Mining the metals that make the modern world go round in La Mancha

A firm wants to extract the rare earth elements used to power smartphones in Ciudad Real

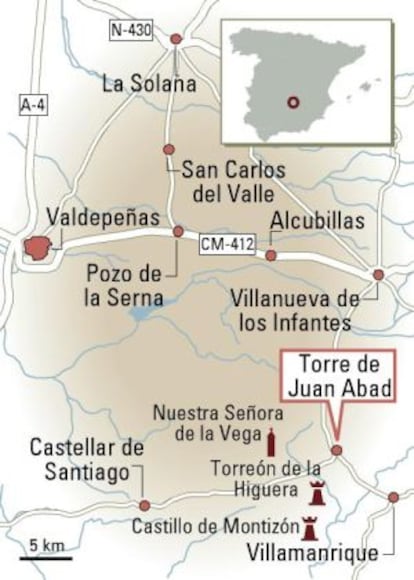

There isn’t a soul in sight at four in the afternoon in the streets of Torre de Juan Abad, in the heart of Spain’s La Mancha region. In this village of 1,100 inhabitants in Ciudad Real province, the only activity now going on is taking place inside the bar at the local seniors center.

The locals are trickling in for a cup of coffee, and when asked if they know anything about a group of minerals called rare earth elements (REE), they look puzzled and shrug. In a place where people just barely scrape a living from agriculture, nobody knows what their village has to do with iPhones, global geopolitics, or the trade wars between China, the European Union, the United States and Japan.

Europe should concentrate on one or two mines and on recycling a lot”

Christopher Ecclestone, Hallgarten & Company

But it has a lot to do with them. A Spanish company named Quantum Minería is planning to open a mine near here and extract REEs, a category that encompasses 17 chemical elements used to make hi-tech equipment ranging from computers to television sets, wind turbines and hybrid car batteries. Some of these minerals are also used to produce the magnets that make iPhone loudspeakers vibrate, powering their sound.

Most of the 110,000 tons of REEs produced annually in the world come from China – 86 percent in 2014 – giving it an enormous commercial edge that borders on outright monopoly.

Europe still lacks an open-pit REE mine, although there are a few projects in the pipeline. The one in Ciudad Real is modest in terms of size – it is expected to yield 20,000 tons of rare earth oxides with 10,000 further tons likely – but it stands out above the rest because of its high levels of praseodymium, neodymium and europium, three of the most coveted elements.

A geopolitical weapon

For years, Western powers lived off Chinese supplies with reasonable ease. But that was until 2010, when Beijing began using REEs as a geopolitical weapon, imposing strict export restrictions based on the argument that it was concerned about the industry's environmental impact. The deplorable state of the area around the city of Baotou, in northern China, is a good example of this: besides extraction, the region also processes the minerals, which is the most polluting part of the process. As a result, entire populations have had to be relocated because of air, earth and water pollution.

China managed to reinforce its tech industry’s position, and even got Japanese companies to move there to ensure supply. At one point Beijing threatened to cut off sales to Japan if Tokyo did not release the captain of a fishing vessel caught near Senkaku, an uninhabited island that is claimed by both countries.

The conflict ended in January when the World Trade Organization ruled in favor of Japan, the US and the EU, all of whom had filed a complaint against China. But by then the plaintiffs were already running scared. The US was additionally worried about its arms industry, as REEs are used for missiles, and the US government was investing in the search for alternatives to rare earth elements. In 2010, it reopened a large open-pit mine at Mountain Pass, California.

Meanwhile, new mines have cropped up in Australia and Vietnam. The EU has placed these products at the top of its strategy to ensure access to critical raw materials, and it wants to develop a plan to exploit mineral deposits in Europe under the EURARE funding program.

“There are potential rare earth element resources across Europe,” says British geologist and EURARE member Kathryn Goodenough. “Although the best-known ones are in Greenland and Scandinavia, there are many other areas under exploration, including Spain.”

Most experts cite the Norra Karr project in Sweden as the one that holds the most promise. This and the Ciudad Real site are at the most advanced stage.

The Spanish company Quantum Minería is now in the process of requesting an exploitation license, said sources familiar with the situation. Although the final area will be a lot smaller, the investigation phase surveyed thousands of hectares located between Torrenueva (population 2,900) and Torre de Juan Abad. Olive trees figure prominently on land that is used chiefly for agriculture, with the odd game preserve tucked in between the crops and the pastures, and a local cheese factory.

But in Torre de Juan Abad, which boasts an illustrious past – Baroque-era writer Francisco de Quevedo was exiled here in the 1600s – nobody knows anything about any mining project.

“I haven’t heard anything, and everyone drops by here,” says José Antonio, standing behind the bar at the seniors center.

The response is similar in the nearby village of Torrenueva, where several groups of retirees are sitting in the main square across from the 16th-century church. The men insist on talking about the antimony mine that shut down over seven decades ago, but seem to know nothing about a new one. Neither do local authorities, according to the municipal secretary.

We would love it if a mine opened up here”

José Luis Rivas, mayor of Torre de Juan Abad

But the Socialist Party mayor of Torre de Juan Abad, José Luis Rivas, is aware that an investigation project is underway and approves wholeheartedly.

“We would love it if a mine opened up here,” he says. “This is a very depressed area that lives exclusively off agriculture and has fewer and fewer jobs to offer. The young people have moved away. So if they were to create some steady jobs, even if it weren’t that many... That said, they would have to respect all environmental requisites.”

Environmental concerns tend to be one of mining’s great enemies – especially when it comes to REEs, which have such a bad pollution record. The Mountain Pass mine that reopened in the Mojave desert in 2010 had shut down 12 years earlier when it was discovered that an underground pipe was leaking out radioactive water.

Low radioactivity

There are indeed radioactive elements among the group of 17 minerals, including thorium and uranium. The Quantum project says the Ciudad Real site contains very small amounts of the former and nearly residual amounts of the latter. Also, the company in theory wants to make a rare earth concentrate, rather than separate the elements, which is much riskier.

“The challenge is to find ways to exploit those resources in a way that is viable from an economic and an environmental standpoint,” says British geologist Goodenough. She adds that many rare earth sites have “relatively low radioactivity” and thus do not present “major environmental problems” beyond the fact that an open-pit site is a visual blot, uses up a lot of water to make the concentrate, and produces waste that needs to be properly disposed of.

Two years ago, a project to research rare earth elements in the Galician mountains of Galiñeiro, in Pontevedra province, came to a halt because of technical difficulties and local opposition from a group that wanted the area to be declared a protected natural site.

But Goodenough believes that the greatest barrier to ensuring a supply of rare earth metals in Europe is making the mines profitable. The problem is that, no matter how crucial these elements may be for the continent, the prices are set by the ups and downs of the stock market and the supply-demand balance. And as a result of the fact that Chinese restrictions were eventually compensated for with new mines in other countries, increased recycling, and the use of alternative materials, prices are at rock bottom.

Projects of this nature require heavy investment, notes Christopher Ecclestone, a mining expert at New York-based investment bank Hallgarten & Company. “Europe should concentrate on one or two mines and on recycling a lot,” he adds.

Meanwhile, the Ciudad Real project – described as “promising” by Canadian analyst Ryan Castilloux – is trying to become one of these major European REE sites. Even in the best of cases it will still take time, since the paperwork can take anywhere between one and three years. By then, though, it is unlikely that residents of Torrenueva and Torre de Juan Abad will still not have heard about the “rare earth” surrounding their village.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.