Spain struggles with surrogate pregnancy issue

Practice is illegal here but debate rages over whether surrogacy is a right or a form of exploitation

Cristina, 40, spent months running from one medical appointment to the next; doctors gave her hormones, she had her ovaries punctured, and she took pills that triggered migraines, vomiting and emotional imbalance. She cried when they told her that, once again, none of it had worked: she still wasn’t pregnant.

The few facts Cristina knows about the woman who gave birth to her twins in January are the following: her name, her age, her nationality (Albanian) and that she is married with two children of her own. “You really need courage to do that for another person. I don’t know whether the compensation really covers it all… I’m sure there must be some element of goodwill, to put their bodies at risk like that,” says Cristina.

Cristina chose to have limited contact with the surrogate mother. She only met her twice: once last February in the courthouse in the Greek city of Thessaloniki, where they initiated the legal process underpinning their joint pregnancy project. The second time was in the hospital, when the babies were born. The surrogate mother gave up all rights to the children that she carried. Their parents are Cristina and her husband, David.

Hopeful parents are forced to navigate a lucrative and opaque industry that often operates on the edge of legality and ethics

Hundreds of Spaniards undertake similar trips every year. Surrogacy is not legal in Spain, so those who want to work with a surrogate mother must go abroad. If everything goes well, they will work with agencies of varying trustworthiness. These, in exchange for money, will hire women who are willing to undergo hormonal treatment, carry another person's baby to term and promise to give it up after giving birth.

These women, most commonly, are from countries poorer than Spain. Throughout the process, the hopeful parents are forced to navigate a lucrative and opaque industry that often operates on the edge of legality and ethics. It’s a global process which has, in turn, created a global debate over whether or not the practice should be regulated, and if so, how.

The Swiss-based International Social Security Association estimates that every year, surrogate mothers give birth to around 20,000 children worldwide. Agencies and parents estimate that between 800 and 1,000 go on to live with Spanish parents, but there are no official figures. There are numbers, however, for international adoptions undertaken by Spaniards, and these have fallen from 5,541 in 2004 to 799 in 2015. Several reasons explain this drop, says the Spanish Health Ministry, including better child protection in the countries of origin.

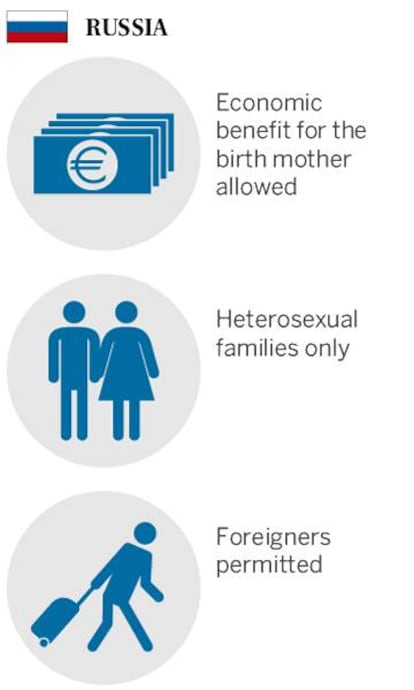

Yet, if the estimates are correct, international surrogacy has overtaken international adoption in popularity. Instead of the international adoption process, which can take up to eight years, it seems that those wanting to be parents are more frequently opting for the quicker route, and paying between €45,000 and € 60,000 in the Ukraine or Russia or up to €120,000 in California – one of 14 American states where the practice is legal.

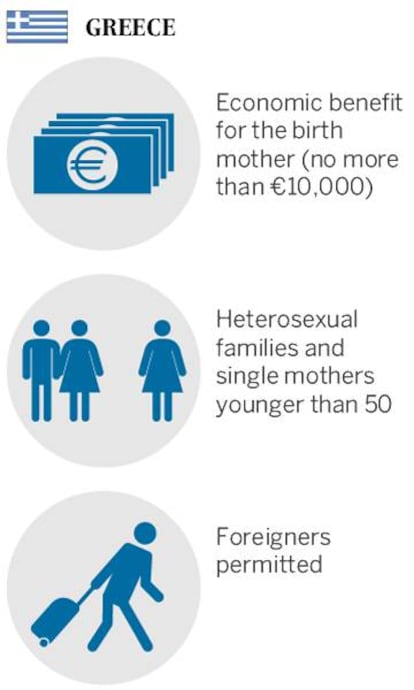

Every country has different legislation. Ukraine, for example, only allows heterosexual couples to use surrogates. In Canada, the United Kingdom and Portugal, surrogacy is only allowed in the altruistic sense, meaning the surrogate mother receives no direct economic benefit. And the latter two countries only let nationals use surrogacy. India, a former worldwide power in surrogacy, has vetoed it for foreign couples, and is on the verge of making it illegal for economic profit. Mexico too, particularly the State of Tabasco, has recently restricted surrogacy laws.

