What’s in store for the global economy in 2023?

The key question for the year ahead is whether central banks will be able to curb inflation without cratering economies in an environment of high volatility and geopolitical tension

Economists have had a poor track record of predicting recessions since the 1970s, unlike the markets themselves. But once again, there is widespread agreement among economists that the combination of inflation, interest rate hikes, weakness in the Chinese economy and geopolitical uncertainty has a high probability (over 60%) of leading to a global recession. This is why contrarians say that if economists are predicting a recession, it most likely won’t happen.

2022 was supposed to be the year when the world made a full recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic with the lifting of containment measures and a return to normalcy. Instead, it was a year marred by war, inflation, energy and commodity price shocks, droughts and floods. It was also a year when central banks struggling to tame inflation finally said goodbye to near-zero interest rates, cheap energy and economic globalization as we knew it.

Predictions are hard to make in the current environment, says Yves Bonzon, chief investment officer for Julius Baer, the Swiss private banking group. “2022 has been a dismal year for economic forecasts and 2023 will not be any easier to read,” he writes in his latest analysis. With all the “black swans” [extremely rare events with very negative consequences] and “gray rhinos” [slowly emerging, predictable yet ignored threats] emerging over the last few years, forecasting has become even more difficult. But the key question for 2023 is whether central banks will be able to temper inflation. Perhaps they won’t be able to get it down all the way to the 2% target, but perhaps enough to avoid a recession, or at least a deep one. Even though there are significant regional differences, the stakes are very high everywhere.

After first asserting that inflation would be short-lived, central banks collided with price levels not seen since the 1980s, prompting them to aggressively hike interest rates at a pace not seen in 40 years. In the US, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates (the price of money) from 0.25% in March to 4.5% by the end of the year. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank (ECB) raised rates from 0% to 2.5% between July and December. Everyone expects the rate hikes to continue on both sides of the Atlantic until inflation approaches the 2% target. In other words, these two central banks are scrambling to recover ground lost due to major miscalculations, and perhaps restore a measure of credibility.

Inflation has begun to moderate in the United States and in some eurozone countries like Spain, but it’s still in double digits in Germany, the United Kingdom and Italy. A number of economies in Latin America, as well as in Eastern and Central Europe began raising rates to address inflationary pressures well before some of the developed economies. While none have been able to bring inflation down, those who acted early have generally performed better than expected.

Economists expect inflation to moderate in the next six months as the impacts of this year’s energy and food price shocks begin to fade. But more turbulence in energy markets cannot be ruled out, says Edoardo Campanella, an economist with UniCredit. “The global gas market is so stressed that it will be unable to accommodate any increase in European demand next year, assuming the expected recovery in Asian demand materializes,” he said. With no end in sight to the war in Ukraine, the coming months will bear heavily on energy prices next winter.

Just like it takes six to 18 months for an economy to feel monetary policy impacts, fiscal stimulus measures also have lagging effects. Rescue packages such as the €200 billion German fund to help ease the energy crisis and the bulk of the Next GenerationEU recovery funds have yet to trickle down into the economy. The US experience is similar. After the government sent stimulus checks to US households and expanded unemployment benefits, household savings soared from a $1 trillion pre-pandemic level to $4.7 trillion in the second quarter of 2022, according to Bloomberg.

Wage increases

Stefan Hofrichter, head of economics and strategy at Allianz, believes that other factors will feed high inflation, including the underlying rate – the rate of inflation that would be expected to eventually prevail in the absence of economic slack, supply shocks, idiosyncratic relative price changes, or other disturbances. Hofrichter notes factors like the expected wage increases in key countries; the fragmentation of the global economy, which makes supply chains more expensive and reduces supply in key products such as semiconductors; and the fight against climate change, which causes energy prices to spike during the transition to a more sustainable and efficient model. In this light, it seems almost certain that central banks will continue to tighten monetary policy throughout 2023.

