post, he said he hadn’t read more than two pages of what I’d written,” Rushdie recalled. “I read in the paper that the last thing he did before attacking me was cancel his gym membership. I guess he knew I wasn’t coming back anytime soon.”

Rushdie did not want to merely tell the story of the attack against him. He wanted to explore a deeper narrative — a triangle between himself, death, embodied by A, and a third character, beauty. “This is a story about beauty facing death,” he said. The book, he explains, is about love as an antidote to death — love, for example, for his wife, who “also gave me the strength to write.” He did not want it to be a book about fear or rage, “because that would be the end of my life as a writer.”

Many questions linger from the attack — more emotional or existential than legal. Rushdie still wonders about his survival, like a non-religious man who’s been told by doctors that he’s miraculously alive. “But I don’t believe in miracles,” he insisted. “The knife in my eye hurt my optic nerve, which carries information to the brain, but fortunately, the attack didn’t touch my brain. Just touching it a little would have had incalculable consequences, so the good fortune I have is that I still have my brain,” he said.

He also wonders why he didn’t fight A off, why he didn’t resist when the attack came. “I was very upset by that paralysis. When violence comes suddenly, you don’t know what to think, what to do. I think that many people who experience that intrusion of violence in their lives can recognize that emotion.”

If there is a religion that Rushdie believes in, it is the sacredness of books. He recalled a meeting he had a few years ago at Google’s offices in the United States, with 23-year-old readers, technology enthusiasts, to discuss “how sophisticated book technology is.” Books do not easily lose their data, their pages dry out if they fall into water, and an entire section doesn’t vanish the way it might on a computer. “Who uses a fax machine today? Much of its technology becomes obsolete, but the book has been around for centuries and is not obsolete,” he said.

The conversation with Vásquez, in which Rushdie only tangentially mentioned Elon Musk and far-right fanatics, paused momentarily when they turned to the Nicaraguan crisis. Rushdie shared that he met Nicaragua’s current president, Daniel Ortega, years ago when Ortega was a guerrilla fighter opposing the dictatorship, not the authoritarian leader he is today. “Now I see what Daniel Ortega has become, and I find it tragic,” said Rushdie.

Rushdie had interviewed Ortega but knew the conversation would be awkward if a tape recorder were placed between them. So, he cited a stomach ache and went to the bathroom every 15 minutes to take notes. “I also interviewed Violeta Chamorro. I did record her, thank goodness, because she told a lot of lies,” he said. “I also had hope for the Sandinista revolution, and it is very tragic that Daniel Ortega has become worse than [Anastasio] Somoza. That is what happens with revolutions. Khomeini’s revolution became worse than the Shah’s.”

Such revolutions, Rushdie argues, endanger the words of a writer who has poured his life into his work, highlighting love and beauty more than those who seek to destroy literature with a knife.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.