Skilled Spaniards seek Uncle Sam

Experts say that where Spanish emigrants used to look to Europe for new opportunities, they are now heading to the US in search of the upward mobility they cannot find at home

The economic crisis has triggered a Spanish exodus. Highly qualified workers, faced with a jobless rate of more than 20 percent, have been trickling to the west, their eyes set mainly on the United States, where they feel they have a better chance of finding a job.

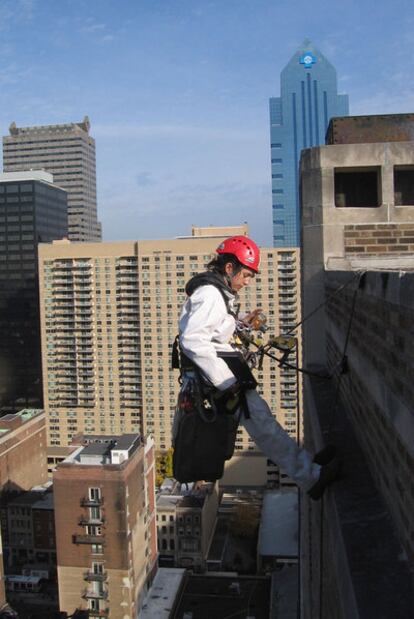

Engineers, doctorate students, an enologist who spends half the year in California and the other half in Australia, an architect who rappels down Manhattan's skyscrapers on a daily basis, an engineer who works at Miami's major building sites and the medical director of a Boston hospital's emergency unit are just some examples of Spaniards who fulfilled their career goals nearly 6,000 kilometers from their homeland.

"In Spain it is hard to get a decent job based on your own merit. It is a country where string-pulling is what works best," says Germán de Patricio, 43, who went to the US in 1996 to get a master's degree. He returned to Spain, where all he could find was a job as a substitute high school teacher, and he ended up moving back to the US. After obtaining a PhD in literature from Virginia University, he now teaches at Towson University in Baltimore. "I feel appreciated here, I see that I have a professional future and great opportunities for improvement," he explains. "If you have the desire to work, you have the option of moving up. Spain doesn't work that way."

A 2010 US census showed over 635,000 Spaniards were living in the States

"If you want to work, you can move up. Spain doesn't work that way"

Germán is in the US on a H-1 visa, typically granted to people who have completed their PhD studies. He hopes to apply for permanent residency in the coming years, although that document may cost him around 6,000 euros. Each year, the US government hands out around 140,000 green cards (residency permits). Each country, whether India or Belgium, gets seven percent of those green cards at the most. But the law was changed in December to extend that limit to 15 percent with a view to the needs of the US labor market. This has benefited countries with the greatest demand for visas such as China and Mexico, and harmed smaller countries such as Spain.

Out of all these visas, 55,000 can be won through an annual lottery run by the State Department. Nine million people participated in 2007 and by 2012 that figure had ballooned to 19.6 million. In 2007, when there was still no talk of crisis in Spain, 6,909 Spaniards applied for the green card lottery. In the latest one, there were 15,362 Spanish applications.

There is a reason why they call it a lottery, and Israel Nava, 32, certainly feels like a lottery winner. "I didn't know what to do this year, considering the way things are going in my sector in Spain," says this audiovisual technician, who specializes in film post-production and also works in television. Last April, he was informed that he was one of the green card winners. So far he has spent around 1,100 euros in sworn translations, medical reports, embassy fees and other kinds of paperwork. In March, he will travel to Kentucky to get his green card, and then he wants to move either to Los Angeles or New York.

"I am anxious to see what my industry is really like," he says. "I've been working in this sector for 12 years, and the last two have been especially bad, because we are so dependent on grants and public money. I get the feeling that the industry works differently in the US, that it is not as precarious as it is here. That is what I'm seeing lately in Spain: a lot of odd jobs and a lot of job insecurity."

Eusebio Mujal-León, a professor of politics at Georgetown University in Washington, has noticed the trickle of Spaniards over the last few years. "These are people with a great future who come looking for an opportunity, who try to prolong their stay once they graduate and who join the US labor market while they wait for the crisis to pass," he says. "Once they're here, they do not hesitate to stay."

In the last US census of 2010, citizens had the option of identifying themselves as Hispanics and specifying whether they were Mexican, Puerto Rican or "other." Under the "other" category, people were asked to put down their origin, suggesting things like Argentinean, Colombian, Dominican, Nicaraguan, Salvadoran or Spanish. In total, 635,253 people described themselves as Spanish.

But the figures offered by the Spanish National Statistics Institute are notably different. The national census holds that there are 1,702,778 Spaniards living abroad, of which only 74,495 live in the US. The figure was updated in January of last year, and it showed a considerable increase since 2008, when there were 66,979 Spaniards living in the US, representing an 11 percent rise.

