The slave trade in Spain: thousands rescued from brothels and sweatshops

Since human trafficking became a criminal offense in 2010, the trend has become hard to ignore

A total of 5,695 people were released from slavery by Spain’s security forces between 2012 and 2016, according to the Interior Ministry. As victims of human trafficking, some were forced into unpaid labor, but the great majority were made to work as prostitutes.

Changes to the law have helped reveal the extent of the phenomenon, and allowed for a more effective approach in combating it. Sex slavery, for example, has become so lucrative in recent years that it now rivals the drug and arms trade in terms of prevalence and profit, according to Spain’s National Rapporteur on Human Trafficking – part of the EU network set up to monitor anti-trafficking policy in 2014. In 2016 alone, there were an estimated 23,846 people considered to be at risk, and in the case of sexual exploitation the majority were working in roadside brothels. Experts agree that serious debate on pimping is required if the situation in Spain is to fundamentally change.

Nudged into action by the EU and the Warsaw Convention of 2005, Spain made human trafficking a criminal offense for the first time in 2010. In 2015 this law was tightened further, and authorities adopted a collective approach whereby security forces, prosecutors, judges and NGOs would liaise to nail the trafficking rings together, a strategy reflected in a report by the Interior Ministry's Counter-Terrorism and Organized Crime Intelligence Center (CITCO), which has been accessed by EL PAÍS.

You think that one day, the ordeal will end, but the debt does not decrease, it just goes up

Katy, former prostitute

Now, a much clearer picture is emerging of the underworld that has been thriving under our noses for years. And the extent of it is nothing short of horrific – there were 4,430 victims of human trafficking and sexual exploitation identified between 2012 and 2016. This figure rises to 5,675 if we include those who have been forced into unpaid labor. In 2016 alone, 1,046 victims were rescued.

The figures are shocking, but far worse are the victim’s stories. These people tell of working off debts that never diminish, isolation, a lack of Spanish language skills and a level of fear and violence that keep them from seeking help.

In the town of Figueras in Catalonia, a trafficker’s sister made off with the baby of a Romanian woman who was forced to sell her body at a roundabout in La Junquera, a border town that thrives on sex tourism. Another victim had her three-year-old taken from her and sent to Ibiza, and she was only able to see her child on Skype – but only if she paid to do so.

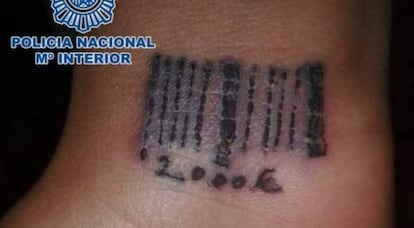

In 2012, a Romanian woman who escaped was recaptured, tied to a radiator, had her head shaved and a barcode and her debt tattooed on her wrist as an example to her fellow victims.

Nigerian women are often raped on their journey across the desert, which can take as along as a year. Those who get pregnant and give birth frequently have their babies taken from them. The women are scared to step out of line for fear that threats to their families will be acted upon. There have been cases when a victim’s family home was burned down, and her family members beaten and even murdered.

The most horrific cases of sexual slavery involve minors working in roadside clubs and apartments. “We are coming across more and more minors or women who were minors when they were first enslaved,” says Marta González, director of Proyecto Esperanza, one of the main NGOs involved in the rescue and rehabilitation of victims.

Unfortunately, these minors are often the hardest to help, as there are no specific centers to meet their needs; meanwhile, a lack of cohesive approach from the various regional governments of Spain has not facilitated an effective solution.

Passports as weapons

In the slave trade, passports are promptly confiscated by traffickers. Consequently, the victims are not only alone in a strange land where they do not speak the language, they also have no document to prove who they are.

"Those who fly in have it removed at the beginning of the trip and only get it back to go through police control at airports,” says a spokesperson for the security forces. “Once the victim is through, the passport is taken from them again. Often, when we enter a club, we find that one of the suspected traffickers has all the passports in a safe.”

