Maurice Ravel, the ‘heathen’ composer, premieres music 150 years after his birth

The New York Philharmonic is commemorating the composer’s anniversary with an exhibition and the world premiere of a work recently identified through the personal diary of his friend, the Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes

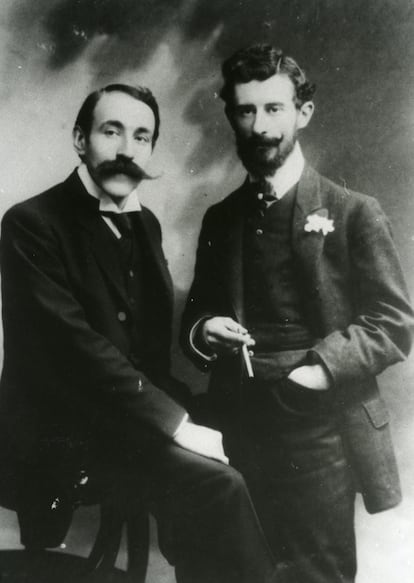

“He is a most unfortunate being, a superior intelligence and artist who would be worthy of better fortune. He is also highly complex, with a blend of a medieval Catholic and a satanic heathen, yet governed by a love of art and beauty that also guides him and makes him feel candidly.” Few descriptions capture Maurice Ravel as completely, poetically, and precisely as this entry in the diary of Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes, written on November 1, 1896, after the two shared a tearful audition of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde prelude with the Lamoureux Orchestra.

No one knew better this 21-year-old dandy — in the Baudelairean sense — who debated the colors of ties and shirts with the utmost seriousness while being fascinated by poetry, fantasy, and all things precious, rare, paradoxical, and refined. Ravel, a misunderstood musician, was only beginning to forge his creative voice after being expelled from piano and harmony classes at the Paris Conservatory.

It is the 150th anniversary of Ravel’s birth. But the most significant commemoration of his sesquicentennial will not take place in his native Ciboure or in Paris, where he grew up and flourished, but on the Upper West Side of Manhattan — a city he visited in 1928. David Geffen Hall, home of the New York Philharmonic, is hosting an exhibition in his honor, which was inaugurated last Monday, as well as a concert on March 13, where Venezuelan conductor Gustavo Dudamel will premiere Sémiramis. “It is a composition from 1902 that has been identified thanks to an entry in Viñes’ diary, which is also featured in the New York exhibition,” explains Màrius Bernadó, speaking from his office at the University of Lleida.

This musicologist and professor is immersed in an ambitious project to reconstruct the entire concert career of Ricardo Viñes. Viñes was the preeminent pianist of the French avant-garde, premiering in Paris much of the finest piano music of his time, including works by Debussy, Ravel, Satie, and Falla.

“At the Musicology Laboratory of the University of Lleida, we are working on pianoNodes: Ricardo Viñes in Concert, a project that will serve as the foundation for a portal based on linked open data,” Bernadó explains. “It will bring together all available knowledge on Viñes, allowing users to access the resources of his rich documentary collection, cross-reference data, conduct searches, and generate visualizations, maps, timelines, etc.”

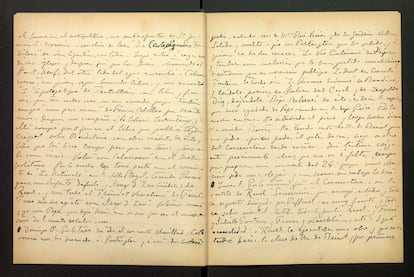

Bernadó is also focused on Viñes’s extraordinarily rich unpublished diary. “It spans more than 7,000 pages written across 30 notebooks, in which the pianist recounts his first three decades in the French capital, from his arrival in October 1887 to an abrupt end in August 1915,” he says.

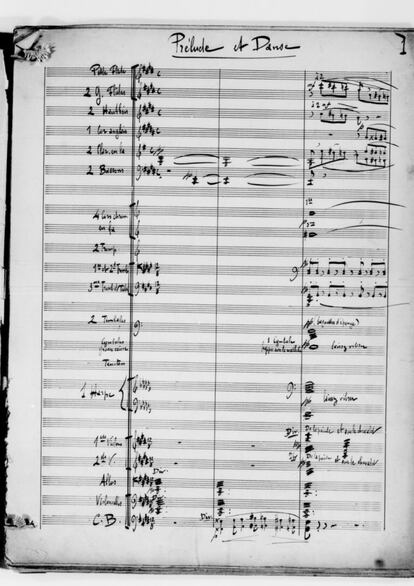

The manuscript of Sémiramis was acquired in 2000 by the National Library of France, along with other early compositions, from Ravel’s home in Montfort-l’Amaury. “But the score is unsigned and lacks the usual markings of the French composer, so it was not clear whether the music was his or someone else’s,” Bernadó notes.

Ravel used the exact same libretto as the cantata Sémiramis by his colleague Florent Schmitt, which had won the Prix de Rome in 1900. He set the beginning to music, composing a prelude and a dance set during the coronation celebration of the Assyrian chief Manasseh in the exotic gardens of the palace of Assur, presided over by Semiramis, Queen of Babylon. He added only the tenor aria sung by Manasseh in the first scene, where he expresses his love and fascination for Sémiramis, but did not continue with the remaining three scenes of the libretto. Ravel submitted the work in 1902 for the Paris Conservatory’s composition prize, but was unsuccessful.

The musicologist presents Viñes’ diary entry from April 7, 1902: “In the morning I went to the Conservatoire to hear Ravel’s cantata Sémiramis which was rehearsed, studied and played by the orchestra conducted by [Paul] Taffanel: it is very beautiful and full of an oriental flavor. The whole Ravel family was there, and [Gabriel] Fauré and Juliette Toutain, [Henry] Février and [Charles] Koechlin, etc!"

