Secret recordings, million-dollar rewards and family betrayal: How the US hunted down El Chapo’s sons

The judicial crackdown against relatives, old partners and informants has been decisive in detaining top members of the Sinaloa Cartel. The evidence collected will be key to putting the capo’s heirs on trial

On Friday, April 14, the U.S. Justice Department announced charges against the Sinaloa Cartel’s global operations. Eight senior U.S. officials publicly disclosed the judicial offensive, including the attorney general for the Biden administration, as well as the directors of the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and the FBI. After Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán was sentenced to life in prison in 2019, U.S. authorities are now formally targeting the heirs of his criminal empire.

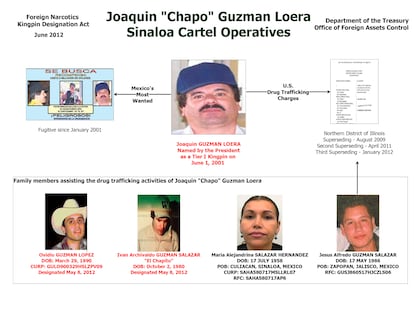

Four sons of the capo — Alfredo, Iván Archivaldo, Joaquín and Ovidio Guzmán — and 24 collaborators have been accused of an extensive battery of charges, such as organized crime, drug trafficking, illegal possession of weapons and money laundering. They are also named as the leaders of a global network involving murder, torture and transnational smuggling.

The three cases designed to deal a devastating blow against “Los Chapitos” were made public only in the last couple of weeks. However, court documents obtained by EL PAÍS suggest that the hunt dates back to 2008, targeting relatives, former partners and informants within the criminal network. The investigations that sank El Chapo are now more alive than ever — in fact, they’re the weapons being used by prosecutors against his successors.

“The indictment offers the most comprehensive look yet at the operations of the Sinaloa Cartel dating back 15 years,” reads the statement released by the Justice Department. The American government’s crusade against Los Chapitos includes at least five criminal cases filed before the courts of the Northern District of Illinois (in the Chicago metropolitan area), the Southern District of New York (Manhattan) and the District of Columbia.

More than 130 pages of court documents have come to light, detailing how cartel members fed their enemies to tigers, set up clandestine laboratories to traffic fentanyl, created a Pan-American drug trafficking corridor from Peru to the U.S. and wove alliances in Asia, using cryptocurrency payments that didn’t leave a trace. Meanwhile, DEA agents infiltrated the criminal group for a year-and-a-half.

The injection of new blood into the organization was intended to revolutionize the business. The founders of the cartel — Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada and El Chapo Guzmán — began the operation decades ago, trafficking in marijuana and cocaine. Since 2014, his children have been focusing on fentanyl, a drug that, less than a decade later, has plunged the U.S. into a public health crisis, causing tens of thousands of overdose deaths each year.

The vast majority of information remains classified. But there is one exception. The prosecution’s case in Illinois — decisive during the trial of El Chapo in New York — dates from 2009 and contains more than 950 documents in its file, such as arrest warrants, plea agreements, and negotiations to facilitate confessions and accusations. Prosecutors first targeted the top rungs of the Sinaloa Cartel, launching themselves against Guzmán and El Mayo Zambada, who remains a fugitive with a $15 million reward hanging over his head.

Long before going against the heirs of El Chapo, the U.S. Justice Department went after Jesús Vicente Zambada Vicentillo, El Mayo’s eldest son. He was arrested in Mexico City in March 2009 and extradited almost a year later to the United States, which identified him as responsible for trafficking $1 billion in marijuana and cocaine into the country. Behind bars, the authorities forced him to make the most difficult decision of his life: they offered him a deal to rat on his father and his former associates, in exchange for a reduced sentence. He accepted.

“I began to realize how everything was done,” said El Mayo’s son, recalling how he got started in the business, meeting with other drug lords and corrupt police officers. “Little by little, I began to get involved,” he added, when he testified during El Chapo’s trial in 2018. By then, he was about to complete almost a decade collaborating with the authorities, although his lawyers hinted that he was already working with the DEA long before his arrest.

