Will Spain ever legalize surrogacy?

Faced with a growing trend, politicians need to take a stand on the issue, but deep divisions prevail

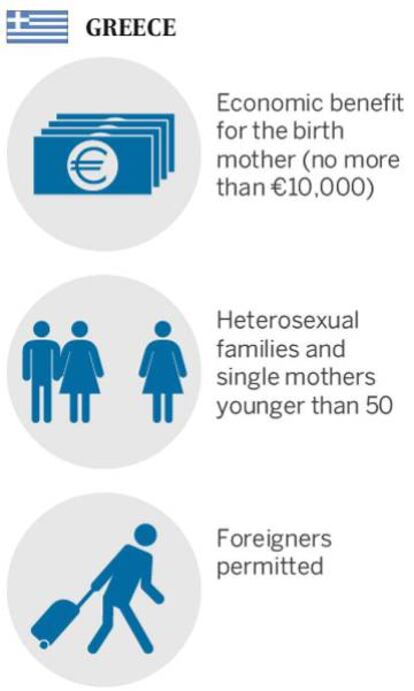

Once again surrogacy is a hot topic in Spain. Under the Assisted Reproduction Act, surrogacy contracts are legally void (although they are not explicitly prohibited, meaning that there are no sanctions for the parties involved). In recent years there has been a rise in the number of couples heading abroad to find a surrogate mother – to places like Mexico, Greece, Ukraine, Canada and the United States. Faced with a growing trend, political parties are being forced to take a stand on the issue – if they can ever overcome their own internal divisions.

Although no official figures exist, if the estimates are correct, international surrogacy has overtaken overseas adoption as the choice for would-be parents in Spain.

Spain’s political parties have been slow to react to a trend that shows no signs of going away. And so far, their responses have mostly served to reflect deep internal divisions over a thorny issue still largely unregulated.

Only Ciudadanos, the recently emerged protest party that grew out of Spain’s economic crisis and is now the fourth largest presence in Congress, has committed to a clear position.

It’s not right that people need to spend $150,000, take out a mortgage and go to the US in order to be a father or a mother

Ciudadanos leader Albert Rivera

On Tuesday of last week, Ciudadanos introduced a bill in Congress to regulate altruistic surrogacy. Under the proposed terms, only women between the ages of 25 and 45 holding Spanish citizenship or legally resident, from a stable socioeconomic background and with children of their own would be eligible to become surrogate mothers in Spain.

“Who are we to tell other people that they can’t be parents?” asked Ciudadanos leader Albert Rivera at a party rally on a recent Saturday. “Who are we to prevent someone from forming a family through clear, precise and altruistic regulation?”

The bill also envisions fines of up to €1,000 for minor violations, going all the way up to €1 million for serious infractions such as paying the surrogate mother for anything other than out-of-pocket expenses stemming from pregnancy and childbirth.

An uphill struggle

But Ciudadanos, which has 32 deputies in the 350-seat house, faces major hurdles in making its project a reality. None of the three other major parties in Congress – the ruling Popular Party (PP), the Socialist Party (PSOE) and Podemos – openly support surrogacy, and internal divisions exist within the parties themselves.

Assisted Reproduction Act

Article 10 of the Assisted Reproduction Act says that any contract arranging for a woman to carry a child, either for a fee or not, and surrender the child at birth will be legally void. Kinship will be determined by childbirth, meaning the woman who gave birth to the baby will be considered the mother by default, although it is possible to claim paternity rights “as per the general rules.”

Pablo Casado, a communications spokesman for the conservative PP, said on Monday the position of the party is one of “prudence.”

Irene Montero, who speaks for the leftist coalition Unidos Podemos, called surrogacy “the commercialization of a woman’s body,” although she also admitted that there are varying viewpoints within her political group, and that an internal debate on the issue is taking place.

Meanwhile, the main opposition party has just shut the door on the possibility of legally regulating surrogacy. At the PSOE congress in mid-June, the Spanish Socialists decided that they “cannot embrace any practice that means undermining the rights of women and young girls or reinforcing the feminization of poverty.”

During the campaign for party primaries earlier this year, the newly re-elected secretary general Pedro Sánchez had openly opposed surrogacy.

“I am not in favor of using the female body for prostitution, for trafficking or for surrogate motherhood,” he said.

Instead, Sánchez wants to “restore” assisted reproduction services in the public health system, eliminating “the limits established by the PP government.”

At the same time, there are segments within the PSOE that defend surrogacy, notably the groups Juventudes Socialistas (Socialist Youth Groups) and LGBTI.

But Ciudadanos will have more than other parties to contend with. Also on Tuesday of last week, around a hundred civil society representatives belonging to the Platform for Liberties asked congressional groups to vote against the bill.

Meanwhile, the Spanish Bioethics Committee, which answers to the Health Ministry, took a clear stand against surrogacy in mid-May, proposing an international regulatory framework that would ban this type of contract “in order to guarantee the dignity of woman and child.”

But the chances of the Spanish government securing an international resolution banning surrogacy globally are very low. The committee also suggested sanctions for surrogacy agencies in Spain. A recent surrogacy fair in Madrid was protested by feminist groups.

Facts on the ground

While politicians and experts debate the pros and cons of surrogacy, the facts on the ground keep piling up.

Hundreds of Spaniards undertake trips every year to fulfil their wish to become parents. If everything goes well, they will work with agencies of varying trustworthiness. These, in exchange for money, will hire women who are willing to undergo hormonal treatment, carry another person’s baby to term and promise to give it up after childbirth. These women are typically from poorer countries – Mexico, Ukraine, Thailand – though not always.

I am not in favor of using the female body for prostitution, for trafficking or for surrogate motherhood

PSOE leader Pedro Sánchez

The Swiss-based International Social Security Association estimates that every year, surrogate mothers give birth to around 20,000 children worldwide. Agencies and parents estimate that between 800 and 1,000 go on to live with Spanish parents, but there are no official figures.

There are numbers, however, for international adoptions by Spaniards, and these have dropped from 5,541 in 2004 to 799 in 2015. The Spanish Health Ministry offers several reasons for this fall, including better child protection in the countries of origin.

Instead of the international adoption process, which can take up to eight years, it seems that those wanting to be parents are more frequently opting for the quicker route and paying between €60,000 in Russia or up to €120,000 in California – one of 14 US states where the practice is legal.

Babies in limbo

The trouble starts when couples who go abroad –an association called Son Nuestros Hijos (They Are Our Kids) estimates there are 500 to 1,000 each year – register the newborns there, then return to Spain, where the kinship document must be validated.

In 2010, the Directorate-General of Registrars and Notaries allowed these children to be officially registered in Spain to ensure they would not be left in a legal limbo, but later court rulings have made this process more complicated.

“Children cannot be left waiting at the doors of a civil records office,” said Ciudadanos’ Rivera, acknowledging the problem. “It’s not right for those children not to get registered, or to have trouble doing so, depending on what province they live in. It’s not right that people need to spend $150,000, take out a mortgage and go to the US in order to be a father or a mother.”

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.