The Spanish illustrator who dissects politics for ‘The New York Times’

Pablo Delcán translates complex ideas with simple brushstrokes, and he must do so at top speed

When he was in school, Pablo Delcán had difficulty passing his exams because he would answer questions with just one sentence. “I was good at reading a story and summarizing it in just three words, but that hurt me. Now it’s what sets me apart as an illustrator. I read something complex and I know how to communicate it in a simple form, in a form that invites people to be curious about it,” he says.

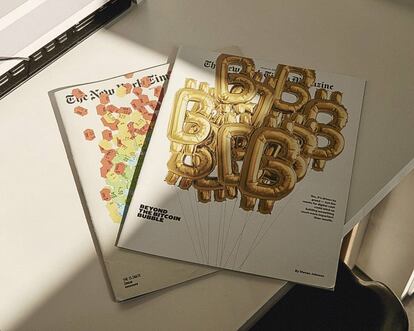

It took years before his impediment became his gift, and now he is one of the leading graphic designers for the op-ed section of The New York Times, where he makes some of the most striking covers for the magazine. It recent months he has illustrated an opinion piece by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei entitled Capitalism and ‘Culturicide’ and used simple strokes to depict the famous confession of a government official exposing the delirium of the Trump administration.

And he’s done so in record time. “They call me around noon or 1pm, the sketches have to be ready at around 3pm or 4pm, and everything must be done by 6pm. At 9pm the online version is up, and the next morning the paper is out,” he explains. Delcán remembers how, when he was employed at Penguin Random House Mondadori, he used to complain about the slow-moving place of the publishing world.

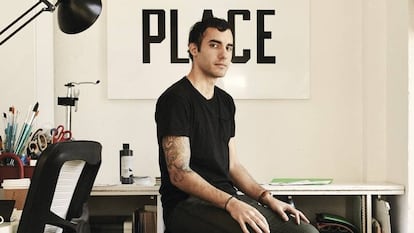

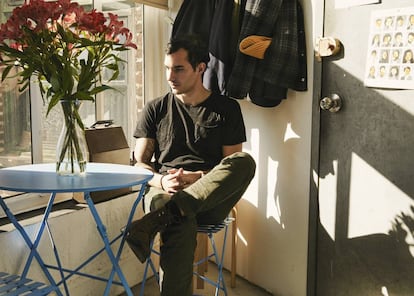

Delcán now works from his studio in New York’s Lower East Side, where he runs his own company Delcan & Co. It is basically a wide corridor crowded with a beautiful array of his own artistic references, from Spanish painter Francisco Goya to Mark Rothko. Also on display is The Abbey of Crime, a cassette video game created by his own father, the animator and filmmaker Juan Delcán. There are also some of his own creations: sculptures of hands and eyes, various clocks (none of them set to the right time) and products for clients (concert posters for Lorde, Sigur Rós and Green Day, and book covers for Alejo Carpentier and Vladimir Nabokov).

It’s a modest place, but it is bathed in a soft light that could be called inspiring if it weren’t for the fact that Declán doesn’t believe in that word. “When you don’t have the option to not be inspired, you don’t have a choice except to do the work,” he says concisely, with the same ease that he defines his work as a translation: he analyzes original texts and converts them into images. And although this characterization seems to take away merit from his work, it actually conceals a necessity for documentary rigor that forces him to open his eyes to reality and adhere to the original material without letting his own opinion leak through; it also reveals a particular philosophy about his discipline that almost sounds self-damaging. “Design, in some ways, acts as an elitist format. When something is designed it has reached a community that tends to push people away instead of inviting them in. I’m interested in the opposite,” he says.

Delcán favors an uncontrived, unbiased design, one that avoids wily embellishment. In the end, that’s what appeals the most to him about living in a city as aesthetically anarchic as New York. “You can define it as a city that is ugly by default, but that’s what I like the most about it. The most interesting moments of how a culture represents itself occur when the designer is not present.”

Delcán, like many millennial Spanish immigrants, has never worked in Spain. “I’ve been looking for work in Spain now, but I’m not having any luck,” he says, despite the awards he has been receiving and the fact that he’s already appeared on the Forbes list of 30 top artists under 30. When he talks about his work he finds it difficult to do so in Spanish. It’s true that his case is peculiar. Born in Madrid in 1989, his parents moved to California when he was five years old. Two years later they divorced and he relocated to the Spanish island of Menorca with his mother, the artist Nuria Román. With this adolescence “in a bubble,” and always surrounded by creativity (his grandmother had a ceramics studio and his little sister is the actress Olivia Delcán), he found his idea lab inside a barnyard where he rehearsed in a band with his friends. He played the drums and was in charge of marketing: posters, logos, album covers…

It was rock that beckoned him to New York City at just 18 years old, where he played with his band, Belladonna. But he also enrolled in graphic design studies at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan, where his father was a teacher.

Today he has become a professor of animation at the same school, and for a little more than a year, he has also been a father. “It has changed everything, but for the better,” he says, noting that it has made him prioritize his attention and not waste time with irrelevant projects. And although he hasn’t avoided the temptation to design a few toys for his son, he prefers not to fall into the habit of a designer fatherhood. “Luckily my cousin, who lives in Madrid and has two kids, brings a full bag of used clothes for my son every time she visits. It includes clothes that used to be mine. We’re keeping tradition alive,” he jokes.

English version by Nell Snow.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.