From Gutenberg to Elon Musk: History, power and technology

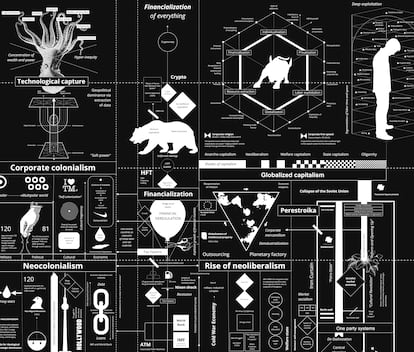

‘Calculating Empires’, the award-winning work by Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler, is a fascinating map that explores the interconnections between control and technological advances, showing how they have been leveraged as tools of domination

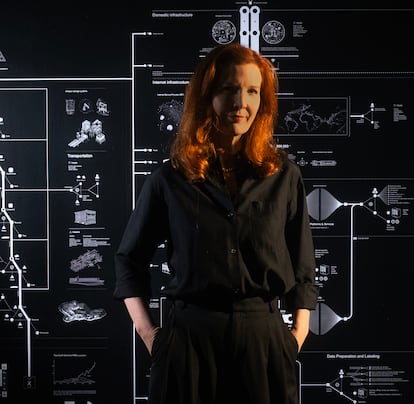

Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler are no ordinary cartographers. Crawford advises governments worldwide on AI development and governance, and has been on constant standby since the rise of figures like Donald Trump and Elon Musk. In fact, the Australian academic flew to the Spanish city of Gijón from New York for this interview, stealing a few hours away from an emergency summit convened by Emmanuel Macron in Paris. Meanwhile, Joler lives and teaches at the School of Fine Arts in Novi Sad, Serbia, where a revolution has just erupted. Their second project together, Calculating Empires, has just launched in Spain as part of Digital Machines: Technology, Industry, Society, the latest exhibition curated by Pablo de Soto at the LABoral Center in Gijón.

The subtitle of Calculating Empires is A Genealogy of Technology and Power Since 1500. “It provides us with a kind of Rosetta Stone to critically interpret the last 500 years of Western imperialism and the new forms of imperialism led by Donald Trump, along with techno-oligarchs like Elon Musk, as well as Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping,” writes the Catalan architect Olga Subirós. “This work is essential for those seeking to understand the dynamics of power and technology that have shaped, and continue to shape, our world without the world.”

Its original version, rendered in black on white, will be on display starting February 21 at Matter Matters: Designing with the World, an exhibition curated by Subirós at the Museu del Disseny-Dhub, featuring over 600 pieces from the collection alongside several contemporary works.

The work is a 24-meter-long, three-meter-high map, filled with thousands of illustrations and detailed texts, spanning centuries of expansion, conflict and colonization. It explores how technological advances have historically been used to centralize authority and exert control. It is a visual essay designed to understand the interconnections, patterns, and dynamics that define the systems of control and exploitation hidden beneath our digitalized existence.

“In the 21st century, where democracy, industry, and the digital realm are increasingly interconnected, Calculating Empires questions the current architecture of innovation processes, arguing that the design of the digital machines for the future must consider long-term environmental and social consequences and opt for fair, ethical, and sustainable technologies,” says De Soto.

Thinking in systems

Crawford and Joler met 10 years ago at the Bellagio Center of the Rockefeller Foundation. Mozilla had brought them together for a workshop with a group of intellectuals to discuss rebuilding Alexa, Amazon’s AI. “Vladan and I were the only ones who realized that it wasn’t enough to rebuild the hardware,” Crawford explains over breakfast at the Parador de Gijón. “We couldn’t focus only on the algorithmic or interface layers. We had to describe the enormous infrastructure that supports it all, and makes it possible on a planetary scale, at an enormous environmental cost.”

It was the beginning of a relationship based on a shared obsession: mapping how technology has been used as an instrument of imperial power, with infrastructure and political economy as its central themes.

It was what you might call a match made in heaven. Joler had long been trying to break the invisibility of infrastructures and technological “black boxes” through visual diagrams such as The Facebook Algorithmic Factory under the umbrella of Share Lab, alongside writing essays on the new extractivism in collaboration with Italian thinker Matteo Pasquinelli and the formidable Catalan artist Joana Moll. Meanwhile, Crawford was a principal investigator at Microsoft Research in New York and co-founder of the AI Now Institute at New York University.

Their first collaboration was Anatomy of an AI System, where they traced the “field-to-table” journey of Amazon’s smart speaker, which is now part of MoMA’s and the Victoria & Albert Museum’s collections. Shortly after, Crawford published one of the foundational books on the subject: Atlas of AI. In it, she examines the AI supply chain in depth, calculating the environmental toll of lithium mining and other materials for hardware production, the energy consumption of data centers, and the labor exploitation concealed behind the alleged automation.

It took nine years to produce Calculating Empires, funded by the Prada Foundation. This year, it was awarded the European Union S+T+ARTS Award for Innovation in Science and Technology.

Artists have often drawn inspiration from large historical frescoes and tapestries — such as The Bayeux Tapestry or Aby Warburg’s Atlas — but Calculating Empires stands out for its scale. “Right now,” Crawford notes, “the power of technology is about large-scale accumulation.” This is most vividly embodied in Elon Musk’s growing empire. His companies — Tesla, SpaceX, The Boring Company, the platform formerly known as Twitter, and Neuralink — give him control over a fleet of interconnected, extractive infrastructures that expand under the guise of progress, all while destabilizing ecological, political, and social stability.

