Shock tactics

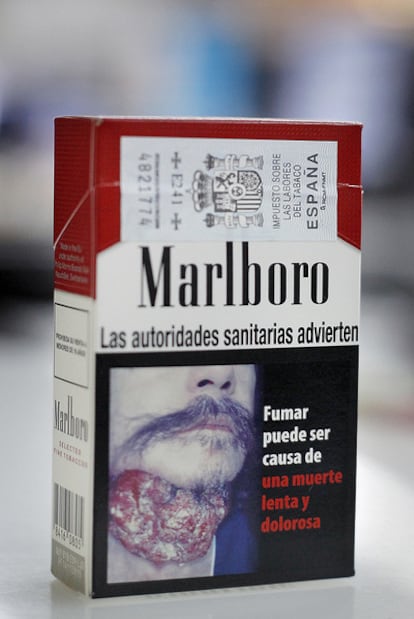

The government's latest weapon in the fight against smoking is the inclusion of images of tumors on cigarette packets. Critics argue they show a lack of respect

An eaten-away jaw, rotting lungs, a throat tumor and open-heart surgery. These are just a few of the photographs to be found on around 40 percent of cigarette packets. In a bid to further heighten smokers' awareness of the danger their habit poses to them, the World Health Organization has forced tobacco companies to publish 14 different graphic images of illnesses associated with smoking on packets. But the shock tactics have prompted complaints questioning whether there is any need to be so explicit in proving something that we all know already: that smoking is bad for your health.

Toward the end of May, a reader from the Galician port city of Vigo wrote to EL PAÍS to express her anger at the use of the images. "They are a flagrant act of aggression against the sensibilities of the person who comes into contact with them. Aside from the unnecessarily graphic depictions, they are an insult to the intelligence of all of us, and to smokers in particular. Smoking may kill, and is not good for the health, but there is no way that this fact gives anybody, neither our mentors nor governmental gurus, the right to underestimate our intelligence and to treat us as though we were soft in the head."

Media experts say that the "ends justify the means" approach doesn't work

"They have crossed the line here in terms of decency, especially for cancer victims"

"This is typical of the government - they know nothing about communication"

"For some smokers, it has an effect, and for others, it simply makes them think"

Response to the campaign runs from one extreme to another: health experts say it is the best way to address the problem, while experts in mass media say that the "ends justify the means" approach to getting the just-under-a-third of the population who smokes to stop just doesn't work. "It is worth asking whether the state has the right to behave in this way," says Xavier Oliver, an advertising expert, and teacher at the IESE business school. He argues that the images go too far. "They have crossed the line here in terms of decency and respect, especially regarding cancer sufferers. They may seem to have an impact, but this is not a serious approach to communication. Make people think, but don't treat them as if they were brainless."

Rodrigo Córdoba, a doctor and member of the National Committee for the Prevention of Tobacco Use, says that the reality of smoking is tougher than the images suggest. He reels off figures and statistics, reinforcing his argument with the personal story of a friend who recently died of cancer of the larynx. "We see these tumors all the time, not just on cigarette packets," he says.

Health Ministry figures show that smoking is the number-one cause of avoidable deaths in Spain, with some 60,000 people dying from smoking-related illnesses, 1,500 of them passive smokers.

Applying the utilitarian principle of the greater good, our governments have gone to increasing lengths to inform us about the dangers of smoking. Córdoba, author of 50 mitos del tabaco (or, 50 myths about tobacco), agrees with the use of the images. "If the messages were low key, they wouldn't have much impact, and nor would they be honest. Sadly, the effects on the body of smoking are bad, very bad. I understand that young people find it hard to identify with health messages, harsh or otherwise, and what's more it is not possible to employ the same message for all users, whatever their age - in the same way that you cannot have cars that only 25-year-olds are allowed to buy."

In 2003, the European Union, applying World Health Organization recommendations, approved a catalogue of 42 images, most of them very graphic, related to the negative consequences of smoking. The WHO's argument was that people needed to see the effects of the habit. "Messages and warnings on cigarette packets reduce the number of children who begin to smoke and help smokers who want to quit do so," said the EU.

In May 2010, Spain passed tough anti-smoking legislation, including a law obliging the inclusion of images of the effects of tobacco. But the images didn't arrive, it seems, until a few months ago. Spain was following the example of 10 other EU countries, among them Belgium (the first), France and the United Kingdom. The Spanish catalogue consisted of 14 of the 42 images, although the experts say that new images will have to be used over time if the campaign is to be effective. They say that people get used to seeing the same images.

Above and beyond the controversy, the latest Eurobarometer poll on tobacco use, published last year and based on 2009 data, shows that 75 percent of Europeans approve of the use of the images - in the case of Spain the figure is 77 percent. Not that the figures are any guarantee that they will reduce the number of smokers. Furthermore, the EU survey shows that the number of smokers had slightly increased since 2006 - when Spain's first major anti-smoking legislation was introduced, but largely ignored - from 34 percent of the population to 35 percent.

