The ongoing legal battle over an 18th-century ghost ship

Chile and a treasure hunter are fighting over the cargo of a Spanish galleon that went down in 1770

It was King Ferdinand VI’s fault, for dying in 1759 without giving early notice. This triggered a change in fashion styles, and the new Spanish monarch, Charles III, imposed his own tastes. And so the glass products made at the Royal Glass Factory of La Granja (Segovia) quickly became passé, and therefore hard to sell.

The solution? Send them across the ocean to New Spain or to the Viceroyalty of Peru, where they were short on such supplies and where the focus was on their utility. The viceroy of Mexico, the Marquis of Cruillas, had written to Madrid on several occasions asking for glass elements for their horse carriages.

“Send them,” wrote Treasury Secretary Miguel Múzquiz. “But make sure sent items are only those with low demand and little appreciation from the Madrid public.” The problem has carried over to modern times, and is being currently considered by the courts in Chile.

Legend has it that on July 23, 1770, off the coast of present-day Chile, a sailboat named the Gallardo sighted the Oriflama, a ship carrying a cargo of glass products. When the latter vessel did not respond to their cannon salute, the local sailors boarded the Oriflama and found the entire crew either dead or dying. They hurried back to their own boat to alert the captain, Juan Guillermo de Ezpeleta, but the Oriflama, with nobody at the helm, continued along its aimless route and disappeared into the mist. To this day it is known as the “Ship of the Dying.”

Historical records, however, indicate that the Gallardo found around 70 survivors suffering from scurvy out of an initial crew of 200, but that a tremendous storm prevented their rescue.

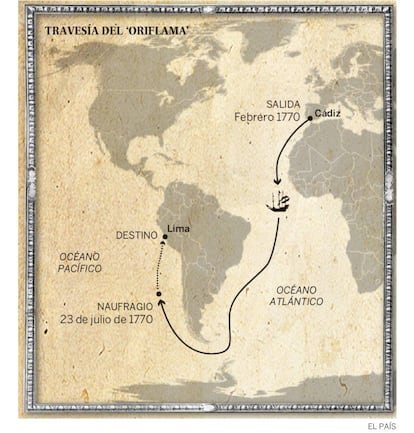

And so the galleon, which was traveling under the sponsorship of one Jerónimo Ustáriz y Tovar, who had purchased the entire glass production from the Spanish king for 1.29 million reales (the equivalent of around €8.3 million at today’s exchange rate), was swallowed up by the Pacific Ocean, along with the 450,000 glass items in its hold. Researchers believe the Oriflama went down around 250 kilometers from modern-day Santiago de Chile, off the beach of la Trinchera.

Twenty years ago, a Chilean company named Oriflama SA found the wreck, triggering a legal battle between the treasure hunter and the government of Chile. “There were chandeliers, optical instruments, mirrors, dining sets...” says Paloma Pastor, director of the Royal Glass Factory in La Granja. Most surviving original pieces produced by this factory, which was a supplier to the Spanish crown, are currently on display at museums in Spain and the Americas. “Finding the cargo was a historic and unprecedented discovery,” says Pastor.

The Oriflama was an enormous ship, over 41 meters in length. Besides its precious cargo, it carried 176 crew members and 38 passengers. It was originally built at the French shipyard of Toulon, but captured by the English. The Spanish in turn took it from the English, and the Spanish crown sold it to the businessman Ustáriz. The ship was rechristened Nuestra Señora del Buen Consejo y San Leopoldo, but never lost its alternative name of Oriflama.

After loading 1,741 crates with the glass pieces, which were protected with straw and cloth and encased in leather, the Oriflama left Cádiz in February 1770. After it sank, a few crates floated to the beaches of Curepto, where the parish museum still keeps them.

In 1999, the treasure hunting company Oriflama SA obtained a license from the government of Chile to begin exploration. Divers found, among other things, a piece of wood from a spruce variety that was used to make French ships at the time. Pepper seeds, glass items and metal pieces also turned up.

It was originally built at the French shipyard of Toulon, but captured by the English. The Spanish in turn took it from the English

In 2005, a court in Curepto granted the treasure hunter “right of ownership” over the wreck, but recommended reaching an agreement with the Chilean state. The latter denied the company the final license, based on an agreement reached by the National Archeology Committee. “The property of certain goods is not negotiable,” said a Chilean government spokesperson in a conversation with EL PAÍS.

José Luis Rosales, manager of Oriflama SA, disagrees. “We have rights based on a concept known as acquisitive prescription, which means that if nobody claims the cargo, it belongs to the one who found it. We placed ads in the newspapers [in Chile] and nobody claimed it,” he says.

The government admits that the law allows up to 25% of the discovered treasure to be ceded to foreign scientific missions, but not to national ones.“What we are asking now is to at least cover the costs of our investment and to be able to create a museum to offset the expenses,” says Rosales.

“We would like to take part in the research, but there is no relationship with them, which is a pity,” adds Paloma Pastor, of the Royal Glass Factory. “The wreck is worth it. There is nothing like it under the seas.”

Jerónimo de Ustáriz died without children

One might think that the rightful owners should be the descendants of Jerónimo Ustáriz y Tovar. But José Ignacio Vaillant y Hormaechea, a consultant and sixth marquis of Ustáriz, explains: “I am not a direct descendant of the man who chartered the ship, who was the second marquis of Ustáriz and who died without children. That is the truth. And I don’t think anybody is his rightful heir, not even those who make that claim [alluding to a Venezuelan family that claims to be descended from the shipbuilder.]”

Vaillant y Hormaechea, who is a history buff, says that Oriflama SA never got in touch with him. “We would have told them the same thing, but it is not enough to run an ad in a Chilean paper and feel that you have attempted to contact the descendants.”

This source adds that typically, these ships’ cargo often included up to 40% of smuggled goods, “so nobody can prove that he owns everything.”

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.