Vicentillo told the Justice Department how assassinations were ordered in the cartel, how the profits were distributed, how El Chapo escaped from prison and how he met with top-level Mexican politicians. The scandal made headlines in the international media. “At El Chapo’s Trial, a Son Betrays His Father, and the Cartel,” read a headline in The New York Times.

“By providing the jury with a unique look from inside the cartel, he not only exposed the leadership of El Chapo Guzmán, but also that of his own father, which seems unique to me,” said Amanda Liskam, who was part of the prosecution during the trial. Liskam said that the kingpin’s cooperation was “comprehensive,” adding that he also spoke about how other relatives of the leaders were involved. Vicentillo Zambada ultimately received 15 years in prison, although it was discovered that he was already free by April 2021. “I made bad decisions, which I accepted and continue to accept responsibility for,” Zambada stated during his trial.

“You are one of the highest people they have ever sent me since I’ve been on the bench,” said Rubén Castillo, district judge for the Northern District of Illinois. “If there is a so-called drug war — we have lost it,” he said. “It is time for this country to do something different.”

During the administration of former president Donald Trump, the judge struck down arguments proposing the construction of a U.S.-Mexico border wall as a solution to drug trafficking. He also criticized those who called the son of El Mayo a “traitor” or a “rat.”

“You cooperated with the United States of America. That is what happened. And if we didn’t have cooperators, the Department of Justice simply would not win cases. Perhaps we have lost the war on drugs, but we cannot afford ourselves the luxury of losing the war on crime,” said Castillo. After sitting down with authorities dozens of times, Zambada vowed to continue cooperating with authorities, even after he was sentenced.

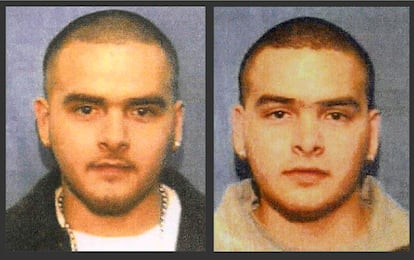

Before Vicentillo Zambada, Pedro and Margarito Flores were top collaborators: twin brothers who took their experience working at a McDonald’s to expand the presence of the Sinaloa Cartel in the United States. They began betraying their partners in October 2008, also through the Illinois court. The Flores brothers recorded around 70 telephone conversations with members of the cartel, including one between El Chapo and his son — Alfredo Guzmán Alfredillo — coordinating the delivery of a shipment of 20 kilos of cocaine to Chicago. In the recording, they discussed the logistics for the shipment and payment of the merchandise.

There are almost a dozen recordings by the Flores brothers, dating from the end of 2008. Many times, these were done by placing a hidden microphone in the waistband of their pants. “Yesterday’s [deal] went very well,” Pedro Flores tells Alfredo Guzmán in one of the calls, regarding a shipment of 20 kilos of cocaine. “I was telling your old man [El Chapo] to see if there’s an opportunity for them to send us another five. I don’t know if you have them. I’m going to deposit the check for [the 20 kilos] tomorrow. See if you have another five and let me know,” the twin is heard saying.

Call descriptions are straight to the point: “Alfredillo asks why the heroin hasn’t been picked up.” “Pedro asks Alfredillo for a clean phone number to contact El Chapo.” “Pedro tells Alfredillo that he has just spoken with El Chapo and has already arranged the payment.”

The cooperation of the Flores brothers resulted in almost 20 drug busts, dozens of arrests in Mexico and the United States, as well as the extradition of several drug lords, including Vicentillo Zambada. The brothers were sentenced to 14 years in 2015 by Judge Castillo. The twins would later return to testify against El Chapo in Brooklyn.

