An inside look at Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel

Since 2018, Eduardo Giralt Brun has been trying to understand the psyche of the foot soldiers in the criminal group. His work has led to two documentaries and a book of photography that challenge the glamorous TV depictions of narco culture

The day that “La Vagancia” understood that he could die in a shootout on any given day, he decided to leave a record of his time on Earth. For youths like him, hitmen and pawns of the drug world, death comes early and without warning: on any street corner, during any brawl, settling of scores or from a stray bullet. And even though he dreamed of quitting the Sinaloa cartel and finding a regular job, he also knew that the most likely way of leaving a criminal group is either as a prisoner or as a corpse.

That is why he decided to fill a memory card with all the photographs and videos he had made during his time with the cartel and placed it in the care of one of the few people he knew who were not part of that life, someone who might be able to do something useful with it: Eduardo Giralt Brun.

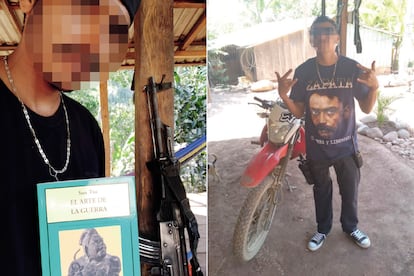

And Giralt Brun, a 34-year-old filmmaker from Venezuela, transformed these files into the book Sicario Warfare, released this year by the independent publisher 550BC, and into the documentary Sinaloa Foot Soldier: Inside a Mexican Narco-Militia —with Emmanuel Massú and Pouria Khojastehpay—, an inside look at daily life for the militiamen led by La Vagancia. The footage shows them on trips across the mountain and in confrontations with rival gangs; it documents moments of boredom, their weapons, their camaraderie.

La Vagancia, whose real name is not revealed, is 31 years old. He joined the Sinaloa cartel at age 22 and met Giralt Brun in 2018. The latter was working at the time for a movie director who wanted to shoot a film about life in the Sinaloa underworld, something like Mexico’s answer to Fernando Meirelles’ 2002 City of God. Giralt Brun was hiring youths in northern Mexico to work as actors and extras, kids from rural communities and poor neighborhoods. And many of the youths that he met were working for organized crime. To his surprise, a considerable number of them wanted to be in the movie, contrary to what he had been expecting.

Giralt Brun was always interested in understanding the psychology behind that small percentage of the population that lives a life of crime. He also wanted to understand the mindset and worldview of youths from poor backgrounds without many options for advancement in life. So he decided to shoot a documentary about them with his cellphone and help from his friend and work colleague Emmanuel Massú, a well-known rapper in Sinaloa who sometimes worked as a fixer for reporters as he was able to move easily within that shady world.

“I focused on the gatilleros, the foot soldiers. The stigmatized young men who also suffer from that hegemonic masculinity. And 90% told me they didn’t want to participate. But then we found La Vagancia, who is a great character,” says Giralt Brun on a recent sunny February day inside his two-bedroom apartment in Mexico City. The living room is decorated with relics he collected during his fieldwork, such as a stick with the drawing of an AK-47 assault rifle used by the Sinaloa cartel to punish its unruly members.

‘The Plebes’

Giralt Brun is a tall, stocky man with tattoos on his arms, a shaved head and a thick mustache that is the outstanding feature on his face. He wears tight clothes and there are three medals hanging from his neck. He speaks with his entire body, energetically. Each word is reinforced with gestures and shoulder movements. And when the conversation gets interesting, he bites his lip as a half-smile plays across his lips.

The documentary that he made with Massú, Los Plebes, premiered in 2021 at independent film festivals and did not have much commercial success. Audiences accustomed to the glamorous, adrenaline-driven vision of the narco world depicted by Netflix were unimpressed by his vision, which comes closer to the “dirty realism” of 20th-century Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini. There are hardly any shootouts or action scenes. There are no big mansions, luxury cars or narcocorrido ballads. What there is a lot of is grey-looking suburbs, unfinished brick houses, concrete floors and cheap clothes.

The film follows the day-to-day life of La Vagancia: he plays videogames, drives across town, takes care of his dog, attempts to pick up some girls, and is always looking at his phone, because his boss could call any time about a job that needs to be done. In fact, even the lead character told them that they had made a very boring movie.