Fraud is also part of this multi-million dollar business. “A good false document costs these networks between €5,000 and €6,000”, says a spokesperson for the Central Squad of the UCRIF for document forgery.

Naturally, the traffickers try to claw back some of their investment by recycling the documents. According to police sources, Bangkok is the Mecca for forged passports. When it comes to Africa, however, Nigeria is King while Chinese victims often arrive in Spain with a Japanese passport.

Equally vulnerable, if not more so, are victims with disabilities. Several months ago, the police rescued a mentally disabled woman from a brothel after infiltrating an internet forum used by men who had taken advantage of her and were mocking her online.

The definition of human trafficking, as set out in the 2000 UN Convention, is an act involving deception, a transfer to another country or place and exploitation that infringes on a person’s liberty. And while trafficking rings are overwhelmingly involved in sexual slavery, there are other forms of exploitation, including unpaid labor.

Spain is only just becoming aware of this other brand of slavery that often involves male victims made to work in agriculture, textile sweatshops, restaurants, kebab or wok establishments, domestic service or bars. Legally, this kind of slavery is harder to prosecute, but the authorities have begun to press charges in a number of cases.

In just two years, 534 people have been arrested. However, getting charges to stick has proven more difficult. “The law requires an overhaul to clarify certain concepts,” says Enrique López Villanueva, from Spain’s National Rapporteur on Human Trafficking. “It is very difficult to determine what is pure exploitation and what are simply subpar working conditions.”

In 2015, other forms of trafficking began to be investigated by the Crime Commission. Smaller in scale, they are even more difficult to define, and include enforced theft, enforced drug dealing, enforced begging, enforced marriage and enforced organ donation.

Of those enslaved in the sex trade, 96% are women. Most of them come from Romania, China and Nigeria after being duped by traffickers. The Romanian women are often tricked by a ‘lover boy’ – a young man who seduces them with the promise of a better life. When it comes to Nigerian women, voodoo is often part of the equation: the deal is sealed with a magic ritual performed in the victim’s village in which the trafficker keeps a small packet containing the victim’s pubic hair, bits of their nails or menstrual blood with their name on it. This gives him a hold over his victim that is hard to shake.

But it is not just people from Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe who are being tricked into slavery. At times, the Spaniards who have fallen victim to this practice have outnumbered the foreigners.

So why does nobody stop this? According to experts, business is business and there is a lack of political will to intervene. Spain has 1,700 brothels with a collective daily turnover of €5 million, not to mention the money generated from advertising.

“Trafficking cannot be separated from the final ‘job’ the victims find themselves forced into, so it depends on how that ‘job’ is regulated,” says Joaquín Sánchez Covisa, a prosecutor specializing in foreigner issues and an expert in the field. “If pimping goes unprosecuted, we create a haven for traffickers. You cannot effectively prosecute trafficking without making pimping illegal.”

The National Police and Civil Guard, along with the prosecutors, specialized judges and NGOs working with victims, agree on one thing: pimping should be banned and no one should be able to profit from another’s prostitution. But, currently in Spain, pimping is only an offense if it involves violence, coercion or abuse, scenarios which are almost impossible to prove if the victim does not report it. Investigations are complex, requiring international cooperation and sophisticated surveillance.

Changes to the law have helped reveal the extent of the phenomenon

When the penal code was reformed in 2015, there was a move to make pimping illegal, which would have entailed the closure of roadside clubs and banning of erotic advertising. The bill made it through Congress, but it was amended by the Popular Party in the Senate, which reworded it to leave it open to interpretation, thereby making it more challenging to prove the offense. And while the “vulnerability” of the victim is now one of the defining criteria, the term is too vague to make it effective.

Still, from 2012 to 2016, 3,000 people were arrested for trafficking and sexual exploitation and 277 criminal groups were dismantled.

“The problem is largely one of demand,” says Enrique López Villanueva. “And the problem will continue until it is tackled. I am not talking about prohibition or legalization. I am talking about regulating and legislating. Pimps take advantage of the legal vacuum.”