Fears of exploitation also caused Thailand to restrict the practice. In 2015, the government limited it to Thai citizens after the “Baby Gammy” story hit headlines and scandalized the nation. An Australian couple hired a Thai woman to carry their twins. But when they discovered that one of the twins had Down syndrome, it was too late for an abortion. In any case, the surrogate mother didn’t want one. When the Australian parents came to pick up their children, they only took the one without Down syndrome and left the other child behind. Months later it was revealed that the Australian father was a convicted child sex offender who had gone to prison in 1997.

The Thai case is uniquely horrifying, but it is a good example of how the rights of the surrogate mothers and the children they carry can be left to the whims of the parents, as well as the clinics and agencies in the corrupt and poor countries where they often operate. This lack of protection provides arguments to those who think the practice should be regulated, as well as to those who want to prohibit it.

In Spain, surrogacy has become a hot topic again. Among political parties only Ciudadanos, the fourth largest presence in Congress, has committed to a position, which is to regulate altruistic surrogacy.

“The best solution to avoid abuses is to legislate it. It’s like organ transplants – regulating the legal practice gets rid of organ trafficking,” says Pedro Fuentes, president of a pro-surrogacy parental association that brings together around 400 families, Son Nuestros Hijos. Fuentes is a gynecologist and alongside his husband, he is also the father of a six-year-old boy who was born in California to a surrogate mother. He gets emotional when he tells the story of how he met the surrogate mother and the warm relationship they developed. He said that her own ethics also guided the process, as she had decided to use her body as a surrogate to help a gay couple.

The association itself has a code of ethics and recommends not trusting “agencies that don’t let you meet the mother, which guarantee results, and which offer package deals saying you won’t have to worry about anything.” Also, they suggest that parents work with a woman who has already given birth. The association certainly makes the case for altruism but it is also open to economic compensation.

Surrogacy is illegal in Spain, so those who want to work with a surrogate mother must go abroad

“It’s necessary to recognize the effort that a pregnancy entails for the mother. They have to wear maternity clothing, lose the opportunities to do other things… payment should be enough that it’s not an insult, but not €100,000 either to avoid a push effect… it could be set by a national commission.”

The association asks: “When is a women being exploited? When you pay her or when you don’t?”

Alicia Miyares knows where she stands. She is a philosophy professor and a spokesperson for the feminist movement No Somos Vasijas, which in English means “we are not vessels.” It was created in 2015 when the debate entered the political realm. “I think that one of the strongest desires that anyone can have is the desire to have children. There are some really dramatic situations out there: women without wombs, perhaps because they’ve had cancer, and homosexual couples who can’t have children. How could I not understand their frustration? But I don’t think we should put desires over rights. Bodies are the limits of what can be bought and sold,” she says.

The line between altruism and capitalism can also be vague in surrogacy. “We know that countries that allow it for altruistic purposes cannot stop reproductive tourism, and that it’s impossible to avoid under-the-table payments,” she adds. For her, the best option is to streamline the adoption process, which “allows people to verify the suitability of the guardians. In surrogacy, the parents don’t have to pass through any filters.”

Petra de Sutter, a member of parliament at the Council of Europe, is an expert in assisted reproduction. In October she wrote a report on surrogacy for the 47 countries on the Council, which ultimately voted against her recommendation to create international guidelines related to surrogate pregnancies. She argued that the practice should be restricted and only allowed in altruistic cases. “In Belgium we have 20 years of experience with this. It isn’t done for economic ends, foreigners aren’t allowed, there are ethics committees and it is necessary to comply with a number of criteria. Situations exist, for example, in which a woman wants to help her sister become a mother,” she said.

Altruistic cases are rare however, and commercial surrogacy makes up about 98% of the cases worldwide. The United States is the most expensive country but it also offers the most guarantees. There, it is all regulated. Yet even in the United States, which is rich and backed by a solid legal system, feminist groups denounce the vulnerability of surrogate mothers. Kelly Martinez, a 32-year-old American baker, has had eight babies. She’s had three of her own and five for parents who hired her. “I wanted to help others, knowing that this miracle happened thanks to me,” she explains on the telephone. “The first two times I worked with fantastic couples.”

Her third and final surrogate pregnancy was with a Spanish couple. Her voice changes when she speaks about it. Everything was going well until they discovered that “instead of having a boy and a girl like they wanted, I was going to have two boys,” she says. “They started to treat me differently, they stopped asking how everything was going and I started to get worried about the babies. It still breaks my heart. I still regret doing it,” she said. She had pre-eclampsia, which can mean serious complications. “The doctor said we had to get them out soon because if not, either the babies or I weren’t going to get out of this.”