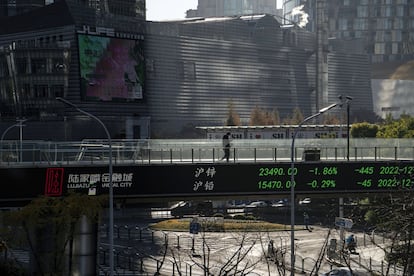

In its global investment outlook for 2023, BlackRock Investment wrote, “The Great Moderation, the four-decade period of largely stable activity and inflation, is behind us. The new regime of greater macro and market volatility is playing out. A recession is foretold; central banks are on course to overtighten policy as they seek to tame inflation.” Past history would indicate that central banks will not be able to reduce double-digit inflation levels without triggering a recession. Since the effects of trends like widespread remote work arrangements and the digital economy have not yet been quantified, things may be different this time, but we should be prepared for the worst. Some of the data points to a slowdown in activity – the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), an index of the prevailing direction of economic trends in the manufacturing and service sectors, has been below 50 for several months, which is consistent with a contraction in activity. Likewise, the eurozone countries and the US are experiencing declines in industrial production, a leading indicator of a drop in GDP. On a positive note, the markets reacted enthusiastically to China’s recent decision to end its zero-Covid policy. But coexistence with the coronavirus may be more difficult than expected, and global economic activity could be disrupted by new waves of infection like the ones experienced by China throughout much of 2022.

So far, a strong labor market has cushioned the global economy from a hard landing, a resilience that surprised many experts who were predicting a recession in the major economies as early as 2022. But higher borrowing costs due to interest rate hikes and reduced household disposable income are an obvious drag on activity. When you add in a downturn in corporate profit growth and the subsequent slowdown in investment, everything points to an eventual recession. “When the macroeconomic analysis and your own indicators are saying the same thing, it’s wise not to ignore them,” said Neil Shering, chief global economist at Capital Economics. “If it’s any consolation, the recession should not be very deep. We are not facing a pandemic or financial crisis like we were during the 2020 and 2008 recessions.” UniCredit Chief International Economist Daniel Vernazza is forecasting a mild recession followed by a weak recovery, and expects that stagflation will threaten the major economies once they move out of negative territory.

Fitch Ratings estimates that for the US and the eurozone, each percentage point increase in interest rates reduces GDP by half a point. The ECB has already raised rates by 2.5% and the Federal Reserve has hiked rates by 4.25%. Fitch notes that the real estate market is already feeling the impacts of the higher cost of credit, with mortgage applications dropping by 8% in 2022. Although forecasts vary, economists generally agree that the recession in the United States could be around -0.5%, while the eurozone and the United Kingdom will experience a deeper recession (between -1.5% and -2%) due to heavier impacts from the energy crisis and disrupted trade with Russia.

Experts say that China, the world’s second largest economy, will escape a recession, but estimate that in 2023, its economy will remain at mid-2021 levels after almost two years of lost growth due to the pandemic. Forecasts indicate sluggish growth for China in the first half of 2023 as the country adjusts to the end of the zero-Covid policy, which experts believe won’t be fully felt until April, followed by a significant rebound in the second half of the year. Nevertheless, Goldman Sachs believes the Chinese economy will experience significant changes that will affect its growth fundamentals. These include recent US restrictions on imports of Chinese-made advanced semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment, which are expected to reduce China’s GDP by 0.25% in 2023 and a cumulative 1.7% by 2026. A recent Goldman Sachs report said that much of the slowdown in Chinese growth in recent years is due to a lower potential GDP growth of 4.2%, and that “[China’s] potential [GDP] growth will slow to 3% over the next decade, due to its weak demographics and productivity, as well as the long slump in the real estate market.” Consequently, experts are increasingly saying that Beijing will not overtake the United States as the world’s leading economic power before 2060, which would be 30 years later than previously expected.