No other record of this composition exists — neither in the conservatory’s administrative archives nor in the press of the time, as noted by François Dru, director of the Ravel Edition, who has prepared the score of the prelude and dance for its world premiere in New York. The 1902 performance described by Viñes took place during a Thursday morning class at the Paris Conservatory. However, to hear the complete work as composed by Ravel — including the prelude, the dance, and the tenor aria for Manassès — we will have to wait until the end of the year. The Orchestre de Paris will perform it in December at the Philharmonie de Paris, under the baton of Alain Altinoglu.

A quick glance at Ravel’s new score reveals a musician with a unique personality. It shows a 27-year-old composer who had absorbed the harmonic force of Wagner, the colourful beauty of Rimsky-Korsakov, and the orchestral details of Franck and Debussy. However, Sémiramis does not fully showcase his creative potential, as it was written to appeal to a conservative jury. It bears similarities to the three cantatas he composed as unsuccessful entries for the Prix de Rome between 1901 and 1903 — Myrra, Alcyone, and Alyssa. On his fifth and final attempt in 1905, he was unfairly eliminated in the first round, triggering the scandal known as the Ravel Affair. The controversy ultimately led to the resignation of the conservatory’s director, Théodore Dubois, and the appointment of Ravel’s teacher and advocate, Gabriel Fauré, in his place.

However, Ravel’s musical innovations had begun much earlier, with Viñes as an exceptional witness. “The composer and the pianist met in November 1888, when they were both 13 years old and studying in Charles de Bériot’s piano class at the conservatory. They soon became inseparable, sharing hobbies such as reading and reciting poetry, painting, and visiting art galleries and auction houses. Together, they discovered the world and life. Even as their respective mothers met to speak Spanish, the two teenagers experimented with new Spanish harmonies and rhythms by playing four-handed piano,” Bernadó explains.

From that experience emerged one of Ravel’s first significant compositions, the Habanera from Sites auriculaires, which he later orchestrated as the third movement of his Rapsodie espagnole. This creative journey continued with Alborada del gracioso, in both piano and orchestral versions, and extended to his opera L’heure espagnole (1911), which will be staged next month at Les Arts in Valencia, and his globally renowned Boléro (1927).

Bernadó also highlights that this year marks the 150th anniversary of Viñes' birth, an occasion officially recognized by the Catalan regional government and supported by the Lleida City Council. In addition to numerous commemorative activities — concerts, seminars, and publications — the ultimate goal is to preserve and improve access to this rich yet long-neglected heritage.

“The premiere of Ravel in New York is a clear example of the opportunity and the need to invest in heritage to ensure its preservation, and also to generate knowledge that allows the design and creation of cultural products,” says Bernadó.

The majority of Viñes’ extensive documentary collection has been entrusted to Lleida by his descendants through successive donations following his death in 1943. However, it now requires urgent conservation efforts. A significant portion of his concert programs is already available as open-access resources in the institutional repository of the University of Lleida. Next, posters, press clippings, photographs, correspondence, and personal writings will be digitized, along with the reconstruction of his remarkable musical library, which remains dispersed across multiple North American and European collections. Building on the momentum of the anniversary commemoration, this vast trove of information will be integrated and interconnected using digital humanities tools.

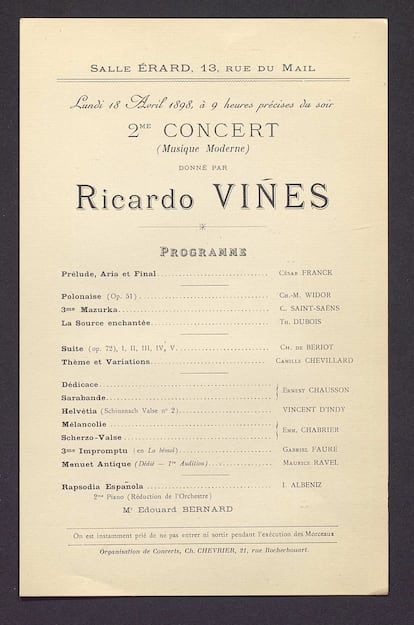

“Viñes kept up to 15 copies of the program for the concert where he premiered Ravel’s first publicly performed composition, Menuet antique, at the Salle Érard in Paris in 1898. It’s fortunate that he had the habit of saving everything,” says Bernadó, as he presents the Viñes Collection at the University’s Library of Literature. Shortly after, Viñes also premiered the now-famous Pavane pour une infante défunte (1899) and, most notably, Jeux d’eau (1901). The latter revolutionized piano writing with its blend of dazzling virtuosity and delicate impressionist nuance, which clearly impressed Debussy, as noted by Arbie Orenstein in his classic monograph Ravel: Man and Musician.

Following these early successes, Viñes and Ravel formed Le Cercle des Apaches, an association of musicians, writers, and artists who gathered every Saturday. The group later included figures like Manuel de Falla and Igor Stravinsky. Viñes went on to premiere Miroirs (1904) and Gaspard de la nuit (1908), the latter inspired by the haunting, ephemeral nocturnal imagery of three poems by Aloysius Bertrand, which Viñes himself had lent to Ravel.

However, their relationship began to deteriorate in the 1920s due to disagreements over the interpretation of Ravel’s works. In fact, Viñes’s recordings from 1929 to 1936 no longer included any of Ravel’s compositions. In the final years of his life, the composer found an ideal pianist in Marguerite Long, for whom he wrote Le tombeau de Couperin and the Concerto in G. At the same time, Ravel began experiencing the early symptoms of a degenerative neurological disease, which would ultimately reduce him to a shadow of himself — an image masterfully rendered with irony and precision by Jean Echenoz in the closing pages of his novel Ravel (2006).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.