Warren Ellis: ‘Nick Cave told me he got me in the band because I was fun to take drugs with’

After a stellar career with his group Dirty Three and Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, the Australian musician is presenting ‘Ellis Park,’ a documentary about an animal sanctuary in Sumatra

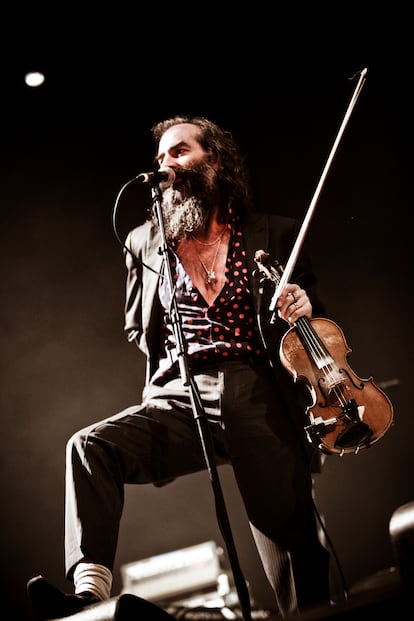

It’s not easy to define Warren Ellis. He’s a musician, about that there is no doubt. He has been ever since his father bought him a violin in Ballarat, the small Australian city in which Ellis was born 60 years ago. He is of the breed of musicians who are uninterested in taking that step forward into stardom. But rock fans have known of his work since the early 1990s, when he founded Dirty Three, an intense instrumental Melbourne rock trio of intermittent periods of activity. In 2024, they released Love Changes Everything, their first studio album in 12 years. It should be noted that in Australia’s second most-populous city, a unique sound has been created that has its roots in punk. It is loud, ramshackle, cacophonous, dark and fascinating, as allergic to convention as the Devil himself. Should a chorus appear, its proponents would run in the opposite direction. It is music made by misfits who seem to live in a constant existential crisis.

Over four decades, this scene has produced dozens of bands, but one name stands out above all others, one almost universally known nowadays: Nick Cave. “Now, everybody knows how charismatic he is. But in a certain circle in Australia, Nick was this big shadow that just kind of hovered over everything, hovered over the music thing, hovered over the creative. And in 1980, when his group at the time, The Birthday Party, went to London, they just grew in stature. Jim White from Dirty Three swears they came back and they were all 30 centimeters taller. When I met Nick, I was living with a heroin dealer in Melbourne in the mid-eighties who used to deal to all the rock and roll people, Nico would come around, and Johnny Thunders. Nico came and stayed in the house for two weeks. And Nick turned up, he had this kind of mystique around him. He sat in a chair and then, when he left, nobody was allowed to sit in the chair. That was Nick’s chair. It was amazing, he had that sort of aura,” Ellis recalls.

In the mid-1990s, Ellis began to collaborate with Cave. What began as a side quest turned into his main gig when he became a permanent part of The Bad Seeds, Cave’s band. Little by little, Ellis’s role took on weight until, finally, he was Cave’s right hand man. Today it seems that Ellis is Cave’s shadow, as though it is absurd to speak of one without the other. On December 5, they will release their new album Live God, comprised of live performances from the group’s last studio release, Wild God. “I’ve played with Nick for 30 years now, and I’ve been watching him from the side or the back. But I had to mix the live concert for this, so I had to watch the video. For the first time since the early nineties, I saw him from the front, and I was moved to tears. I suddenly got the emotional thing that I got from watching him perform, which is very different to when you’re in there as part of the machine. He’s an amazing performer, Nick. Still,” he says.

