The shadow of Russia hangs over the hornet’s nest of Sudan

Brussels and Washington state that the Wagner Group operates in the African country through shell companies and is involved in the exploitation and smuggling of gold

At around 9 p.m. last Wednesday night, the Russian company Concord, which is owned by magnate and Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin, posted a message on the social network VKontakte. In the missive, Prigozhin said he felt it was necessary “to inform everyone that there have been no employees of Wagner in Sudan for over two years. We have had no contact with either Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo or Abdel Fattah al-Burhan for a long time.” Generals Dagalo and al-Burhan, military strongmen who led the coup to overthrow the transitional government in October 2021, are now commanding the two opposing sides engaged in a power struggle in Sudan. Prigozhin, who is also known as Putin’s chef due to his close relationship with the Russian president and his catering services provided through Concord, added that none of his companies has “financial interests” in the African country.

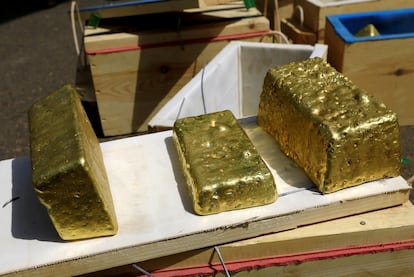

However, EU and U.S. sanctions against the Wagner Group ― a Russian mercenary organization spread across Africa, the Middle East, and the frontlines of the Ukraine war ― contradict Prigozhin. Brussels and Washington state that Wagner maintains a presence in Sudan through front companies by which, among other interests, it exploits the Sudanese gold-mining industry.

Prigozhin’s message was aimed at media outlets such as the BBC, The Washington Post and Jeune Afrique, who have raised questions about his relationship with Dagalo, the commander of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) who are battling al-Burhan’s Sudanese Armed Forces, as well as Wagner’s involvement in the gold industry, particularly through a company called Meroe Gold. The U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) added Meroe to its sanctions list in July 2020 over its links to Prigozhin, whom Washington accuses of exploiting the country’s natural resources and discrediting pro-democracy protests. Meroe Gold is a subsidiary of M-Invest, Wagner’s front company in Sudan.

On February 25 of this year, the Official Journal of the European Union published a list of those sanctioned for their links to the Wagner Group, which Brussels accuses of human rights abuses in Africa. Among the people and companies cited was Meroe Gold, which is based in Khartoum, and M-Invest, headquartered in Saint Petersburg, the heart of Prigozhin’s businesses. The sanctions report stated: “Meroe Gold is a cover entity for the Wagner Group’s operations in Sudan. It is closely linked to Yevgeny Prigozhin. By being affiliated with the Sudanese military, the Wagner Group secured the exploiting and exporting of Sudanese gold to Russia.”

Moscow and Khartoum have traditionally maintained close relations, before, during and after the military coup that deposed Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir in April 2019. But it was in 2017, at the height of the revival of Russian interest in the African continent ― with Wagner setting up shop in countries including Mali and the Central African Republic ― that the first concessions for gold mining were signed. This industry, which accounts for around 70% of Sudanese exports with around 90 tons extracted per year, experiences significant problems of illegal bullion trafficking, making it one of Sudan’s main attractions for foreign interests. Russia also has plans to build a naval base in Port Sudan, on the Red Sea coast, a point of great strategic value with the Suez Canal to the north and the Gulf of Aden to the south. Most foreign military bases in the region, including those maintained by the U.S., France and the United Kingdom, are located in Djibouti, south of the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait.

The dictator al-Bashir gave the go-ahead for the Russian military complex, but his fall and the arrival of a transitional government put the construction of the base in Port Sudan under review. Nevertheless, following the military coup in 2021, signals toward Moscow have been positive. On February 23, 2022, a day before Russia invaded Ukraine, General Dagalo arrived in Moscow to discuss cooperation and security issues. The second-in-command of the military junta headed by al-Burhan ― whom journalistic investigations have linked to the Wagner Group ― stated that if it did not threaten the security of his country, he did not see any reason to prevent Russia from setting up a military base on the Red Sea. A year later, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov shook hands in Khartoum with General al-Burhan. There was agreement on the base, but there has been no official confirmation from the now-bankrupt junta of its construction.

“Sudan is playing carrot and stick over the base,” says Roland Marchal, a veteran Sudan expert at the Paris-based Sciences Po Center for International Studies. “When [al-Burhan] met Lavrov he said yes, but they can’t be seen by the West to be maintaining that stance for fear that new sanctions will jeopardize the little they still receive.” Despite Wagner’s seemingly clear role in both training the Sudanese Armed Forces and the exploitation of the country’s gold, Marchal says that Russia’s influence in the country is still marginal, compared to that of other countries such as Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, and that Moscow’s relationship with Khartoum “does not affect” the current confrontation to any great extent. “Russia is pragmatic,” the analyst points out, “but its relations with the government will be more difficult from now on, whoever wins.”

EU sanctions and gold smuggling

In the EU sanctions report, Meroe Gold is linked to two local companies: Al-Sawlaj for Mining and Aswar Multi Activities. Through the former, Wagner operates in the gold mines to avoid any foreign sanctions; the latter is a Sudanese security company used for the supply of arms and the transport of Russian personnel inside the country on military aircraft. According to an investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, Aswar received $100,000 a month from the Wagner Group, which also covered its taxes and the salaries of all its employees.

While Prigozhin claims there have been no Wagner personnel on Sudanese territory for two years, the reality is contradictory. According to the specialized website Mining.com and local Sudanese media, at least 58 Al-Sawlaj employees have been investigated this year for smuggling between five and seven kilograms of gold out of the country. Of those employees, 36 are reportedly Russian nationals. The operation was carried out in Al-Sawlaj’s mines on the banks of the Nile. The investigation led to charges being brought against a Russian citizen, who was in charge of security at the mine. In July 2022, a CNN investigation in collaboration with the Dossier Center concluded that Sudanese gold was being smuggled out of the country via a Russian-led network. The report counted at least 16 Russian flights loaded with gold taking place over a period of 18 months. At the head of the operation was Alexander Sergeyevich Kuznetsov, a Wagner veteran who has been under EU sanctions since December 2021.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.