The parents, she said, accused her of wanting to give birth early so she could collect her money faster. “When I saw the man’s reaction when he found out they were two boys, I was afraid that they wouldn’t want them and they wouldn’t come collect them. It was really hard not to know if they babies were going to be OK. I don’t know anything about them.”

In the end, the Spanish couple did pick up the boys but they still owe $10,000, which debt collectors are now trying to get from Martinez. According to her, they are saying she violated the contract by getting an X-ray without their authorization – something which she denies – so they won’t have to pay. Nearly a year later she suffers from diagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder and doctors have recommended that she have her tubes tied due to the complicated delivery. “I thought I was protected by the agency’s lawyers, but no,” she says.

Some contracts are very long-winded and brutally direct. One of the pages of a 2015 contract signed in California and released by an activist says the following regarding “compensation [to the surrogate mother] for the loss of an organ as a direct consequence of the pregnancy:” “Removal of the Fallopian tubes or of ovaries, $2,500 each,” “Uterus removal, $5,000.” The contract also stipulates that the parents, not the surrogate mother, are free to decide to terminate the pregnancy if something is going poorly. It also included that the mother cannot have sex during the pregnancy, that she must stay within state boundaries, cannot swim in the sea and cannot ingest saccharin.

Martinez got in touch with one of the best-known feminists who oppose the practice, Jennifer Lahl. She leads the Center for Bioethics and Culture Network in California, and is one of the founders of the international platform Stop Surrogacy Now. In October she was in Madrid for a bioethical conference, hosted by the Catholic Foundation Jérôme Lejeune. The conference clearly proved that the subject of surrogacy is able to bring together diverse groups.

Lahl uses irony when she responds to the argument that regulation will stop abuse: “We know that there’s a black market for organs, human trafficking networks… so let’s regulate them to protect people.” She also doesn’t believe that altruism is an option: “Think about how many women want to go through a pregnancy for a stranger.” She uses the example of Canada, which follows the altruistic rule but allows the parents to compensate the woman for the costs of the pregnancy. “There are a lot of loopholes,” she says, adding if a woman does it for a relative, the situation can end up being “a disaster.”

The line between altruism and capitalism can also be vague in surrogacy

The parents’ budget is an important criteria when it comes time to choosing the country where they will find the surrogate mother, and agencies know this. Didac Sánchez, 24, leads Subrogalia, one of the most well-known agencies around. Its headquarters are in Barcelona but she says she is picking up our call in Kiev, the new surrogacy capital, where there are hardly any regulations.

“I’m going to recommend you the country that best adapts to your needs. If you’re heterosexual, I’ll tell you to go one place, if you have HIV, I’ll recommend another, but I’m going to make your dreams come true,” she says. The agency has offices in several countries and they’ve just opened a new one in Greece, an attractive country because it is in the European Union and a judge has to authorize the process, something which gives parents more security. She is convinced that this is Greece’s year: “It will be a real alternative to the United States. Why would I spend $120,000 if it could be $65,000?”

Sánchez says her clientele is not only Spanish; she also works with “Italian, Chinese, French and German” parents. As for the surrogate mothers, she explains that “we recruit them in Russia and Ukraine. In Ukraine you can advertise in the press. Instead of placing an ad about Coca Cola, you put one in for surrogate mothers. In Greece there are clinics that bring the women directly to you.”

For Cristina and David, everything went well and they went through the entire process through Subrogalia. Even so, there are at least three families that have sued the company for breach of contract. “Some of my clients have gone into debt until the year 2030 to pay for this process,” says the lawyer Joana Marín. “When they arrived in Mexico they discovered that the embryos hadn’t even been sent over from Spain.”

The best solution to avoid abuses is to legislate surrogacy

Pedro Fuentes, pro-surrogacy activist

Another risk that hopeful parents face is becoming entangled in the bureaucracy surrounding surrogacy. There is no international legal framework regarding surrogacy. In 2015, the European Parliament condemned the practice because it “undermines the human dignity of the woman since her body and its reproductive functions are used as a commodity.” For now, only The Hague Conference, the multinational organism for international law, has a group of experts analyzing the legal viability of establishing a common framework for surrogacy.

José Borrallo, a 43-year-old civil servant from Spain, is in an uncertain situation of his own. He has started a legal battle for his two-year-old son, born in the Mexican state of Tabasco, to be recognized as a Spanish citizen and as his legal son. Borrallo fears that his boy will get lost in the system if something happens to himself. Today, as far as the law is concerned, the boy is Mexican.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.