The danger of speaking Spanish in the United States

The use of this language, spoken by 40 million people, continues to grow. It is doubtful that President Trump will manage to reverse this trend

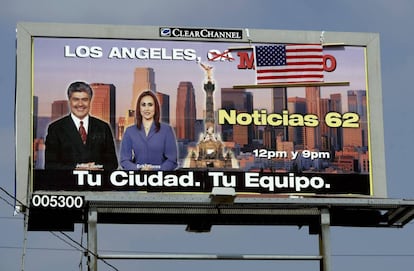

In the United States, 57 million people consider themselves Latino and 40 million speak Spanish, out of a total population of around 308 million. These facts highlight a historical constant: the ability of the Spanish language to resist an institutional environment that has been, and is currently acting, hostile. Laws attempting to eradicate bilingual education have systematically failed, because the use of a language depends on the people who speak it, and not on legislation.

Data support faith in the vitality of Spanish in the United States, from its use in homes and communities, to its presence in the media, especially on television. Spanish also has considerable weight in American academia. Despite the fact that US President Donald Trump added an official Twitter account in Spanish, what does the news about the deletion of Spanish from the White House’s website mean?

To deny the importance of Spanish in the United States is as insane as denying climate change

In a video from 1960, which today seems rather poignant, Jacqueline Kennedy speaks Spanish, asking Latinos to vote for her husband John F. Kennedy, who at the time was a senator. This was not an isolated case. Throughout the more than half-a-century since then, the Spanish language has been used with certain regularity in the presidential milieu, by both Republicans and Democrats. Everyone remembers George W. Bush’s attempt to engage with Spanish. Meanwhile, his successor, Barack Obama, thought it important that the official White House webpage do justice to the bilingual reality of the United States, integrating Spanish into its design. Spanish is not the only thing that has disappeared from the White House’s webpage: also deleted are allusions to Cuba, climate change and the Iran nuclear deal, among other things.

To deny the importance of Spanish in the United States is as insane as denying climate change – something that, incidentally, the new administration is doing with complete impunity. The historical, social, political, economic and cultural weight of Spanish in the United States is an unquestionable fact; the problem is that facts do not matter when it comes to a political agenda where reality is denied on a systematic basis.

In terms of the demographic force of the Latino community in the United States, Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez solemnly summed it up when he said: “It was not us who came to the United States. It was the United States who came to us.” And how did they do it? Through a simple operation of buying and selling. In 1848, after a military conflict, Mexico ceded half its territory to its northern neighbor for $15 million under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Overnight, a huge part of the Spanish-speaking population became part of the northern territory. A survey of place names serves as a silent witness to the trampling of this territory by the United States. Names such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Nevada, Colorado, among many others, each have their own history. If geography is unequivocal, the same cannot be said about history, which Anglo-Americans have always told badly, prioritizing the vision of an expansive horizontal movement from coast to coast; heading west.

Despite what is usually argued through imprecise statistics, the use of Spanish does not decrease from one generation to another in a lineal way

The Hispanic vision, centered on an examination of a vertical South-North axis, has been emphasized by researchers such as Professor Fernández Armesto in Our America (the title, as is well known, comes from Cuban national hero José Martí), but it is systematically ignored.

More data. California, which sometimes flirts with the dream of independence, is, besides being the richest state in the country, a pre-eminently Spanish-speaking territory. In Miami one can get by without speaking any English at all. Another fact worth underlining is that, despite what is usually argued through imprecise statistics, the use of Spanish does not decrease from one generation to another in a lineal way, given that the constant flow of new immigrants counteracts any such fall. Other languages such as Yiddish, over extended periods of time in places like New York, have disappeared without a trace: Spanish, in contrast, has not stopped growing, a trend that the new administration seems determined to halt. The ever-changing history of relations between Spanish-speakers in the US and their maternal language switched from being defined by an inferiority complex to a phase of assertion and pride. But now there is an additional element: fear. Speaking Spanish in public could be dangerous in the face of the threat of a massive wave of deportations.

Eduardo Lago is a writer and the former head of the Cervantes Institute in New York.

English version by Alyssa McMurtry.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.