Accents make a comeback in California

Assembly is studying a bill that would allow diacritical marks on Spanish names in official registers

The address of most Californians is basically Spanish – though they write it in American-influenced Spanish. Cities such as Los Ángeles, Santa Mónica or San José are not written with an accent. In fact, it is against state law to use diacritical marks in public documents. The same thing happens with the names Ángela, Mónica and José. On official documents such as birth certificates, the accent must be omitted.

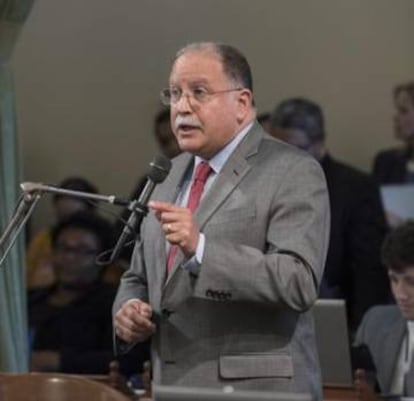

Jose Medina, a California assemblyman, recently introduced a bill aiming to overturn the ban on diacritical marks so that Spanish names can include accents and the distinctive letter ‘ñ’ in official documents.

“The State Registrar shall require the use of a diacritical mark on an English letter to be properly recorded, when applicable, on a certificate of live birth, fetal death, or death, and a marriage license,” says the bill. “The use of a diacritical mark on an English letter shall be deemed an acceptable entry on a certificate of live birth, fetal death, or death, and a marriage license by the State Registrar. For purposes of this section, a diacritical mark includes, but is not limited to, accents, tildes, graves, umlauts, and cedillas.”

The bill passed unanimously in its first round of voting by a California assembly committee with a Democrat majority. But even though it appears to have the support of both parties, the bill still needs to be voted on by the budget committee and at a plenary session. A similar bill introduced in 2014 did not get beyond this point after state agencies estimated it would cost $10 million to reprogram and upgrade their IT systems and searchable indexes.

Among the 25 most popular names for boys published by the US Social Security Administration, there are five which are common to both languages but normally take an accent in Spanish – namely Sebastian, Julian, Angel, Adrian and Aaron. The 39th most popular is the typically Spanish name José, which has fallen out of favor in recent years. In the female camp, the most popular name is Sophia, in its English spelling, while Sofia ranks seventh. More than 2,000 baby girls were registered as Sofia without an accent in California in 2015.

“A name is linked to a person’s identity, history and heritage,” said Medina during the first round of voting. “ This should be precisely reflected in important documents while parents should have the right to choose a name without government interference.”

The 39th most popular is the typically Spanish name José, which has fallen out of favor in recent years

Medina went on to point out that not all states omit diacritical marks in official documents. “As a state that is proud of its diversity and inclusion, I hope that California can grant this fundamental right to its citizens,” he said.

The bill does not refer to the Spanish accent alone, but to all diacritical marks that can be found on the average keyboard. As Medina says, we live in an era when technology allows us to write these names in a way that can be recognized by the computer equipment of official registers.

If the bill is approved, it will allow children to be registered with names that include the Catalan cedilla (ç), acute and grave accents (é or è), umlauts (ö or ü) and tildes (ñ or ã). Names such as Chloë o Zoë, Benoît o Eça will all be officially recognized with all their marks – which is surely good news for singer Beyoncé.

In 1986, a wide majority voted to make English the official language in California. And though the legislation has since been watered down, much of it remains in place with regard to vital documents. Thousands of Spanish names in California have been Americanized. But there are exceptions. For example, in Beverly Hills there is a street that is called Canon Drive in one part and Cañon Drive in another. Expecting them to spell it Cañón with an accent was just too much.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.