Salman Rushdie: ‘I would rather not have to live under threat, but I would absolutely not change a single thing’

The esteemed writer, who was attacked on stage six months ago, talks to EL PAÍS about his recovery, writing influences and new novel, ‘Victory City’

Last August 11, moments before Salman Rushdie was about to address an audience of more than a thousand people at the Chautauqua Institute in New York State, a 24-year-old religious fanatic named Hadi Matar rushed up to the stage and stabbed him 15 times. The presenter of the event, Henry Reese, immediately jumped on the attacker, suffering his own wounds while likely saving Rushdie’s life. A state trooper who was present managed to restrain the assailant, handcuffing him, while four doctors who happened to be in the audience were able to stanch the writer’s bleeding until emergency medical services arrived.

Rushdie, who remained conscious but uncertain of what had just taken place, wailed from the pain caused by the violent wounds. Everything happened in a matter of minutes. The emergency medical services diligently took over and a helicopter transported the author to a medical center in Eire, Pennsylvania, where surgeons were able to maintain Rushdie alive. His fifth wife, the poet and novelist Rachel Griffiths, rushed to be by his side. Some agonizing days followed, during which there were fears that he might not recover, but after six weeks, he was released from the hospital and returned home, where his slow recovery continues through continuous medical care.

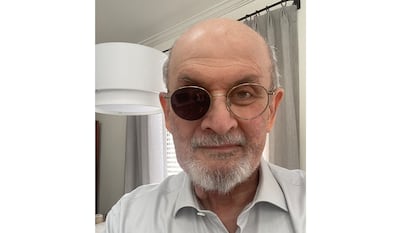

The author agreed to speak with EL PAÍS on the occasion of the publication of his new novel, Victory City, an epic recounting of the Vijayanagar empire in southern India from the 14th through the 16th centuries. The conversation took place over Zoom. When his face appears on the screen, the grim consequences of the attack are evident. He wears glasses, one lens completely black to cover the socket of the missing eye that he lost in the assault. There is a scar on one side of his face, almost imperceptible, and another on the left corner of his lips, which has not affected his speech. He seems at peace, but his voice is more subdued than usual, and he has not lost his subtle sense of humor and at times smiles. He wears a short sleeve black T-shirt. Behind him a bookcase, a chimney, and a printer disappearing into the shadows.

Question. How are you feeling physically and psychologically six months after the assault?

Answer. I’m not completely recovered. I get tired, but I’m healing, and psychologically improving. I haven’t come out of the tunnel yet, but I will.

Q. Are you writing?

A. Very little, but new ideas are coming to me. I hope that my brain will find a way to recapture the mental habit essential for writing, but that hasn’t happened yet.

Q. Are you sleeping well? Do you suffer from nightmares?

A. At first, there were a lot of them, but now not as often.

Q. Is it true that a couple of days before the incident you dreamt of someone attacking you with a sharp object?

A. Yes, that’s true.

Q. Do you believe in the prophetic power of dreams?

A. Not really, not in a literal sense. A bizarre coincidence. It wasn’t anything like what actually happened. Someone was attacking me with a kind of spear.

Q. There has been an overflow of affection and sympathy for you after the attack. Was it different than what happened after the announcement of the fatwa?

A. There were marked differences of opinion in the press then, but now the support has been unanimous, maybe because I was actually hurt.

Q. You have always been a champion of freedom of expression, with a leading role in organizations such as PEN’s World Voices Festival and Cities of Asylum. But writers remain under threat.

A. Sadly, that is the case. Through my work at PEN and other organizations I know that there are many writers all over the world living under danger and in need of protection.

Q. What is Cities of Asylum?

A. It’s an organization that offers protection to writers that need it all over the world. Now it is known by the acronym ICORN [International Cities of Refuge Network]. The headquarters are in Norway. I am very proud to have been one of its early promoters.

Q. The person who was introducing you on the day of the assault, Henry Reese, is a representative of the organization.

A. Right. In fact, the event wasn’t even about me. It was in support of Cities of Asylum. The ironic part is that during a discussion meant to shed light on writers under threat such an attack on a writer would take place.

Q. Do you regret anything that you have written? If you could go back in time, would you change anything?

A. I would rather not have to live under threat, but I would absolutely not change a single thing. In a way, the question is unnecessary, because since the fatwa was announced when I published The Satanic Verses, my fifth book, I have written 16 books, and I am very proud of that. I regret nothing.

Q. How did you conceive The Satanic Verses, under what circumstances?

A. Sorry, I don’t want to talk about that.

Q. What would you consider the primary throughline of all your novels?

A. My life. My books reflect the different states of consciousness through which I have gone at diverse periods in my life. With the passing of time, your ideas and your relationship to things change. Also, there’s physical change. I’ve moved from countries twice, first from India to England, then from England to the United States. That has shaped my books, which make up a truer autobiography than if I had written one literally. My books are the autobiography of my imagination.

Q. There is another thread that runs throughout your books, and it is the manner in which you handle the fantastical. How do you characterize that?

A. If I look at the Western tradition, I feel close to writers like Bulgakov and Kafka, and also to the American fabulists of the 1970s, such as Pynchon, who was a great influence when I was young.