According to sources at the US Embassy in Spain, the discrepancy in the numbers could be due to confusion among US citizens regarding the term "Spanish."

"It is possible that lots of people got it confused with the fact that their ancestors were of Hispanic origin," said an embassy source. Also, the figure of 74,495 offered by the Spanish government does not reflect all Spanish residents in the US. "Some come on a temporary basis as exchange students and they do not register with the consulate. But that is a very reduced number."

Mujal-León underscores that the main ways into the US are fellowships and PhD studies. Lucía Rodríguez, 28, takes 28 hours to get from Tucson (Arizona) to her family's home in Galicia, but this PhD student in environmental engineering did not hesitate to go when she got the chance. "They were offering me all sorts of things here. The situation was bad, I was offered a grant, and I knew I had no other options. The way things work right now, leaving is your one opportunity; you have to be open to new things and be willing to travel."

"It makes no sense for us to have a public education system so that wealthier countries can later benefit from it with such an export of talent," says Ayatima Hernández, 33, a consultant at an international agency in Washington DC. Since 2008, she has also looked back and lamented the fact that Spain does not appreciate the effort of its professionals, who are often forced to emigrate.

By the time Patricia Casbas, 27, began her last year as a biochemistry student, she was already considering leaving Spain afterwards. She eventually landed in Chapel Hill (North Carolina), and by the following year she had joined a PhD program that conducts breast cancer research, all expenses paid. "I've been here since August 2007. The opportunities that the US has given me, I unfortunately never did and never will get from Spain. That is why I came, and that is why I stayed."

Another way in is through study grants like the Fulbright fellowship, which has sent over 4,700 Spanish students to US universities in over half a century. In recent years, there has been a considerable rise in applications. In 2008, around 310 candidates applied for programs in higher education, artistic studies and foreign language teaching. In 2011, that figure had almost doubled to 556 candidates.

The committee that runs these scholarships is tasked with providing academic advice, covering transportation and living costs and paying the tuition fees. Its funding comes chiefly from the Spanish government, although the US government also contributes some funds. Students travel to the US on a J-1 visa, which requires graduates to return to the European Union for two years before applying for a work permit in the US.

"We are interested in responsible professionals who are aware that they are, to a certain extent, morally indebted to the society that helped train them, and who are willing to work for the benefit of said society," explains Alberto López San Miguel, the new committee director. "It's true we have noticed a rise in applications in recent years, no doubt because the crisis is forcing youngsters to seek new alternatives, and perhaps there are people applying for scholarships who would otherwise choose different avenues for their personal and professional growth."

Mujal-León lists several reasons for so many Spaniards to be going abroad: the high unemployment rate, the state's problems in creating jobs, demographic characteristics - a large proportion of pensioners compared with the active population - and the considerable hurdles for entrepreneurial initiatives, which could be a source of job creation.

"If a few years ago, young people viewed Europe as the top destination to improve their English or expand their professional options, now they look to the United States instead," he says. "Despite the economic recession, this country has never stopped demanding highly qualified professionals, especially in certain specific fields."

Some Spaniards go off in search of opportunities in one of the greatest business hotspots in the world: Silicon Valley, the epicenter of technological innovation. Miguel A. Díez Ferreira, 40, arrived in San Francisco in August looking to expand his business, Red Karaoke, which commercializes mobile applications for singing over the telephone. He came here with his wife, and both have already met representatives from Apple, Facebook and Google, among others.

"People in the US are more accessible when it comes to doing business," he says. "Gaining access to most people is simple, you can talk to just about anyone if you have a good product or an interesting proposal for them. In the US, you work fewer hours, but the hours you put in are better quality: people really focus and get the most out of every minute, they are much more productive than in Spain."

Bruno Llorente, 35, is a resident of Santa Monica who has also seen these differences. After working for six years at a telecom multinational back home and watching the job market progressively deteriorate, he took the risk and moved to the US. "I left just when the worst was about to hit," he recalls. But his is a different kind of problem now. "The hard part is not getting out, it's getting back in. There are a lot of people like me who want to go back home, but we can't."

"I would love to go back," adds José Luis Cuesta, 28, who works for Discovery Communications in Miami. "But not to this Spain; to a different Spain where work gets the credit it deserves, not what it gets now."

Cuesta's case is special: his father is Spanish and his mother is American, and because he has dual citizenship it was easy for him to move to the US where his two siblings were already living. "When that day arrives, I will consider returning to the culture that I belong to, but for now I need to be pragmatic and cool-headed, and keep a lid on the anger I feel at having had to leave out the back door."

Cuesta left Spain because of job concerns. He also left behind a newly bought home, his wife, and unless they find a way of being reunited soon, the baby that they are expecting.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.