In 2014, Jesús Raúl Beltrán — the brother-in-law of Alfredo Guzmán and one of the defendants in the Illinois case — was captured while he slept at his home in Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa. In 2017, his lawyers filed a motion claiming that their client was the victim of torture at the hands of the Mexican Navy, with the consent of U.S. agents. The marine unit allegedly entered while brandishing heavy weapons. They isolated him from his wife and daughter, handcuffed him, and began beating him and suffocating him with a plastic bag in his kitchen, according to Beltrán’s testimony.

In his affidavit, Beltrán said the group threatened, “Now, you son of a bitch, are you going to cooperate or do you think that your daughter can withstand a plastic bag?” He said that the men also threatened to gang-rape his wife and kill his family. “We are going to kill your mother with a shot to the head or maybe we’ll just hang her from a bridge,” they told him, according to the affidavit.

“My captors commanded that I was going to tell them where Ivan Archivaldo and Alfredo Guzman Salazar lived, and I was going to take them there, or they would immediately massacre my family,” the statment continued. Beltrán, however, maintained that he did not know where El Chapo’s children were.

Beltrán also claimed that, after being transferred and humiliated in a military camp, some officials offered him political asylum in exchange for revealing the whereabouts of the Guzmán brothers. He told them that they were friends from elementary school, but that since then, he hadn’t heard from them. Later, Beltrán commented that he met with the brothers in restaurants and nightclubs — meaning, he didn’t know where they lived. Later, they asked him what cars they drove and where they ate.

Alfredillo’s Guzmán brother-in-law claimed that — in addition to being suffocated — he was electrocuted, tortured with heavy metal music, doused in ice water and forced to confess in front of DEA agents.

“This recitation included admissions that I, Ivan Archivaldo Guzman Salazar, and Alfredo Guzman flew from Culiacán to Chiapas to buy cocaine. I further admitted that each man was tasked with a particular job – I loaded the cocaine into the plane, Alfredo stacked the cocaine inside the plane, and Ivan piloted the plane,” Beltrán said in his affidavit.

Beltrán’s complaints were ultimately dismissed. In September 2019, he was sentenced to 28 years in prison for trafficking marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine and heroin, after refusing to cooperate with the authorities and maintaining that he was tortured during his detention.

The Chicago court didn’t stop its pace even after the fall of El Chapo and the retirement of Judge Castillo that same year. In December 2021, Guadalupe Fernández Valencia — known as “La Patrona” — who was most powerful woman within the Sinaloa Cartel, was sentenced to 10 years in prison. This was a reduced penalty — the 60-year-old woman signed an agreement with the authorities to collaborate. And, in January of this year, Felipe Cabrera Sarabia — alias “El Rey de la Heroína” (“the king of heroin”) — pleaded guilty to drug trafficking. He faces a sentence of 10 years to life in prison.

The Illinois indictment — the same one in which 22 people were charged, from El Chapo to El Rey de la Heroína — includes eight criminal charges against Joaquín, Iván Archivaldo and Alfredo Guzmán. It also mentions Ovidio Guzmán — captured in Culiacán this past January and currently in the process of extradition from Mexico to the United States — who is charged separately. There are four charges for drug trafficking, two for organized crime, one for money laundering and another for carrying illegal weapons. The penalties range from 10 years in prison to life imprisonment; the fines, from $500,000 to $10 million.

“The Chapitos allegedly assumed their father’s former role as leaders of the Sinaloa Cartel,” reads the DOJ document, which accuses El Chapo’s sons of coordinating the criminal group’s operations, amassing the profits and laundering them. The heirs are said to have accelerated the trafficking of drugs and chemicals needed to manufacture fentanyl, trafficking it via planes, submarines, boats, shipping containers, tractors, buses, cars, trains and tunnels to cross the U.S.-Mexico border. The network involves 10 countries in the Americas: the United States, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Peru.

“The charges stem from a decades-long, multi-district investigation,” the statement reads. The U.S. government is currently offering a reward of $10 million for the capture of Alfredo and Iván Archivaldo Guzmán Salazar and $5 million for Joaquín Guzmán López.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.