China plays geopolitical chess game in Latin America

A fragmented and polarized world is living through a strange scenario, in which a single power no longer has total hegemony. Central and South America must now navigate this new political climate

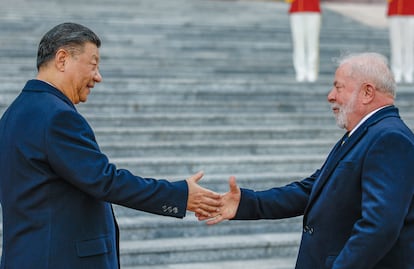

The international agenda in Latin America has been unusually intense in recent weeks. Brazil’s President Lula da Silva visited China; Colombia’s Gustavo Petro met with Joe Biden; Russian leaders met with counterparts in Brazil, Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba; Iranian officials toured the region, with a special stop in Caracas; and the foreign minister of India traveled to Guyana, Panama, Colombia and the Dominican Republic. To this list we must add the recent change in position of Honduras vis-à-vis Taiwan – which is progressively losing allies in the region – and, in 2022, Turkey’s foreign minister visited six countries in the region.

These apparently isolated events actually had a common thread – in global politics, there are hardly any coincidences. The activities of China, India, Russia, Iran and Turkey in Latin America are, in fact, part of a comprehensive project meant to strengthen their presence and renew alliances.

At the global level, we’re observing seismic movements that are redefining the concept of power, which generates intense debates for its definition, but consensus regarding its intangibility and difficulty of measurement. Analysts such as Moisés Naím, of Venezuela, think that the concept considering the emergence of new actors that that challenge it and make it increasingly weak, transitory and restrictive. Changes in the international economy, politics, population, migration patterns and the emergence of new technologies are also factors that have also contributed to the breakdown in traditional power structures. For his part, Richard Hass – president of the Council on Foreign Relations in New York – opines that power has spread to a greater number and variety of actors, which has led to changes in global governance. For this reason, he asserts that “the question is not whether the world will continue to collapse, but how fast and to what extent.”

The international system is marked by fragmentation, conflict and polarization. The bipolar scenarios, or the hegemony held by a single power, are in the past. We’re facing the emergence of new players, ideas and global interests, in the midst of new competitions and tensions. In other words, we went from the Cold War to the Cold Peace. The correlation of forces on the global chessboard has changed remarkably, according to former Colombian Foreign Minister Guillermo Fernández de Soto.

The new axis of power is leaning from the West to Asia. By 2060, the latter will hold more than 55% of global GDP, 5.3 billion people, an enormous middle class – north of 80% of the population – and will have gone through an unparalleled process of urbanization and the construction of megacities, with six of the 10 largest metropolises in the world being in Asia.

The aforementioned reality will lead to the abrupt movement of geopolitical pieces, which will have profound effects in Latin America – a region that was, historically, in the USA’s sphere of influence. However, this phase of Washington’s hegemony in Central and South America is coming to an end. A new era is being reconfigured, in which the US will maintain considerable strength – at least in economic and military terms – but its influence will be greatly diminished.

Strategic competition scenario

We are now facing a strategic competition between the United States and China, which is accompanied by revisionist actors such as Russia and Iran. This newfound dynamism and competitiveness is transforming the international political economy. Additionally, there’s a rivalry between two models: liberal democracy and the market economy, versus illiberal democracy and state capitalism. It’s a scenario that presents conflicting views on how to organize society and construct a new order of international relations.

For some Latin American countries, this is an opportunity to exercise their sense of agency, marked by the search for greater autonomy in North-South relations, especially in key areas such as diplomacy and trade. For many governments in the region, the so-called “Chinese development model” has become the way forward, without taking into account its predilection for autocratic regimes and the collateral effects on democracy, institutions, the rule of law and individual liberties.

In this new cycle, the “Dragon” – as a new world power and one of the locomotives of economic growth – has launched a diplomatic offensive throughout Latin America, in an increasingly open, active and contestatory manner. The stealth and discretion that once characterized it are a thing of the past. China has openly invited strategic partners in Central and South America to join its Belt and Road Initiative, Global Development Initiative and Global Security Initiative. China’s new partnership with CELAC – the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States – has acquired special importance in its relationship with the region.

Beijing’s initial approach has had a particular emphasis on the economy, with the intention of obtaining natural resources and primary goods, as well as opening new markets in the region that are crucial for the growth and stability of the Chinese economy. The result has been that bi-regional relations have deepened. China has become South America’s first trading partner and the largest source of financing in the energy, infrastructure and space industries, with more than 2,700 China-funded companies operating throughout the region. This has contributed to the displacement of the United States and the marginalization of other parties, such as Japan and Europe.

The Chinese government’s offer of large loans for infrastructure projects has been a constant in the 21st century. The conditions, benefits and long-term impact of these loans are a matter of debate. Currently, however, there is a special emphasis on investments in the fields of innovation, technologies, telecommunications, smart cities, as well as the transfer of ideas and the internationalization of the Chinese yuan.

Experts have pointed out that Latin American governments are entering new dependency relationships, which will replicate political, commercial and financial patterns of the past. This could generate development traps, mainly linked to growing external debt. One recalls the experience of African countries, in terms of the de-industrialization processes faced and the damage caused in the realms of social stability, according to the recent book China and Latin America: Development, Agency and Geopolitics by the London School of Economics (LSE)..

Beijing has also expanded its diplomatic, cultural, scientific and military presence in the region with great pragmatism, within the framework of so-called South-South cooperation and with an emphasis on the use of “soft power.” There have been 13 visits by President Xi Jinping to the countries of the region. The Confucius Institute is present in 23 Latin American countries – with the aim of bringing language and culture closer together – while “vaccine diplomacy” was launched during the pandemic. Taiwan has also been isolated in the hemisphere thanks to China’s actions, with the governments of Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, the Dominican Republic and Panama breaking relations with the island in favor of Beijing. Arms sales, military exchanges and training programs have all been maintained or bolstered by the Chinese government.

Towards a Latin American international option

In the new geostrategic dispute between the great powers at the global level, Latin America should bet on a search for balance, greater pragmatism and a multilateral vision of the world, to privilege the option of cooperation over confrontation. As a bloc, the countries must avoid entrapments that put autonomy, principles and interests at risk. The bloc must also take firm positions when required and not fall into the perversity of “non-alignment.”

Latin America’s foreign policy must ensure the defense of peace and unrestricted respect for democracy, fundamental freedoms and international law. This has been a tradition in the region for several decades and must be preserved at all costs. Our community of democracies has not only its own life and identity, but also challenges to face and overcome.

Latin America is called upon to apply the principle of “Look at the whole, Look at the universe” (Respice Omnia) in order to be a player in a multidimensional and realistic manner in all global platforms, to ensure an intelligent international integration, a sustainable and inclusive development, and a growing participation in trade, investment and knowledge flows.

There must be a way of harmonizing different national positions to achieve common goals and face global challenges, such as poverty, inequality, climate change, energy and food security, and disarmament. This is essential in order to have a single voice and greater negotiating capacity in the world.

In short, the region still has the pending task of charting its own course, offering a bold leadership alternative for the Global South, while actively contributing to the construction of the new international architecture and agenda of this century. Latin America – in the words of the poet and Nobel Prize winner Octavio Paz – “deserves its dream.” This dream being a fertile land that inspires the ideals of democracy, peace and sustainable development.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.