Although Ellis roundly denies it, Cave’s albums would sound different if he weren’t part of the equation. He’s a bit like the frontman’s musical director. Cave acknowledges that, thanks to Ellis, he sounds more atmospheric and less guitar-driven. “Don’t make such a big deal out of me. Nick isn’t afraid of anything. If I weren’t here, he would have done something else. I’m the lucky one. I’m good at collaborating. Working with others, whether it’s Nick or Dirty Three, brings out the best in me,” he says. “When we were on tour, we had this discussion. It was something about performing a song and he didn’t want to do it. And I’m like, ‘Well, I want to, and this is my reason, and that’s the end of the story.’ And he goes, ‘OK.’ And I got excited, ‘Look, that’s why you got me in the band. It’s because you know that I don’t want to take an easy road and I’ll always fight to the end for this stuff.’ And he goes, ‘No, I got you in because you were fun to take drugs with,’” Ellis recounts, ending the story with a guffaw.

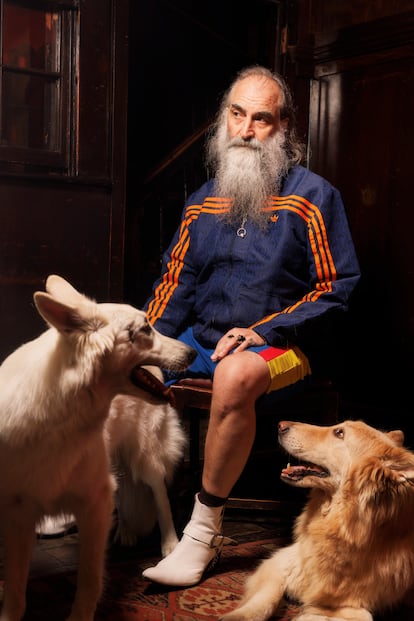

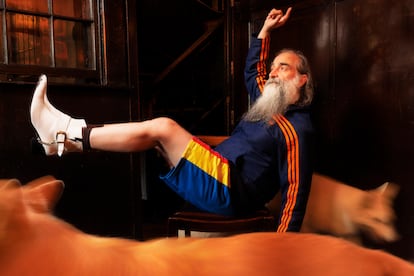

It’s a sunny Friday in July and Ellis is on vacation. The U.S. leg of the Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds tour ended in May and now he has a few months to focus on his own projects. He arrives, punctual as clockwork, to the interview at The Flask Tavern, a historic pub in Highgate, an area in north London known for its cemetery, in which everyone is buried from Karl Marx to George Michael. His appearance makes it clear that, in addition to being a musician, he is a character. A Lidl short tracksuit, 1980s sunglasses, baseball hat and white boots with a Cuban heel. “You like them? I bought them here in London, but they’re made in Spain,” he says proudly. If all this — his white hair, the chest-length beard — didn’t make a big enough impression, he is accompanied by two spectacular dogs, white Swiss shepherds, a female with snow-white fur and a copper-hued male. They never leave his side. “Especially her,” says Ellis. “Hers is unconditional love. Even when I do therapy on Zoom, she sits next to me. Two years ago, I had a breakdown. A big one. And her unconditional love helped me come back,” he explains, stroking the pup.

He passes the afternoon on the pub’s charming patio alongside an ample selection of neighbors. They’re the kind of beautiful people who seem well-educated, well-off and content. A Social Democrat utopia, a stone’s throw from Camden Town. “I live close by now, in my girlfriend’s house,” he says. Ellis is dating the legendary U.S. model Kristen McMenamy. “How long have we been together? Officially or extra-officially? Extra-officially, three years. Officially, I’m not sure,” he says.

Until recently, Ellis lived in Paris with the French musician Delphine Ciampi, his wife since 1999, and their two children. Did their breakup have anything to do with the breakdown he mentioned? “My professional life was always really good, but my life outside of that … I had kids and family and stuff, but I never really knew how to fit into that aspect of life, so I was just always working and pushing all the problems behind. And one day I had to face this tsunami of shit and bullshit and lies. Two years ago, I saw a psychiatrist and got diagnosed — he said I was suicidal, I was anxious. I was out of control. He was like, you need to take antidepressants,” Ellis explains. He speaks haltingly, but his sincerity is overwhelming.