The moviemakers have also been strongly criticized for “humanizing” these foot soldiers and justifying their violence. But Giralt Brun and Massú are tired of the polarity of the concepts of good and evil, of executioner and victim. “Is a 15-year-old boy who gets recruited by the narcos not a victim?” asks Giralt Brun. “If this were to happen in Africa, we would call them child soldiers. But over here we see them as the scum of the earth. You cannot build a country if these kids are not even considered citizens.”

From cartel to paramilitary group

The documentary Los Plebes was filmed in 2018, and as the years passed La Vagancia rose up the cartel’s chain of command. From a foot soldier, he went on to lead his own combat unit and train new recruits. It was at this time that La Vagancia sent Giralt Brun and Massú a memory card with photos and videos. The change in La Vagancia, as well as the criminal group itself, can be seen in Sicario Warfare and Sinaloa Foot Soldier. “There is an evolution of a cartel into a paramilitary group that wants power and territory, and is no longer just trafficking drugs,” says Giralt Brun.

In the prologue to Sicario Warfare, the co-author of the book, Pouria Khojastehpay, reflects on how the idea of anonymity and secrecy in organized crime has changed today: “The mafia is not this secret world that you think is impossible to enter. The industry has evolved and the current generation of gangsters is increasingly less against being written about or having their photos shared. Many bosses and their men like to talk, boast and enjoy being portrayed by authors and directors as real, modern-day versions of Tony Montana [from the 1983 film Scarface] or Michael Corleone [from the 1972 The Godfather].” Giralt Brun adds: “They are fed up with so many stories told by others, they want to recover their own story.” In other words, they want to take control of the discourse.

During the short documentary, La Vagancia reflects on his life as a hitman: dying is easy, escaping is hard. He explains: “One thinks about a lot of things in a few seconds when there is a clash. The adrenaline can feel good or sometimes bad, it all depends on the mood. But over time, you start to feel afraid. It’s difficult to explain. Sometimes you think about leaving this job. Too many times. I do feel, my feelings have not disappeared, nor do I have a heart of stone. What I am living is normal, it’s work. I don’t consider myself a bad person.”

On these reflections, Giralt Brun says: “It’s very abstract to think of yourself as a character. And this kid is doing it. He’s aware that his life has a dramatic side.”

Giralt Brun, who studied visual art, doesn’t like to be considered an expert. He refuses to use academic terms and focuses on what he has learned from the fieldwork. He makes constant references to books and classic films. As the interview goes on, he brings out more and more books and notebooks to illustrate his points, such as The Corner, a portrait of the low-income inner-city neighborhood of Baltimore, written by Ed Burns and David Simon, the creator of the acclaimed series The Wire.

“It’s a classist argument that these kids get involved with narco groups because they are poor. Most of the poor kids from these neighborhoods are looking for honest work,” he says. “And crime isn’t easy. You earn as much as you would at [convenience store chain] Oxxo. What’s interesting then, is why do they do it?”

He adds: “There are poorer countries that don’t have the violence of Mexico. It’s a perfect storm, there is not just one reason. It’s the ban on drugs, the lack of welfare, having the Americans as neighbors…”

Fear and morality

Spending so much time surrounded by people who murder and make others disappear as part of their job is not easy. “I have been afraid, especially when drugs and alcohol are involved,” says Giralt Brun. When he was with the cartel members, he was nervous about getting shot in the back of the head while going to the bathroom. He compares the experience to swimming in the open sea, something he loves: you have to accept that you are in the middle of nature and have no control. Anything could happen.

But Giralt Brun was not just affected by fear. Being exposed to such high levels of violence and extreme experiences also affected his way of understanding and assessing this reality. “I’m not a human rights activist nor working with the authorities, I’m a chronicler. But the moral compass starts to shake, it’s difficult.”

“All of them are going to tell you that they only kill their enemies, not innocent people. They have a narrative of good versus bad: they [the enemies] are the bad guys and we are good guys. I have not met anyone who told me ‘I’m a bastard and I like to kill innocent people.’ In their view, theirs is a fair fight,” explains Giralt Brun, who says that you end up telling yourself ‘small lies’ to cope with it. Like telling yourself that the killer that you have become close to after hours of interviews is “the least bad of the bad,” says the filmmaker. That the world is a very ugly place anyway, and that’s just life.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.