Pessimistic forecasts

In light of all these indicators, experts have lowered their growth forecasts to a global GDP of roughly 2.2% in 2023. According to the Institute of International Finance (IIF), after adjusting for base effects, global GDP will grow by just 1.2% next year, levels not seen since the Great Recession (with the exception of the 2020 pandemic), and consistent with what economists consider to be a de facto global recession.

Now that money is no longer free, risk once again comes at a price. The crisis unleashed in the UK when the markets punished former Prime Minister Liz Truss’s fiscal plans clearly revealed the harsh reality of Brexit and a zero tolerance for unsustainable programs. In 2023, the sovereign risk of two countries will be under the microscope: Italy, with public debt levels of around 150%, and Brazil, which will have a new government on January 1. But past experience has shown that a single episode of market stress can be contagious. That threat will surely return, since some central banks like the Federal Reserve have already begun the process of reducing the size of their balance sheets and the ECB has announced that it will stop buying government debt as of March, submitting it once again to market forces. With more public debt and higher financing costs, fiscal adjustment plans will be back on the table and investors will be keeping a close eye on risk premiums.

“Welcome to the Godot recession,” wrote Credit Suisse’s Ray Farris, evoking the famous play by Samuel Beckett. Pessimism can be seductive and considering what happened in 2022, it’s easy to get carried with gloom-and-doom predictions for 2023. The only sure thing is that uncertainty will dominate any scenario, and perhaps the recession that seems inevitable may never arrive, like Godot.

“Black swans” and “gray rhinos”

Erik Nielsen, Global Chief Economist at UniCredit, says, “There are no limits to what one can imagine happening in 2023.” The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and even the eruption of the La Palma volcano in Spain’s Canary Islands have elicited comparisons to the “black swans” described by Lebanese-American author, Nassim Taleb. His 2007 book, The Black Swan, focuses on the extreme impact of rare and unpredictable events, and the human tendency to retrospectively find data-centered explanations for these events. However, some think that the events of the past few years are more like gray rhinoceroses – obvious high-probability, high-impact threats like environmental, technological and health risks – that are ignored or minimized until it is too late. The gray rhino concept was first presented by American author Michele Wucker at the 2013 World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos, Switzerland.

UniCredit’s Nielsen leans more toward the obvious gray rhinos in the world today, which he places in two categories – political or economic threats. Of the gray rhinos with at least a 20% probability, Nielsen highlights US politics and the dangers of a House of Representatives controlled by an increasingly populist Republican Party. Nielsen believes this political environment could end up triggering a debt ceiling crisis “that would make the volatility caused by Liz Truss’s fiscal plans in the UK look like child’s play.” He is also concerned about shifting alliances in the Middle East, with China cozying up to Saudi Arabia, as witnessed by President Xi Jinping’s recent trip to Riyadh. Among the economic gray rhinos, Nielsen points to the possibility of a recession in the second half of 2023 due to persistent inflationary pressure, deteriorating household purchasing power and the impacts of monetary policies. “If this [a recession] happens, central banks would have to reverse their current monetary policies,” said Nielsen. On the other hand, there is an equal possibility that a significant upturn in economic activity could force monetary authorities to continue raising interest rates: 6%-7% in the US and 4%-5% in the eurozone. Nor can we rule out a new energy supply shock or contagious Chinese real estate problems spreading beyond its borders, said Nielsen.

Saxo Bank, a Danish investment bank, often issues some of the most provocative forecasts around. While some discount Saxo’s reports as sensationalist, Chief Investment Officer Steen Jakobsen and his team anticipated Brexit in 2016, the stock market crash in 2008 and the rise of Bitcoin in 2017. Saxo Bank’s predictions for 2023 include: French President Emmanuel Macron’s resignation and the ascendancy of Marine Le Pen to the Elysée Palace; a Labor Party victory in the UK and a new referendum to reverse Brexit; the price of gold at $3,000 an ounce; new price controls on commodities; and the exit from the International Monetary Fund of OPEC countries, China and India. How to recap all of this? Check back with us in a year.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.