Revenge of the shy kids in class: How Elon Musk and co. went from nerds to bullies

The richest man in the world, along with Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg, exemplifies how the most diligent students, upon reaching the business elite, didn’t bring about a new era of empathetic leadership. Instead, they adopted the harsh tactics of those who once made their lives miserable

A new kind of antihero is taking the world by storm: the evil nerd or nerd-turned-villain. These figures, spiritual heirs to Lex Luthor and classic James Bond villains, are increasingly associated with real-world personas — most notably Elon Musk, the man who launches rockets into space while laying off hundreds of thousands of U.S. civil servants. A growing chorus of voices suggests that the most dangerous tyrants may be those who once endured the sting of adolescent marginalization. Welcome to the rise of a new order: the nerdocracy?

Moira Donegan, writing in The Guardian, argues that we’ve entered the age of the narcissistic nerd. She describes Musk as former shy, studious kids who now “insists on discarding solemnity and being ostentatiously irreverent and carefree as he destroys people’s lives.”

On Medium, George Dillard adds that even the more reserved figures in this cohort — like Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg — believe the time has come for their final ascension, made possible by the rise of Donald Trump. According to Dillard, this is why Zuckerberg has put aside any inhibitions and now dresses like a crypto bro, flaunting a $900,000 watch: they are no longer pretending to be regular people.

On her podcast The Comment Section, Reagan Conrad expresses uncertainty about Elon Musk’s legion of bright young followers — will they save America, or simply “take it over”?

Meanwhile, some conservative commentators strike a more optimistic tone. Analysts like Nolan Finley and Brittany Chain suggest that the political ascent of billionaire tech entrepreneurs might not spell disaster, but could instead offer the radical solution to a “broken” U.S. economy.

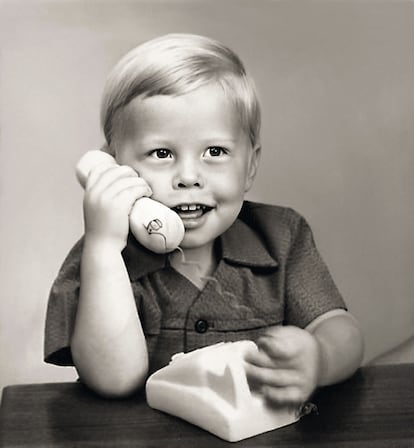

Filmmaker Lars Von Trier said that you don’t need to have grown up in Texas, Wyoming, or Montana to understand U.S. student culture. In a way, we’ve all attended an American high school — somewhere within the vast, globalized version of the United States delivered to us through TV shows, movies, music, comics, and video games. We all know the tropes: proms, cheerleaders, and tribal labels like jock and, of course, nerd.

As scientist and tech expert Burr Settles has shown through a statistical analysis of hundreds of thousands of social media interactions, the once-marginalized nerds have now ascended to the top of the social food chain.

Burr Settles set out to settle, once and for all, the true distinction between nerds and their neighboring tribe: geeks, with whom they’re so often confused. He even questioned which label best described his younger self — nerd or geek? His conclusion: geeks are collectors; nerds are scholars. Geeks gravitate toward video games and Japanese comics; nerds toward chess and Sudoku. Both might be seen as socially awkward, but there’s a key difference — geeks are introverts, while nerds are arrogant entrepreneurs whose self-esteem thrives on the contempt of others. Sheldon Cooper? A geek. Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg? Nerds.

Until the mid-1980s, both would have fallen under the (much broader) label of “freaks.” However, around that time, coinciding roughly with Ronald Reagan’s conservative counter-revolution and the release of films like The Revenge of the Nerds (1984), nerds began to emerge as a distinct tribe — an insurrectionary elite ready to challenge the high school class system, while geeks stayed in their rooms playing with their monsters.

Trey Parker, co-creator of South Park, captured the reversal with brutal clarity: he (a self-proclaimed professional nerd) now makes millions, while many of the high school athletes who once tormented him flip burgers at McDonald’s. Bill Gates took it a step further in a high school speech 14 years ago, famously advising: “Be nice to nerds. Chances are you’ll end up working for one.”

There’s something deeply satisfying — even redemptive — about that sentiment. The tyrannical logic of high school doesn’t extend into the real world. The last shall be first. Intelligence, ambition, and persistence are rewarded; brute force and bullying are punished. As early as 1990, Leonid Fridman was making the case in a widely read New York Times op-ed: “America needs its nerds.”

For Fridman, genuine talent with transformative potential was to be found in those who devoted their formative years to self-directed learning, nurturing their intellectual and technological curiosity, and thereby stepping into a new world: the knowledge economy. We already live in that world.

In Source Code: My Beginnings, Bill Gates recalls attending a high school dominated by anti-intellectualism. Students who were different — those who studied hard, who explored unconventional interests — were met with contempt. Yet, according to Gates, it was precisely this generation of outcasts who would go on to become the technological pioneers of Silicon Valley, the architects of the Third Industrial Revolution. They triumphed — and in doing so, imposed, at least in part, their values.

Now recast by circumstance as the emblem of the “good” guru —philanthropic, socially conscious, the moral counterweight to the archetypal evil nerd — Gates draws a clear line between the nerds of his era and the modern urban tribe descended from them: the tech bros, as if one thing had nothing to do with the other.

In Source Code, he criticizes tech bros for their “superficial solutionism” — the belief that every problem has a simple, technological fix. Technology, Gates argues, is “neither a hero nor a villain.” It requires direction, philosophy, and a guiding narrative.

And the tech bros — with their political impatience, blind cult of efficiency, and uncritical predilection for technological “fetishes” like artificial intelligence and cryptocurrencies — have forgotten that true solutions and “authentic innovation” require subtle reflection and minds sensitive to nuances. This, Gates laments, is precisely what is missing from the “new” breed of nerds now entering political power alongside Elon Musk in the Trump administration.

Musk himself is a strange figure in the nerd subculture, even though he’s become a symbol of how nerds have now moved into the political spotlight. The son of Maye Haldeman — a model and nutritionist—and Errol Musk, an engineer and pilot, Musk had a quintessentially nerdy adolescence. His teenage years were marked by an obsessive love of computers and reading, a fraught relationship with a father he has described as “a terrible human being,” and relentless bullying. Walter Isaacson’s biography highlights a defining episode from this period: Musk spending days in the hospital after a particularly brutal beating by classmates — a story that cements his nerd credentials.

The 2022 Prime Video documentary series Elon Musk: Superhero or Supervillain explored these formative traumas and the ways they may have shaped the world’s richest man. In The New Yorker, historian Jill Lepore completes the portrait of this unique individual, drawing parallels to American industrialists like Andrew Carnegie, innovators like Thomas Edison, and even dangerous villains like Dr. Manhattan from Watchmen.

“Are you sincerely trying to save the world?” comedian Stephen Colbert once asked Musk during an appearance on The Late Show. Musk, living up to the introverted and socially inept nerd he perhaps still is, stammered that he was just trying to do some good. Colbert replied: “But you’re trying to do good things and you’re a billionaire. That’s either superhero or supervillain. You have to choose.”

For Jill Lepore, that is Musk’s great dilemma. He still doesn’t know whether he wants to be the universal benefactor who will solve all the world’s problems, or if he’ll settle — like Lex Luthor — for channeling his old nerd resentment and flaunting his wealth and omnipotence in the faces of the jocks who used to beat him up in high school.

These are, in the end, contemporary dilemmas for which we won’t find answers in Revenge of the Nerds — the film that first brought nerds into our lives to stay.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.