An unexpected revolution

The protests began in November after the roof of the Novi Sad train station collapsed, killing 15 people. On January 31, 2025, the day the exhibit opened in LABoral, thousands of students began an 80-kilometer march from Belgrade to Novi Sad. The cities they passed through greeted them with clothes, food, and cheers. On February 1, three months after the tragedy, protesters blocked the three bridges in Novi Sad, commemorating the victims and demanding political accountability. Everyone expected the government to declare martial law. Instead, Prime Minister Milos Vucevic resigned. A few days later, Vladan was able to fly to Barcelona to inspect the facility, though his thoughts remained in Serbia with his students. They had overthrown the city government, but not the president.

Unlike the Arab Spring or movements like Spain’s anti-austerity movement 15M, there’s a strange information vacuum in Serbia. Even social media offers no real-time updates on what’s happening. Is there a government blockade, or have the students themselves withdrawn from the networks, viewing them as tools of oppression? Joler points out that something much stranger is occurring: activists have changed their relationship with the media. They don’t hate them or fear them. They simply don’t care about them, he says.

“The government in Serbia did everything to control television, newspapers. They said that this was the main media battle, and over the last 12 years they have implemented many different techniques to react and intervene in the internet sphere,” he explains. “For example, every time you write something, they have obviously paid people, making comments supposedly fighting hate speech. It has been like this for so long that people no longer pay attention to them.”

Serbians have also found new ways to communicate. “I don’t consume information from traditional media anymore,” says Joler. “I am still involved in the information space, but it is not through the media, or Instagram, or Twitter. We have started connecting in a more organized way between peers, avoiding the algorithm.” Students now communicate primarily in person and through encrypted messaging apps like Viber and Signal, favored by Edward Snowden. “You have assemblies with hundreds of teachers, but nobody realizes that organizing a group on Signal is a political act.” Cryptography has reached the mainstream.

Followers and likes have been replaced by real-life actions: marches, assemblies, and universities. The effect is very different. Joler says that the first protest began as an explosion of emotional pain that turned into rage. The students shouted and painted a building red. Then they called for 15 minutes of silence. “This kind of meditative process transformed the anger into something more meaningful,” says Joler. John Berger once said that the function of protest isn’t to change the tyrant but to change the protesters. Joler believes that the collective grief shared in silence became a cathartic event, changing the nature of the movement. In their togetherness, grief gave way to a strange form of happiness.

And care. A brigade of teachers has been formed to ensure the safety of the students, who also have their own security. “Nobody knows anything about security, but after three months, they know how to move around the street, how to protect themselves from being hit,” says Joler. They’ve established protection patrols, with circles of safety within circles. It’s not just about shielding from physical violence; they also seek to protect the silence itself. They have protocols to guard against external propaganda campaigns. They don’t want to project themselves outward; they want to protect the new bond they’ve created above all else.

They don’t have a concrete ideology. “The student assemblies are trying to protect themselves from any kind of political influence,” says Joler, “even from NGOs. The movement is highly political, in the sense that they want to bring down this corrupt government, but they are protecting this kind of non-political space. It’s really strange. Nobody knows how it will end. It’s like some kind of post-post… political society.” When asked if the maps he has made with Crawford are of any use to him, he replies not much, at least for now.

“They are drawing ideas from the center of the map, like models of assembly organization,” he explains. “I think what we will see is a kind of post-post-post or meta level, where different parts of the map combine into something new.” Mapping how technology is used to enforce control helps us predict the behavior of law enforcement, but not the reaction of the people. This revolution has taken everyone by surprise.

“It was completely unexpected, and with those students,” he says, laughing. “We all thought this was literally a brain-rotten generation, in a completely apolitical sense, and suddenly it became as political as possible. In the end, human connection is unpredictable, even in a completely absurd context.” Does this mean the apathy we’ve seen in response to recent political events might be temporary, or that deeper movements are brewing? “The future is completely unknown,” he says, “but it is also weird, and beautiful, and strange, and scary, all at the same time.”

It’s an unusual conclusion from someone who has spent decades studying the forms of oppression that led us to this point. If Serbia can change the course of history, anything can happen. Looking at its latest map, it’s hard to imagine the end of empire. As Audrey Lorde famously said: “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Imperial domination

At the heart of Calculating Empires are, of course, von Neumann’s computations, which completely transformed the 20th century, and the Industrial Revolution. But there are also subtler and more insidious processes at play. For example, how the ability to measure the body and emotions evolves through calculation systems to become policies of discrimination, correction, and subjugation. Orthopedic technology was originally developed to correct the child who couldn’t sit up straight, use their right hand, or grow up in the “right” way, with straight teeth — or even straight emotions.

“Emotions were once seen as representations of morality, with four types of people manifesting in the color of your bile: yellow, black, white,” explains Crawford, pointing to the word “hysteria” on the map — a concept that spawns its own physical and chemical orthopedics, its own system of censorship and control. In the 20th century, emotion became something that could be measured, calculated, classified, medicated, and ultimately, monetized. “The concept of emotion as a natural phenomenon inherent to human experience is gone,” Crawford says. Enter Instagram psychologists.

The map begins in the 1500s in honor of two inventions. “There’s the printing press, which suddenly offers the ability to create global information networks,” Crawford explains, “and secondly, long-range navigation. The combination of the two gives rise to this sort of militarization of distance, the ability to colonize Indigenous peoples at much greater distances. And the ability to essentially codify knowledge and have that knowledge reach a much broader audience.”

Crawford, however, connects most deeply to the invention of artificial perspective, in the Renaissance, because it did what artificial intelligence is doing today “It’s changing how we literally see the world, see ourselves, and understand each other — a really important change in how we think about what ultimately becomes forms of capital and control.” Composing the map made her realize the importance of that influence across the centuries. She thinks we’re in a similar moment.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.