Inequality drags back Colombian growth

As the economy rises 4.7% a year, the gap between rich and poor remains one of world’s largest Inadequate education and a sizeable informal economy are the main factors

Germán Gómez runs a simple business. He sells cellphone minutes to people walking along a busy commercial street in Bogotá, in a financial district filled with shopping centers and cafés. Every day he sets up his cart, his parasol and his sign bearing the words “By the minute, all carriers.”

A young woman stops in front of his stand; he pulls out an old cellphone and dials the number. After her conversation is over, he charges her.

“A lot of people use up their prepaid cards before the end of the month, and they come here to pay by the minute,” explains Gómez, 62. “I buy a lot of them, that is why I get them for 110 pesos and charge 200.”

Standing next to him is Julián Abril, a 27-year-old driver who works for an engineering company. He studied engineering himself for two years, but had to drop out when he could no longer afford the tuition fees.

Neither man has the impression that they live in a country whose economy has grown at an annual average rate of 4.7 percent in the last four years, where foreign direct investment grew eight percent in 2013 from a year earlier to reach nearly $16.8 billion, and where inflation is a mere 2.3 percent. Even unemployment, which was 9.6 percent last year, is going down.

We don’t have the education we need for the economy we want”

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has just praised the macroeconomic orthodoxy of Latin America’s fourth largest economy, a place where the middle class has grown to 27 percent (still low compared with Chile or Mexico) and where, as President Juan Manuel Santos likes to point out, 2.5 million people have been lifted out of poverty in the last four years.

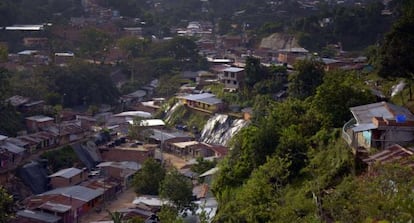

But while all this is happening, one thing has barely changed at all: inequality. In Colombia, the gap between rich and poor is among the biggest in Latin America and in the world.

Juliana Londoño, a Colombian PhD student at Berkeley University in California, has put numbers to this phenomenon: the wealthiest one percent own 20 percent of total wealth.

“That is one of the highest concentrations, as high as in the United States,” she explains. Londoño’s findings on Colombia were included in a book that has recently shaken up the public and scholarly debate, Capital in the 21st Century, by the French economist Thomas Piketty.

One of the reasons for this figure is the structure of the labor market. Gómez and Abril work in the informal economy; half of all jobs created in Colombia are of the same nature. This produces a huge difference in job quality and income, compared with regular employment and its access to social security and retirement checks.

The other great generator of inequality is education, which rather than helping people climb the social ladder, “perpetuates the inequality,” says Londoño. “Good quality higher education is concentrated in a very select group with the highest income.”

Before the campaign for the presidential elections turned into a slanging match between the incumbent Santos and opposition leader Óscar Iván Zuluaga over drug money and spying scandals, education was a major issue under debate.

The wealthiest one percent own 20 percent of total wealth in Colombia

Three days before the first round of the elections, the online news portal Kienyke asked four out of the five contenders whether they ever hesitated over sending their children to public or private schools. All four presidential nominees have degrees from prestigious universities: Duke (Enrique Peñalosa), London School of Economics (Santos), Exeter (Zuluaga) and Harvard (Marta Lucía Ramírez). All of them admitted it was never a question for them.

“We don’t have the education we need for the economy we want,” concludes Isabel Londoño, an advisor on education policies.

Julián Abril worked as a clerk at a car wash for a while to pay his way through college. “I had to go to a private university because I was not admitted into a public one,” he says. It is hard to get admitted into a public university in Colombia: there are few spots, and students coming from public high schools are not as well prepared.

Samuel Freije, the chief economist for Colombia at the World Bank, believes that inequality persists because of the enormous gap between the cities and the countryside (where poverty and war strike the hardest). But it also has to do with education, he says.

“Modern life requires more university graduates, and there are growing numbers of young people demanding access to university. We need more resources and a greater offer for the less wealthy,” he says.

Freije nevertheless underscores the rise of the middle classes over the last decade. “In 2002 it was 15 percent of the population, and now it is 27 percent, and this middle class wants more education and more public services.”

Several experts agreed that the government has made an effort to redistribute the wealth through various social programs.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.