Q. Your work is unique in the sense that it blends diverse literary traditions from Eastern works such as A Thousand and One Nights, the Ramayana, and the Panchatantra, to Greek mythology, to some of the biggest names in the Western canon, like Chekov and Conrad, whose first names you used in the title of your memoir, Joseph Anton. And then we have to add a long list of others, such as Kafka, Mann, Joyce, Calvino …

A. And the tradition of the Indian novel, which is relatively young at 150 years or so. In Victory City I create a fictional space following in the footsteps of R.K. Narayan, who invented the fictional city of Malgudi. The city in my novel is Vijayanagara. These are imaginary places, such as Garcia Marquez´s Macondo and Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha , but they are in fact more real than those that exist geographically.

Q. How did the novel develop?

A. It took me three years to write. I spent a lot of time reading about the period, about the entire history of an empire that lasted 250 years. It took off when the protagonist, Pampa Kampana, appeared to me one day, and said, “I will live 250 years and tell the story.”

Q. Appeared how? What do you mean by that?

A. I didn’t have the slightest idea that she would be there, and one day, there she was, right in front of me. I woke up and looked at the very same screen I am looking at now as I chat with you and saw her as clearly as I see you now. And then she said “Pay attention and I will tell the story.” So I paid attention.

Q. The buzz for the book before its release is tremendous and the reviews have been excellent.

A. I’m very moved. This one has become more important than the others because of its release after the attack that I suffered, but I don’t want it to be judged in light of that, but instead for any literary merit it may hold.

Q. The novel is a meditation on the role of fiction and the power of the word.

A. Yes. The title is a translation of Vijaynagara, Victory City, but the novel itself is a city of words, and words are the things that triumph, which is one way to suggest that language creates the world. At the beginning of the novel, Pampa says that she is author of an imaginary text that she will bury as a message to the future and that it will not be read for 450 years, or during our time. The language recreates the city through the words of the narrator. The intent is to suggest that the art of language creates the world, in a very literal sense.

Q. The protagonist is a woman who lives 248 years during which she witnesses countless historical changes. It’s impossible not to think of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando.

A. The wonderful thing about literature is that nothing is ever truly new. Everything has been done before. I have great admiration for Woolf. Her best novel, I think, is Mrs. Dalloway, which I re-read often. Orlando is an extraordinary text that I must have had in mind and no doubt influenced me.

Q. Another obvious influence is Italo Calvino.

A. Of course. There is a section of the book that is a pastiche alluding to Invisible Cities, in which two characters describe two imaginary cities that bear their names, and that I add to the list invented by Calvino. I was fortunate to meet Calvino when I was young, and he was always very encouraging. As a matter of fact, when Midnight’s Children was published in Italian, he wrote a very lengthy review. I met with him many times, and after his death I continued to see his wife and daughter. I was also lucky enough to meet E.M. Forster when I was in Cambridge. He was very endearing and accessible to students.

Q. During the pandemic you wrote a play about Helen of Troy.

A. I’ve always been fascinated by Greek tragedy, and the character of Helen has always intrigued me because everyone knows who she is, but in fact she is like an empty space. Nobody has treated her as a character in her own right, so I decided to fill the vacuum. It’ll be produced in London early next year. To make things more difficult to myself, I wrote it in verse. I’m no poet. I’ve published one poem in my entire life, but the play about Helen is 90 pages of iambic pentameter.

Q. Do you think that you will write about the recent attempt in the way that you wrote about the years after the fatwa in Joseph Anton?

A. Maybe, I’m thinking about it. Not like in Joseph Anton because that book covers more than a decade of my life. It’s my longest one. This would be different. This is something that happened, and if I write about it, it would be about what something like this means for me as a human being. Are there larger issues behind the act that almost took my life, any repercussions beyond myself as an individual? I don’t have the answers to that yet.

Q. You have always been a very vibrant and optimistic person. Are you facing the future with hope?

A. I narrowly escaped. That question makes me think of something Woody Allen said when they asked him if he was glad that he would live on in his movies after his death, to which he responded that he would rather live on in his apartment. [Laughs]

Q. Going back to where we started. Have you been able to write at all?

A. In the last six months I have not written a single page that I can use.

Beyond 'The Satanic Verses'

The assassination attempt in August gave rise – aside from worldwide disgust – to a wave of sympathy for Rushdie, with gestures of support from all over the globe. The most memorable of those was conducted on the steps of New York Public Library, in the city that the writer made his own when he believed that the fatwa ordered after the publication of The Satanic Verses had been forgotten. The novel was considered blasphemous to Islam by the ecclesiastical powers of Iran. He was wrong about the forgetting.

Six months ago, a radicalized Lebanese-American believed it was his duty to carry out the old sentence. After spending the previous night outdoors, he bought a ticket for the presentation, rushed onto the stage, and brutally stabbed the writer. Beyond The Satanic Verses, Rushdie is one of the greatest living writers in English. Among the best of his work, to which Victory City can be added, are the following books.

Midnight’s Children. Rushdie’s best novel, which fuses with an effortless grace the novelistic traditions of East and West.

Haroun and the Sea of Stories. A novel inspired by the fabulist Indian tradition that he wrote for his ten-year-old son.

Joseph Anton. A chronicle of the years that he lived in hiding in London, protected by Scotland Yard is a fascinating portrait of this period in his life.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.