Katherine Corcoran: ‘Contempt for the press is dangerous. In that, López Obrador is like Trump’

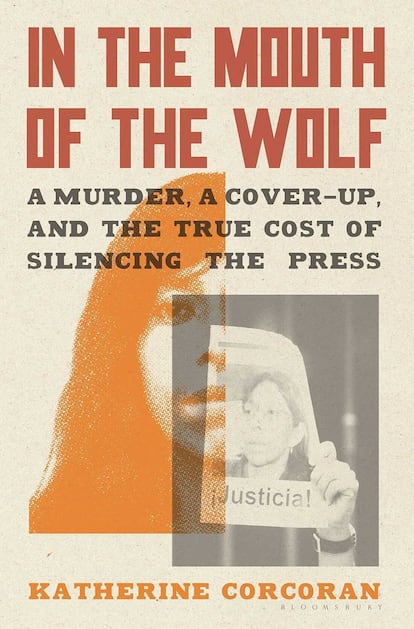

Former AP Mexico bureau chief publishes ‘In the Mouth of the Wolf,’ an investigation into the 2012 murder of reporter Regina Martínez that carries a bigger message about what happens in a society when the press is silenced

The journalist Katherine Corcoran stopped in front of Isabel Núñez’s house in Xalapa, the capital of the Gulf state of Veracruz, and rang the doorbell. She believed that eight years were enough for the woman to be willing to talk about the murder of her neighbor, the reporter Regina Martínez. “I was wrong,” Corcoran writes in In the Mouth of the Wolf, a book detailing the investigation she did into the Martínez slaying. Like others, the neighbor did not want to talk to Corcoran. “We don’t talk about that, that chapter is closed,” she yelled at her from the first-floor window. Corcoran, however, traveled to Veracruz dozens of times and managed to conduct hundreds of interviews between 2015 and 2022. The result is an exhaustively reported tale that offers new clues about the crime and is also a warning about something bigger.

“I wanted to explain what happens in a society when the press is silenced,” Corcoran, 64, told EL PAÍS on a recent Thursday morning on the terrace of her hotel in Mexico City. The day before, she had presented the book — only available in English for now — in the Mexican capital. On one side of the table was a black-and-white photograph of Martínez with a serious expression on her face, aviator glasses and a notebook in one hand. Corcoran was the Associated Press (AP) bureau chief for Mexico and Central America when Martínez, a reporter for the weekly investigative magazine Proceso, was found dead inside her home in 2012. That year, six other journalists were killed in the country, according to the organization Article 19; a decade later, in 2022, there were 12.

Martínez had dedicated her career to investigating corruption and she was one of the most respected and uncomfortable reporters in all of Mexico. The official version of events held that the journalist, who was then 48, had been murdered by two men that she knew personally. It was claimed that she was in a relationship with one of them. One of the alleged criminals was sentenced to 38 years behind bars and sent to prison; the other is still missing. Colleagues and friends of Martínez, however, always viewed this theory as improbable and absurd. The judicial investigation, moreover, had been full of irregularities.

“They were just scapegoats,” says Corcoran. She began to follow different lines of investigation and often found herself in dead ends. Finally, after reviewing each of the hypotheses, she found herself back at the beginning: an article published by Proceso three weeks before the murder. The byline of the story did not show her name, but instead that of her colleague Jenaro Villamil. But Martínez had been with him in Veracruz. The article targeted two high-ranking state officials with ties to organized crime: Reynaldo Escobar, who had been a state prosecutor, and Alejandro Montano, former secretary of Public Security.

Question. You believe that Regina Martínez was murdered because of an investigation she was working on and you go back to the Proceso article that was published a few weeks earlier. Do you think authorities should continue investigating along these lines?

Answer. Yes. We really don’t know who is behind this murder. Since there was such a strong cover-up in this case, journalists are scratching, scratching, scratching information. Presenting the data that I discovered is all I can do with this kind of cover-up and considering the fear there is to speak out about this case.

Q. Did you know from the beginning that it would be difficult to find out who murdered her?

A. As a journalist I wanted to find out, but I didn’t manage it. Someone suggested that I take the book to the prosecutor to see if there is anything useful for the investigation in there. I’ll do that.

Q. What is the question you have asked yourself most frequently since the investigation began?

A. Obviously, who was behind this. I don’t think we now have the actual perpetrators either. They were just scapegoats. It was a purely made-up story. The guy in jail had nothing to do with it, he’s not guilty. The question is who was behind this crime. It is obvious to me, given the cover-up and the fear, that it was someone in power. We don’t know who.

