With 135,000 murders a year, crime is Latin America’s top concern

Security gathering in Buenos Aires estimates the cost of escalating violence at $120bn a year

Security is a major political issue in practically all of Latin America.

In Peru, it was at the center of a presidential campaign that nearly handed victory to Keiko Fujimori, because of her hard stance on crime and violence. In Venezuela, Mexico, Brazil and even less-violent nations such as Argentina, it is citizens’ chief concern.

The figures help to explain why. Nearly 135,000 people were murdered in 2015 in Latin America and the Caribbean, representing a homicide rate that is four times the global average, according to the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

In Argentina, the government has decided to station more officers at the borders to prevent drug smuggling

This international organization estimates the annual cost of crime and violence in the region at $120 billion, or around $200 per person. Latin America could raise its per capita GDP by 25% if it could only bring its crime rate down to levels found elsewhere in the world.

The IDB is organizing a Security Week in Buenos Aires “to promote more dialogue and knowledge exchange on crime and violence,” and to reorganize national police forces more effectively.

Insecurity and inequality

Latin American countries may be very diverse, but there are two elements that they share: insecurity and inequality. In recent years, enormous economic growth derived from a boom in raw materials and a redistribution of wealth by left-wing governments have managed to reduce poverty. Education and public health have also improved noticeably.

Yet crime and violence rates have not decreased. In fact, even nations that were doing better than average on this front, such as Argentina, are now regressing.

“For the last 10 years we’ve been systematically doing worse,” explains Eugenio Burzaco, the number two official at Argentina’s Interior Ministry. “Our country has lower levels than other countries in the region, but compared with ourselves, we are doing worse. We have a rate of six homicides for every 100,000 inhabitants, which is low for the region, but twice what it was 20 years ago. And violent crimes without homicide are increasing dramatically.”

Meanwhile, Honduras has a homicide rate of 84 murders for every 100,000 people (the figures are from 2013); in Venezuela it is 53, in Colombia 31, in Brazil 28 and in Mexico 19. Chile is at the bottom of the list, with just three homicides per 100,000 people.

This deteriorating security situation is holding back the region economically, and forcing many people to flee to Europe or the United States. The IDB estimates that the region spends around $51 billion a year on its police forces.

“Latin America has an average of 23 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. That is twice as much as Africa and five times as much as Asia. One out of every five Latin Americans view this as their biggest problem,” says José Luis Lupo, manager of the Southern Cone Country Department at IDB.

One out of every five Latin Americans view this as their biggest problem

José Luis Lupo, IDB chief of Southern Cone Department

Natalie Alvarado, who coordinates the IDB’s security area, admits that regional statistics are insufficient but still useful to find patterns.

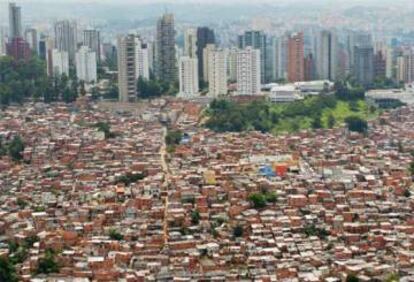

“Southern countries are very worried because there has been a rise in victimization – the number of people who report having been victims of a crime. The region has grown a lot, but security is not improving,” she notes. “There is an enormous population of youths who are neither in school nor holding a job, and a great institutional vacuum. Penitentiary systems are in crisis because they are crime centers where, far from rehabilitating, criminals hone their techniques. Disorganized urban growth in Latin America’s major cities is the ideal breeding ground.”

Better, not more

All experts agree that the key lies in reforming law enforcement agencies, rather than increasing the number of police officers on duty.

“Honduras, which is in a very delicate situation, is focusing its reform on police recruitment and training. There is evidence in every country that more police does not equal more security,” says Alvarado. “Ecuador has also made progress. Before this, police officers were people who had no other career options, who had no future. We need to dignify the police.”

Yet citizens seem to be asking for more patrols on the streets. In Argentina, the government has decided to station more officers at the borders to prevent the drug smuggling that is at the origin of much of the nation’s security problem. People want to see uniformed officers near their homes in the cities.

Nobody has a definitive solution, but everyone agrees that security is Latin America’s great 21st-century problem, and that it affects the poor more intensely because they cannot afford to hire private bodyguards.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.