“I haven’t had a drink in 25 years,” he tells the waiter, who had offered him a pint. Instead, he orders a club soda with lemon. Ellis, like Cave, lived with addiction for two decades — to heroin, to alcohol, to whatever was around. They were two wild men, until they weren’t. “My epiphany, if you want to call it that, happened when I watched a lot of people die. My really dear friend Dave McCone who was in the Triforce, he was the singer in that band. I’d just been talking to him, and at that stage, I was just paralytic drunk on a couch at my younger brother’s house. He died, he overdosed, and I couldn’t go to his funeral. Then a bass player in another band I was in had a baby, went home, had a thing and OD’d. I was pouring the thing in and my brother came in and he punched me and he just said, ‘You fucking asshole, Andrew died a week ago and look at you.’ At that stage I had just met my girlfriend, who became my wife. I was on this couch, waking up, drinking half a bottle of whiskey, blacking out, waking up, drinking the other half, blacking out, going down the pub, drinking, blacking out, pissing myself — I was a mess. My brother said to me, ‘What’s your fucking problem?’ I said, ‘I don’t know.’ I got on the plane and decided if I arrived in Paris alive, I’d stop. I had just had heroin, alcohol. I somehow got home and I woke up and that was it. I stopped, just like that. I put myself in bed for six weeks. The alcohol was hard to detox off. It was probably dangerous to do that unsupervised, because of the amount and the frequency that I was doing. But I didn’t pick it up again. Then I had children and I made a promise to myself that I would never let them see me how I was, to see me drunk or on drugs.”

That was 1999, when Ellis was 35 years old. Months later, Cave got one of his biggest inspirations, the legendary pianist, composer, activist and true rebel Nina Simone, to perform at a festival he was curating in London. Simone was 67 years old and in terrible health. It was the penultimate time she would play for an audience. “Nina Simone’s concert was… indescribable,” says Ellis. “She was a godlike figure for us, you know, but everything seemed to be against her. When she came out, she could barely walk. It seemed impossible that she would be able to play. And she simply did it. You could see how the music possessed her and filled her with an energy she didn’t have. I was so impressed,” he says. The story goes that when Simone left the theater, as the audience was still in shock over what they had witnessed, Ellis went up to the stage as if possessed himself, collected a piece of chewing gum that she had stuck to the bottom of the piano before she began to play, wrapped it carefully in the towel Simone had used to wipe off her sweat, and saved it in a plastic bag. “I have no idea why I did it,” says Ellis. “It was an impulse to save something that seemed unique to me and that was going to be lost. But when I got home, I didn’t know what to do with it. With time, it became a totem, I felt like it protected me. But it was a private superstition. I never thought that anyone would be interested in it.”

He couldn’t have been more wrong. In 2019, exactly 20 years later, Denmark’s national library was preparing The Nick Cave Exhibition: Stranger Than Kindness. The idea was to fill eight large installations with hundreds of objects that formed a vision of Cave’s creative journey and universe. The singer wrote to Ellis to see if he had anything that he’d like to include. “I have Nina Simone’s gum,” Ellis replied. “I want it!” said Cave. “From there, it evolved. Somehow, the gum grew in importance. Suddenly, the whole world acted as though it was sacred. It wound up being exhibited in an urn and it became one of the centerpieces of the exhibition,” Ellis remembers.

That process by which an once-insignificant object became a priceless relic is told in Ellis’s autobiography Nina Simone’s Gum: A Memoir of Things Lost and Found, which has sold 100,000 copies and been translated into 10 languages. “Right now, the gum is at my house. It’s hard to know how much it’s worth. Any object that is shown in public has to be insured. The first time, it was for $1,000, then $100,000, and it keeps going up. Especially after the publication of the book. If it went to auction it could be madness. It has taken on weight, it’s the memory of a night that has now reached mythical dimensions,” he says.

Perhaps one of the keys to all this is that he never wanted to profit from the gum. He wears a white gold reproduction of it on a necklace. If he had made hundreds of copies, he could have easily sold them. But he didn’t. He preferred to commission a handful of silver replicas that he has been giving away to friends and family. “It never occurred to me to market it. It’s as simple as that. I’ll tell you something: I also keep a cigarette butt from Marianne Faithfull. If I combined the DNA on the two, I could create a super-woman.”

