The ‘pure men’ who made Europe tremble

A new book investigates the history of the Christian sect that gave rise to the Spanish Inquisition

Around 800 years ago, Europe suffered one of the greatest crises in its history, a seismic shift that shook the very foundations of the rigid institutions of the Middle Ages; the monarchy and the Catholic Church. Simony (the buying and selling of ecclesiastical privileges), nepotism (the appointment of relatives to positions of power), and the Nicolaitan system (the inheritance of church offices) were gnawing at Rome and its civil, military, and religious satellites. The powerful hoarded food while the peasantry faced fruitless harvests caused by massive floods and a sudden drop in temperatures. Roads were filled with wandering, starving crowds, and bandits terrorized those who had nothing left. Saladin captured Jerusalem, the Crusaders returned defeated, and the kings of Castile and Aragon suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Alarcos. God had abandoned his flock, it was thought.

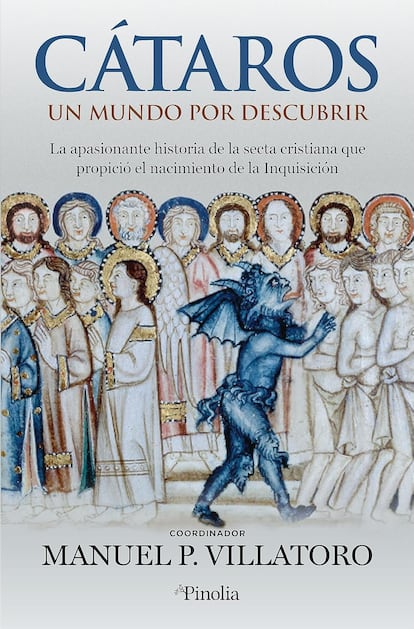

Faced with this situation, an irate spiritual and political movement, born in the most wretched strata of society, emerged with overwhelming force in the heart of the Continent. Its members were known as heretics, of whom the Cathars would become the greatest and most powerful exponent. the Church — for it was a Church — of Catharism advocated a return to the original values of the Gospel. It took such deep root among the dispossessed that it could only be eradicated through the use of terror and the murder of tens of thousands of innocents. Burned alive or pierced by spears, Cathars, Waldensians, and Hussites resisted beyond all comprehension, giving rise to the worst of repressions. The entertaining and instructive Cátaros. Un mundo por descubrir (in English, Cathars. A World to Discover), coordinated by Manuel P. Villatoro, brings together 18 texts by great specialists who analyze a spiritual earthquake that gave rise to the appearance of the Inquisition.

“In the mid-12th century, reports emerged of minority groups or sects defending the ancient and remote origins of a Church that had remained secret since the time of the apostles,” the authors write. The first signs appeared in the cities of Cologne and Liège. Ecclesiastical authorities reacted swiftly: “Fires at will to burn heretics.”

From a doctrinal standpoint, Catharism — the term Cathar comes from the Greek and means “pure” — is the result of a symbiosis of 12th-century European religious and intellectual currents. It was influenced by Manichaeism and dualism, doctrines that revolved around the perpetual struggle between Good and Evil. They also believed in reincarnation after a process of self-improvement that would lead them to divinity. The quickest way to achieve this was to lead an ascetic life. They accepted only one sacrament, the consolamentum, a symbolic ceremony that combined baptism, communion, and extreme unction. Interestingly, they were vegan, but they could eat fish, as they considered it a product of the sea, the rivers, and the cleansing water. The bishop was their highest representative, under whom were the deacons (priests) and the faithful, or perfects. They accepted euthanasia and suicide as a way to accelerate the reincarnation process. They held conclaves modeled after those in Rome.

This mystical-religious movement shook Western Europe, but above all the Church, which saw its power and influence threatened. An alliance with the French Crown allowed for the creation of a massive army to eradicate it. The extermination of these believers was called the Albigensian Crusade, another name by which they were known. The Latin root alb means “white” or “pure,” although many experts also link the name of this sect to the French city of Albi, one of its centers of power.

The first thing the Church did was launch a smear campaign. They were accused of promoting moral anarchy, sexual permissiveness, organizing orgies, adulterous same-sex relationships, and practicing incest.

In the 12th century, France was not unified. Large and powerful feudal estates, almost kingdoms, remained. This was the case in Languedoc, ruled by Count Raymond VI. The nobleman, always eager for power, had his sights set on the riches of the Catholic Church. For this reason, he embraced the Cathar faith. He was excommunicated in 1207 and invaded shortly afterward by the troops of the French King Louis VII, spurred on by Pope Innocent III. Raymond tried to back down when he saw the armies approaching and withdrew his support for the heretics. But it was too late. The flame of rebellion had been ignited, and the Pope declared a crusade.

From then on, kings like Peter II of Aragon, victor of the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, and Raymond VI himself, who finally decided to confront the crusaders, entered the fray. Their defeat at the Battle of Muret on September 12, 1213 — Peter II died in the battle, ending Aragonese expansion beyond the Pyrenees — marked the beginning of the end for the Albigensians. Their followers were forced to scatter and hide in remote mountainous areas or take refuge in the fortresses that still supported them. In Toulouse alone, one of the Cathar cities, the inquisitors John of Saint-Pierre and Bernard of Caux interrogated more than 5,000 people, who in turn denounced another 10,000. “The interrogations gathered confessions extracted by force, and it is often difficult to differentiate the real facts from the fictitious confessions of those tortured,” the authors recall.

They conclude: “From that moment on, the Cathar heresy still had some outbreaks that finally culminated in the events known as the Bonfires of Montségur, where the last Cathars officially lost their lives in March 1244. With the armed conflict quelled, the pen began to wield power, and the Albigensians were mythologized in the centuries to come as these good Christians who had stood up to the all-powerful papacy.” The legend had begun.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.

More information

Archived In

Últimas noticias

Aquilino Gonell, former Capitol sergeant: ‘If it hadn’t been for the police, the US would be a dictatorship’

A hybrid building: Soccer pitch, housing, and a shopping mall

Europe urges Trump to respect Greenland following annexation threats

Science seeks keys to human longevity in the genetic mixing of Brazilian supercentenarians

Most viewed

- Alain Aspect, Nobel laureate in physics: ‘Einstein was so smart that he would have had to recognize quantum entanglement’

- Mexico’s missing people crisis casts a shadow over World Cup venue

- Why oil has been at the center of Venezuela-US conflicts for decades

- Trump clarifies who is ultimately in charge in Venezuela: ‘Me’

- Alvin Hellerstein, a 92-year-old judge appointed by Bill Clinton, to preside over Maduro’s trial in New York