“If you close a club for trafficking, it reopens two days later and the customers are back,” says Maria Gavilán, a reserve judge in the Madrid region who belongs to the Association of Spanish Women Judges (AMJE) and specializes in this line of criminal activity.

A EU directive released in 2011 expressly states that member countries should consider measures to criminalize the use of services provided by the victims of trafficking, a move that would tackle the problem of sex tourism.

With so many traffickers feeding off the sex trade, it is hardly surprising that Spain is now a sex tourism destination. For example, clubs in La Jonquera, on the border with France, collectively amount to the largest brothel in Europe. “This,” says Villanueva, “is not something that is recognized, nor is it an easy topic to address.”

“According to the UN, Spain takes third place when it comes to demand for prostitutes, after Thailand and Puerto Rico. Demand is the key,” says Rocío Mora, Director of the NGO Apramp. She believes there are very few women who prostitute themselves voluntarily. “The vast majority are victims of trafficking or sexual exploitation,” she says.

The approach has improved. Prosecutors have received specific training with a view to tackling traffickers, and the police is cooperating successfully with NGOs working in the field. Last year, over 2,500 inspections were carried out at locations known for prostitution, 73% of which were in clubs. The specialization of professionals and a collective awareness are key to making a difference, because the trick is to be able to identify cases of trafficking when confronted with them.

As there is no longer an association representing the proprietors of brothels, it is hard to get their collective point of view on the subject, but EL PAÍS found an owner who was willing to speak.

If you close a club for trafficking, it reopens two days later and the customers are back

María Gavilán, specialized judge

“It might surprise you to know that I am actually in favor of banning pimping and prostitution,” said Alberto Martínez, who has been in the business for 20 years, own three clubs in Barcelona and has one opening in Madrid soon. “However, being realistic, it’s not about to disappear and so I think it should be regulated to avoid a legal vacuum that the mafias can exploit.”

In Catalonia, prostitution is partly regulated – clubs must have a license and be registered to encourage “clean and transparent” activity. "The sector’s image is very negative,” says Martínez. “That’s a fact, so I understand why we’re all tarred with the same brush.”

“It is absurd to consider any woman to be free who works 24 hours a day for a year and at the end of it has no bank account, no money, no property, no rent for the apartment she lives in and no right to refuse a client,” says Beatriz Sánchez, the prosecuting attorney who succeeded in sending Ioan Clamparu, the ‘capo’ of the biggest prostitution trafficking ring in Europe, to prison for 30 years in 2012. Sánchez believes the traffickers’ budget and strategies far exceed those of the authorities and that there are not enough resources invested in victim and witness protection. She also points out that there is a linguistic problem when victims or suspects speak in dialect.

But most of the time, it doesn’t take more than common sense to get to the truth. “Who’s going to believe that a Paraguayan woman who does not speak Spanish, only guaraní, is going to come to Spain because she wants to live in an apartment in Bilbao where she is locked up 24/7?” says another prosecutor.

We are coming across more and more minors or women who were minors when first enslaved Marta González, director of Proyecto Esperanza

This is one of the telltale signs that a woman or girl is being exploited by a prostitution ring. Others include being locked in clubs where they have all their meals. In the case of streetwalkers, they might have their food taken to them by ring members, as well as wood to make fires to keep warm. “There are women who are taken straight from the airport to Calle Montera in Madrid [famous for prostitution] and don’t even know what city they’re in,” says Rocío Mora from Apramp.

Apramp sends teams of women who have survived trafficking ordeals onto the streets to seek out victims to help. In 2016, they rescued 1,259 women who were then placed in rehabilitation programs.

Katy, the name used by a Brazilian survivor who now works for Apramp, says: “You think that one day, the ordeal will end, but the debt does not go down, it just goes up. I have made enough money to have a good life, but they steal it from you. You are alone –there is no such thing as friends in that world. Clients are rarely kind. They tell you, ‘I don’t want to hear your problems; if I wanted that, I would stay home with my wife.’ Hardly any women are in this through choice. The oldest profession in the world is not prostitution, it's looking the other way.”

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.