In September 2003, the EU's then-health and consumer-protection commissioner, Britain's David Byrne, said he was convinced that "an image really is worth more than a thousand words," and called for "innovative ways to illustrate the reality that half of smokers will die from illnesses related to their addiction." He argued that countries that were already using the images "had shown that this was an effective way to warn people."

Eight years on, Byrne's call for innovation seems to have gone unheeded, say the advertising experts. They claim that the images don't work aesthetically, and that they are overly gory. "This is the typical government response: they know nothing about communication. Showing death, blood - there is nothing innovative about that; it might get people to drive slower, but to change their attitudes? The most effective law, way beyond advertising campaigns, has been to ban people from smoking in enclosed spaces," argues Oliver.

"People feel as if they are under attack. This could prompt a rejection of the message, not the product," warns Carlos Rubio, the director general of the Spanish Association of Advertising Agencies (AEAP). There is little agreement on the effectiveness of the visual impact of say, a drooping cigarette as a warning that smoking can lead to impotence, or at the other extreme, a photograph of a body laid out in a morgue.

"From an advertising executive's perspective, it is terrible, but from a public-health angle, it is very effective," says Esteve Fernández, the head of the tobacco-control unit at the Catalan Oncological Institute (ICO), adding that there are two types of message: "The text, that smoking can kill, and the images. It has been proven that the message is more effective with images."

Along similar lines, Rodrigo Córdoba says there is conclusive evidence that the campaign worked in the first two countries to try it: Canada and Brazil. In his book aiming to dispel tobacco myths, he says that in Canada, 91 percent of smokers had read the warnings and visualized the images. "Reading the message is associated with an increase in the intention to quit smoking by between 11 percent and 16 percent. Some 23 percent try, and 24.3 percent manage to reduce the amount they smoke, while 10.8 percent quit altogether after three months' treatment," he says.

In the case of Brazil, 76 percent of people support the use of the images, and 54 percent changed their mind about the effects of smoking, with 67 percent saying that seeing the images made them want to stop smoking.

The advertising experts say that the effect of the images is short term. "Experience has shown that these types of campaigns are very effective in the short term. More than the inclusion of a photograph of a tumor, or a destroyed lung, what really matters here is the discussion and debate that takes place as a result of the campaign. For the first few days, the photos will be talked about, but then people stop looking at them," says Juan Carlos Martínez, head of the Lola advertising agency.

Esteve Fernández accepts that in some cases, the impact of images can be short lived. "For some smokers, it has an effect, and on others it simply makes them think, but the more images are used to explain that they shouldn't smoke, the better," he says. But he also accepts that the use of images should be backed up with other measures to reduce tobacco consumption. The WHO says that the images are part of a six-pronged approach that includes controlling consumption, protecting the wider population from smoke, offering help to smokers who want to quit, enforcing the ban on advertising and sponsorship, and increasing taxes on tobacco.

From a communication perspective, Xavier Oliver says it is important to raise awareness. "If this were the first part of a campaign to warn people about smoking, it would work. But this is not new. If you want to change people's attitudes about abuse, it has to be tough. But this is not the case here. This is simply in poor taste. It is making smokers feel as though they were committing a capital crime. This has to be done in two stages: firstly, to increase awareness about the dangers, and then to get people to really think about what they are doing."

Juan Carlos Martínez highlights the longer-term goals of the campaign: "When it comes to trying to introduce cultural changes, images have less worth than words. It isn't about making people aware, it is about getting them to do something," he says, drawing an analogy with road-traffic campaigns, which have shifted from the gory and explicit nature of the late 1990s to more sophisticated messages.

A habit is not the same as an addiction. And nobody is ruling out a return to the shock-value road-safety advertisements of a decade ago either. "I would like to see more campaigns that offer answers. We know what the problem is. It is better to see the positive side of things rather than getting mired in the problem. If you address these kind of issues with subtlety, you stand a better chance of achieving something," says Martínez.

This seems to be what has happened in Canada, where people simply buy cigarette cases to avoid having to see the graphic images of tumors. But every packet of cigarettes now comes with a small sheet of paper explaining in detail the dangers of smoking, and more importantly, advice on how to go about quitting.

The long march

- More than one billion people from some 20 countries are currently protected by laws that require cigarette packets to carry graphic images.

- Two years ago, that figure was at 547 million, according to the World Health Organization, which has been working hard to try and persuade more and more countries to join the initiative.

- Canada and Brazil were the first two countries to begin publishing photographs of the associated health risks of smoking on packets of cigarettes. Surveys show that the initiative is working, and that more people are giving up tobacco as a result.

- The European Commission gave the green light to the use of images on cigarette packets in 2003. The then-health minister, Ana Pastor, of the Popular Party, supported the move, but it was not passed until the following year, when the Socialist Party was in power.

- Spain is the 11th country to adopt the use of images, following Belgium, France, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Norway, Poland, Romania, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

- The law was introduced in May, although some packets already carried the images. The tobacco industry has been given two years to fully adapt its packaging to the new measures.

- Some 77 percent of Spaniards approve of the measure, according to the latest Eurobarometer survey.

- The Spanish Health Ministry says the main cause of avoidable deaths in the country is smoking. Each year, some 60,000 people die from smoking-related illnesses, 1,500 of whom are passive smokers.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.