AI swings between market euphoria and the specter of a bubble

Nvidia’s experience illustrates the investor’s fear of missing the great new technological wave ridden by big tech firms such as Apple, Microsoft and Alphabet

The bets on artificial intelligence (AI) have been driving the markets in the first half of 2024. Major technology companies and investors do not want to be left behind in a technological race that some compare to the advent of the internet or even the steam engine. But the current winner of this feverish dash is Nvidia, a company specialized in manufacturing the chips needed to train AI systems.

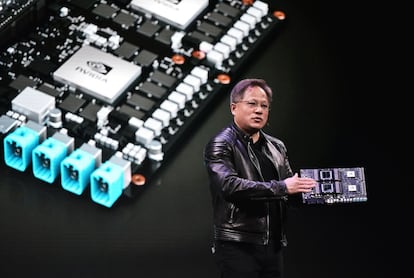

Headed by Jesen Huang and founded 33 years ago, Nvidia has broken more than a few records: it has led the S&P 500 in the last 12 months by tripling its value, and has become the most valuable company in the world, beating Microsoft or Apple, exceeding $3.2 trillion. Since the first ChatGPT model was launched at the end of November 2022 — the trigger for the current AI fever — Nvidia’s value has soared by 700%.

But it’s not just Nvidia that is rocketing in value. The big tech companies are going ahead full throttle to train their own AI models, and they’re getting the stock market’s blessing as they do so. Microsoft is up 38% in the last 12 months, while Alphabet — Google’s parent company — has climbed 57%. The phenomenon, however, has not been exclusive to the U.S. The European stock exchanges boast their own Nvidia equivalent: the Dutch giant ASML, manufacturer of the machinery on which microchips are printed, has been crowned the most important company in European markets after overtaking France’s LVMH. And in Asia, Taiwan’s TSMC aspires to join the club of companies valued at $1 trillion, after leaping 170% on the stock market in the first half of 2024, approaching a capitalization of $950 billion.

Investors have backed a technology that, without being new, is creating language and images, and whose development promises to revolutionize everything from the pharmaceutical sector by speeding up the creation of medicines to advertising thanks to hyper-personalization, to technology and computer programming to the oil industry. However, as the big tech companies break capitalization records week after week, the market is also expressing doubts: will this technology ever crystallize into corporate profits, or is the great AI rally a new version of the dotcom bubble of the 2000s?

In that era, the emergence of the internet and the proliferation of websites seemed destined to revolutionize everything. Although they did, the timing of the economy is not the timing of the markets. Consequently, before the great transformation, technology stocks plunged and thousands of projects, including some big ones, struggled to survive. A well-remembered example is that of Cisco, a manufacturer of equipment for deploying and connecting the internet, heavily favored — like Nvidia — by massive third-party investments. Cisco shares went from $5 in 1997 to $77 in 2000 to just $13 in 2002. They are now at $46.

New Street Research analyst Pierre Ferragu downgraded predictions on Nvidia’s value on Friday, July 5, arguing that its share price has already peaked. “A further increase will only materialize in a bullish scenario, where the outlook beyond 2025 materially increases, and we are not yet convinced that such a scenario will unfold,” he tells Bloomberg. But optimism seems to prevail. Nearly 90% of analysts tracked by Bloomberg recommend buying shares. “The results will take time, but they will come,” explains Flavio Muñoz, head of technology investment at Andromeda Capital. He believes it is unlikely that 2024 will see this technology reaching its full potential and delivering the long-awaited returns.

Companies are currently rushing their orders for specialized chips to ensure they’re on the transformation train, and their main supplier is Nvidia. Based in Santa Clara, California, the company first established itself as a leading manufacturer of graphics cards (GPUs) for video games. Over the years, these chips proved to be the most efficient for the type of work required to train neural networks, the core of AI, thanks to the fact they can perform multiple operations in parallel unlike normal processors, known as CPUs. The company had unwittingly turned into the golden goose. Since then, Nvidia has been perfecting its products with AI in mind, and orders have skyrocketed. In the first quarter of the year, the company’s turnover soared by 262%, after sales of $26,044 million. And profits rose from $2,043 million to $14,881 million, an increase of 628%.

The buyers fueling the feverish demand are members of the Magnificent Seven club — Microsoft, Apple and Amazon — who need the processing power of Nvidia’s GPUs to develop and run their AI models on huge amounts of data. This explosive demand is the basis of Nvidia’s stock market stardom. However, big tech has not been the only sector to board the gravy train. AMD, which also designs graphics cards, grew by 18% so far this year, and Qualcomm, which manufactures chips for cell phones, by 45%. Taiwan’s TSMC, which leads the way in semiconductor manufacturing, has also managed to post a 70% rise on the stock market while, in Europe, ASML has soared by 50% this year, to date.

Danny Fish, technology portfolio manager for Janus Henderson, says the existence of the internet giants is vital for AI technology to continue to develop. “They are the only companies that have the financial capacity and infrastructure to deploy the potential of artificial intelligence,” he says. UBS analysts pigeonhole Nvidia and its competitors in what they call the AI facilitation phase, which ranges from semiconductor design to chip design. “Investing in companies in this phase is recommended,” says the Swiss bank’s investment team, arguing that “while there is a risk that overcapacity fears could lead to volatility, the segment currently offers the best scope for reinvestment and reasonable valuations.”

The other two phases in the AI value chain, according to these experts, are intelligence and application. These phases are commandeered by companies that develop AI models such as Open AI (the second phase) and those that develop AI for specific sectors such as cybersecurity and financial technology (the third phase). At present, UBS believes that it is safer to bet on the first part of the chain, that of facilitation, because it offers “a strong competitive positioning, better reinvestment margin and reasonable valuations.”

Muñoz, from Andromeda Capital, points out, however, that it is necessary to look at other stocks participating in this ecosystem that have great growth potential. These include memory manufacturers for the operation of data centers, such as South Korea’s SK Hynix and U.S.-based Micron Technology; network infrastructure providers such as Broadcom and Cisco, as well as software firms and cybersecurity system providers such as Confluent and Snowflake.

Storm on the horizon

There are other managers, such as David Azcona, chief economist at Beka Finance, who warn that walls can still be erected to slow down the growth of the entire sector. The lack of concrete investments promised during the first part of the year and the emergence of competitors are the main risks, he points out. Matthew Bullock, chief strategy officer at Janus Henderson, adds that AI in its truest form is a fairly small market and there are very few companies that generate the largest slice of their revenue from it.

In fact, the Magnificent Seven alone have accounted for 60% of the S&P 500′s total returns this year. On average, S&P 500 stocks are up 4.1% this year, while the overall index has climbed 14.5%. According to The Wall Street Journal, this imbalance constitutes the largest since at least 1900. Muñoz explains that many investors are waiting for the next move by the U.S. Federal Reserve, which until last year was capable of making up to three rate cuts, “but now looks like it is not going to make even one.”

Azcona believes that growth will be moderate in the second half of 2024. The political uncertainty in the U.S. with elections looming and a scenario of diffuse interest rates along with a possible drop in consumption and an increase in unemployment, lead him to believe that the rally experienced in the first part of the year will be difficult to replicate in the months ahead.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.