The gum has taken him down strange paths. For example, it’s there at the origin of one of his most recent projects, Ellis Park (2024), a documentary directed by Justin Kurzel. But to get to that point, it’s necessary to take a step back, to the pandemic, when Ellis first heard Femke den Haas, an activist who has dedicated herself to rescuing animals who have fallen victim to trafficking in Sumatra. “I’d been looking at doing something. Music and all that has been so kind to me all my life, I was in a position where I was earning money, and I wanted to do something but I didn’t know how or where to put it. And then a friend of mine said, ‘I know this woman. I’ll introduce you to her.’ And I met Femke on a Zoom chat. And I knew straight away, this woman was real.”

Den Haas had earned a reputation, and she was being called in every time the Sumatran police found a trafficked animal. But she had nowhere to care for the creatures, many of whom were dying or could never return to live in the wild. “And that’s how we opened an animal sanctuary in Sumatra, where I had never been. It was all done over WhatsApp and social media. I threw it out there, and all the fans, they all mucked in, and we raised $115,754, and built the infrastructure, the park, the school, the veterinary hospital, the enclosures, because they’re all animals who can’t be released into nature,” Ellis says.

This was the story Ellis told Justin Kurzel, and the filmmaker proposed making his first trip to the park into a documentary. This is where the gum re-enters the narrative. “I sourced how to get a sort of three-meter version of the gum made in pink marble in Italy,” says Ellis. “I was going to put it on a boat, take it up the river, and put it on top of a hill.”

Didn’t that plan sound a bit like the film Fitzcarraldo?

“We actually realized that it was a rather grotesque idea. It was actually Nick Cave who said to me, ‘Well, this is just my opinion, but your book is so beautiful, because it’s this tiny little insignificant thing. And just have a think about whether making it that big isn’t rather grotesque?’ And I started thinking about that, and I thought, he’s got a point, it’s kind of obscene.”

The documentary became instead a journey from his origins to the park, an intimate trip in which Ellis confronts many of his demons. “I wanted it to be a film that was only about the park. I didn’t feel the need to talk about my life, I’m very private about my life outside of music. I don’t awaken curiosity in the press. I don’t write lyrics, I make music, people like it or they don’t. If you like it, great, and if you don’t, it’s all the same. It doesn’t bother me. But Justin said to me, ‘Look, we have to assume that most of the people watching this aren’t going to know anything about you, so you have to give them a bit of a backstory.’ He said, ‘I want to go back home, to Ballarat, I think the answer is there.’ And for me, that presented problems. My dad had cancer, my mum had dementia. While we were doing the filming, it was incredibly intimate and very, very delicate. At the end of that week of shooting, my mum went into a home and she’s still there now. My dad went in, had an operation, and I stayed on after the tour and took care of him for a month. He died at the end of that year.”

Nowadays, he thinks of it as a chain reaction: music, his friendship with Cave, the gum, the park, the documentary. It’s all connected, and has led him from being an egoist to someone with open eyes. He doesn’t aspire to anything more. He has reconciled with himself. “They have been intense years,” he says, and strokes his dog, who has been at his feet the whole time and suddenly, is looking at him — one would swear, with a certain amount of worry. “The park opened my heart to something I never thought imaginable. I didn’t expect to get something back, you know, I just wanted to do it. I think we all learn at some stage that giving has great repercussions. When you approach the world in an open way, it has a knock-on effect. I’ve been negative a lot of my life, you know, fuck. I still can be, but I try not to be so critical of humans. I think I can be quite mean at times. But I don’t feel as mean as I used to. The meanness has sort of left me.”

When he stops talking, the dog puts her snout between his legs. “What’s the matter, sweetheart? It’s time to go home, isn’t it?” Ellis says to her. It’s been almost three hours since he showed up at the pub, but it seems like if it were up to him, he could stay there all night, drinking club soda and chatting. But the dogs are already on their way to the street. Yes, it’s time to go home.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.