How Spain used “alternative facts” to bury environmental protest in 1888

Troops were sent in when miners demanded an end to open-air pyrite roasting at Riotinto copper mines

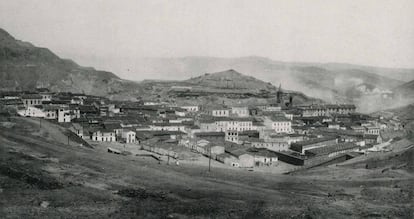

On the morning of February 4, 1888, thousands of farmers and miners, along with their families, took to the streets of Riotinto in the southwestern province of Huelva to demand better pay and conditions, including a call to end the practice of roasting pyrite in the open air, which produced deadly sulfur fumes.

Fifteen years earlier, the government of Spain’s First Republic had sold the land around Riotinto to a consortium of British and German banks. Miners, including children as young as 10, would extract pyrite from underground sources and then burn it in huge fires to extract copper. Some 900 tons were burned each day, creating clouds of sulfurous gases that poisoned residents and livestock, as well as destroying crops.

But what is probably the first recorded environmentalist protest in history came up against Spanish dragoons sent to Riotinto to quell the demands of anarchist-led labor unions. According to eyewitness accounts, cavalry from the Pavía Regiment opened fire on the demonstrators and then bayoneted them, killing dozens of men, women and children. But days later, a royal decree banned open-air burning of pyrite.

Many aspects of the protest were deliberately ignored or covered up by the newspapers of the day

Historian Ximo Guillén of the University of Valencia has studied the events at Riotinto 130 years ago, and explains that many aspects of the protest were deliberately ignored or covered up by the newspapers of the day.

“In 1890, the Royal Academy of Medicine concluded that there was no evidence of the negative impact of smoke [from the roasting process] on health,” says Guillem in an article based on his research published in Cambridge University’s Medical History journal. In December of that year, the government overturned the royal decree, allowing Riotinto’s owners, the Rio Tinto Company, to roast pyrite in the open air.

Guillem believes the Rothschild family, which bought into Rio Tinto in 1888, played a key role in persuading the Spanish authorities to allow the company to continue endangering the lives of miners and local people in the area. The Rothschilds had been involved in mercury production in Almadén, in central Spain since 1835, and had established connections at the highest levels of government and the state.

“After the events of 1888 in Riotinto, there was a determination to show that the smoke was not harmful to human health. I believe the arrival of the Rothschilds was decisive in that,” says Guillem.

He has found documents signed by leading academics of the time backing the view that the smoke was harmless and that the miners suffered no ill effects from exposure to it.

Two reports signed by leading academics suggested that the smoke helped combat cholera

But local landowners were opposed to the roasting process and began pressuring the authorities: in a letter to the regent queen of Spain, María Cristina of Habsburg-Lorena, the Anti-Smoke League described the process as “the most primitive metallurgical process, already discarded by science and banned in the civilized world.”

Two reports signed by leading academics suggested that the smoke helped combat cholera, ignoring monographs – such as one from 1848 – about the effects of metallurgical production on copper miners in Wales. By 1888 there was also demographic evidence that showed higher death rates in Riotinto.

Guillem says that the way in which the official version of events about Riotinto ignored the facts on the ground and other evidence is an early example of today’s so-called “post-truth,” or the “alternative facts” of US President Donald Trump.

“It connects with more recent cases, such as climate change denial or the links between tobacco and lung cancer,” he says.

English version by Nick Lyne.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.