Q. You spoke to Regina Martínez once. What do you remember about that conversation?

A. I was the AP bureau chief. There was a breaking news story and I was looking for someone to cover it. It was unprecedented, the drug traffickers had dumped bodies on a highway in the middle of the day. At that time we did not have a correspondent in Veracruz and so, while a correspondent from Mexico City went over there, I was looking for someone to write up a story for us. I called Regina and asked if she could help us. She told me that she was very busy on an article for Proceso. I didn’t think about this call until six months later, when I read that she had been murdered. “Her?” I thought. There was a narrative that murdered journalists were always narco-journalists, but she was a different type of journalist.

Q. What was she like?

A. She was a journalist ahead of her time. From the beginning, she wanted to be an independent reporter. That was a bit strange at that time, in the 80s, because the press was highly controlled by the party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). From the beginning she was cut off from other members of her trade and from the beginning she was a problem because she didn’t play the game. She suffered a lot of harassment, but it didn’t turn fatal until late in her career. I spoke to her closest friends and they say that she was their beacon. She was very rigorous and taught her way of reporting to younger journalists. She was dedicated. Because of that, and because of the harassment she experienced, she was very hermetic about her personal life. That was her way of protecting herself.

Q. Why were you interested in investigating her murder?

A. I was quite shocked, upon arrival in Mexico, by the number of murders and the lack of reaction. The government insisted that they were corrupt journalists, that they must have fallen into “bad ways,” and there were no real investigations. My job was to explain Mexico to the rest of the world, and I had no explanation for what was happening. When Regina was killed, it was a watershed. I knew, and everyone else knew, that she was not a corrupt journalist. There has been no justice. A lot of my colleagues keep pushing because we want justice for her.

Q. What has been the biggest challenge of doing research in Mexico?

A. Protecting sources because it was so dangerous for them to talk to me. I had to protect their identity and so I couldn’t tell other people who I was talking to. As a journalist, we always want to run information by other people, but I couldn’t give names to anyone.

Q. Why is Regina Martínez’s story of interest in the United States?

A. My book has, for me, a bigger message about the press and freedom of expression. I wanted to tell Regina’s story to the rest of the world and explain what happens in a society when the press is silenced. In Mexico, for decades, most of the press was controlled by the party. Now Mexico is coming out of this and trying to create a truly independent press. There is still corruption and a lot of mistrust among journalists, but from my point of view, independent and investigative journalism in Mexico has improved a lot in the last 10 to 15 years.

In the United States it is already the other way around. It’s like Mexico before, with the PRI. In the United States, the independent press has always been valued because it is fundamental to maintaining democracy, but now this idea is being dismantled. Today, if someone contradicts the government, they are branded corrupt or a liar. We are experiencing a campaign of contempt for the press. My purpose was to teach readers in the United States what happens if we continue down this path, if nobody trusts anything anymore, if nobody believes any data. This system is a system of criminal governments, like those of Veracruz. We are still far from this point, but I wanted to show where this road ends.

Q. The president of Mexico dedicates a space in his morning conferences to expose critical journalists.

A. [Andrés Manuel] López Obrador resembles [Donald] Trump in several ways. But in this sense, he is similar because he believes that journalists should be on the side of the president and support him. If not, they are the opposition, they are the enemy. That was the system under the PRI. But it is a new concept in the United States. Contempt for the press is dangerous. In that, López Obrador is like Trump. The environment for journalists in Mexico has gotten worse due to their attacks, but the journalism that is done is increasingly professional, rigorous and investigative.

Q. You have spent 10 years investigating the murder of Regina Martínez. The number of murdered journalists has grown. Have you gotten any answers as to why democracy in Mexico has become so dangerous for the media? It is a question that is posed in your book.

A. Professor Guillermo Trejo and his team study violence in emerging democracies. Earlier, in Mexico, there was a very strong control system from the presidency, even over the mafias and the cartels. With democracy, the president lost this central control. The cartels had to make new deals with local politicians. Sometimes the politicians joined the mafias, as in Veracruz, and it was no longer possible to distinguish who is who: who is the government and who is the cartel. Trejo calls it the gray zone. When journalists touch this gray area, it is dangerous. Almost no one in Mexico investigates drug traffickers because everyone knows that it is very dangerous, but they do investigate public corruption a lot. That’s what Regina was investigating. Her entire career she investigated corrupt politicians, but in the last years of her life that lead often led to drug traffickers.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.