On the trail of the only medieval crusade in the Iberian Peninsula

A new documentary picks up the archaeological trail of the largest military confrontation in Medieval Spain

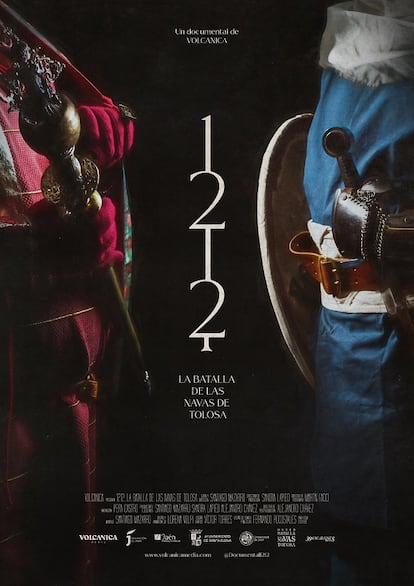

It was the only medieval campaign on Spanish soil that was declared a crusade by Rome, and thousands of knights from all over Europe responded to the call. The Christians knew it simply as Las Navas, while the Muslims called it “the Punishment.” Both armies confronted each other, with a three to one numerical advantage to the Almohads. As professor of medieval history at the University of Extremadura Francisco García Fitz asserts, the battle marked the “beginning of the end” of Moorish power in the Iberian Peninsula. Now, a new documentary, 1212. La batalla de las Navas de Tolosa (1212: The battle of Las Navas de Tolosa) — premiered in Spain —, uses the archaeological, military, and historical traces to reconstruct this enormous combat with which the Christians sought to bring the border that divided both powers south to the Guadalquivir River, while the Muslims sought to raise it to the Tagus River to protect the epicenter of their power, namely, the cities of Seville and Córdoba.

The Battle of Las Navas, also known as the Battle of the Three Kings — Castile, Aragon, and Navarre — was fought near the town of Santa Elena in Andalusia. About 10,000 Christian fighters, led by the Castilian king Alfonso VIII, fought roughly 30,000 warriors of the caliph Muhammad al-Nasir. However, the final confrontation, which occurred on July 16, was preceded by other unforeseen skirmishes that occurred during the Christian troops’ rapid march south from Toledo.

Álvaro Soler, head of Armament at the Royal Armory of Madrid, explains that it was “a crucial battle in medieval history, in an extremely unstable world.” At that time, there were five existing Christian kingdoms (Portugal, León, Castile, Navarre, and Aragon), which were in constant conflict with one another. The other half of the peninsula was occupied by the Muslim polity of Al-Andalus, dominated by the Almohads, who were made up of a federation of Berber tribes. They were “a revolutionary movement that advocated the renewal of Islam by returning to the original prophetic time,” as historian Maribel Fierro of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) describes it. “Their fanaticism led them to declare jihad [holy war] against the Almoravids, the previous Andalusian dynasty,” she adds.

Pope Innocent III in Rome was aware of the danger of the more than likely collapse of Christendom’s western frontier in the event of a Muslim victory. The Almohads, originally from the north of the Sahara, had become one of the greatest empires in the world, and their intention was to spread throughout the north of the Iberian Peninsula. After subduing the Andalusians and Almoravids, the Christian kingdoms represented the last obstacle to their northern expansion. But Alfonso VIII of Castile was willing to prevent it. “He is one of the great monarchs of the second half of the 12th century,” recalls García Fitz. “When he solved his territorial problems with León, he sealed a series of military alliances, especially with Navarre and Aragon, to face the imminent Almohad threat together,” the professor says.

The complete Christian defeat against the Muslims at Alarcos in 1195 soured Alfonso’s character. “He carried it deep inside, deep in his soul,” says Soler. Throughout that time, the archbishop of Toledo, Jiménez de Rada, encouraged him to seek revenge. The cleric thus became a fundamental character in what would happen in 1212, since, in addition to traveling around Europe recruiting knights, he convinced Pope Innocent III to sign the bull that declared the “Holy Crusade for the Iberian Peninsula,” the only Hispanic crusade in medieval history. “It was a call to fight for any Christian, regardless of their kingdom, so hundreds of crusaders arrived from England, France, Germany, Italy, and other kingdoms in Europe. It was a truly remarkable mass of people,” says García Fitz.

On May 20, after five days of marching from Toledo, the Christian army reached the Sierra Morena mountain range. The castle of Malagón — which ongoing archaeological surveys have shown was of large proportions — was attacked by European crusaders. As was the custom during the crusades, all occupants of the castle were murdered. “That was beyond the pale for the peninsular kings, especially since the castle had already surrendered,” says Soler. Thus, tension built up among the Christian troops, and it exploded with the taking of the castle of Calatrava, the next fortress on the road. The defenders surrendered after two days of intense fighting and after learning what had happened in Malagón. According to Manuel Retuerce, director of the castle of Calatrava site, the remains of the only soldier killed in the military operation were found in 1985. He was a Muslim armed with a spear and had several arrows stuck in him.

The foreign crusaders demanded the execution of all the castle’s inhabitants despite having laid down their arms. Alfonso VIII refused to kill them and let the defenders leave with their belongings and horses. A large proportion of the crusaders from northern Europe were indignant and decided to return to their kingdoms. Discouragement spread, but the attitude changed when the king of Navarre, Sancho VII “the Strong,” who had not arrived in time to join the rest of the contingent in Toledo, showed up with 200 knights and hundreds of foot-soldiers and archers.

From there, the troops of the three monarchs continued their joint march towards the south. García Fitz suspects that the caliph refused a direct confrontation. “He wanted to block [the Christians] in the Sierra Morena, because it is totally impossible to fight a battle in the mountains, given their complex topography,” the professor says. The Almohad castle of Castro Ferral was located on one of the highest points in the mountain range — archaeological interventions have also uncovered that it was a large construction, not just a watchtower — and served as a checkpoint. From there, the Christians discovered that all the mountain passes had been taken by Muslims and that it would be impossible to descend with horses and impediments without being seen and massacred. However, according to tradition, a local shepherd showed them a path that the Almohads did not control. “It is perfectly possible,” says historian Irene Montilla. “There have always been border people [Christian or Muslim] who knew the passes well, and the shepherds were among them,” Álvaro Soler says. The next morning, the caliph discovered to his horror that the crusaders had crossed the mountains at night and had established their camp very close to his, García Fitz adds.

The material trace of this battle has remained hidden for eight centuries, until a team of archaeologists and historians began work “to understand this legacy.” “For the first time, an archaeological approach is being carried out on all its sites,” says Soler. “This is how we are able to accurately locate the roads along which the troops moved, the location of the tents of the archbishop, the kings, and the caliph. It also allows us to recover the material culture of that time, such as the weapons that were used,” explains Fierro. “Unfortunately,” Soler laments, “the project is shaped by looting. It is a very sad fact that taints any reading of the battle. An arrowhead is a worthless object if you take it out of context, and the looting has been devastating, especially at the end of the 20th century.”

Historical sources speak of Alfonso, “he of Las Navas”, and al-Nasir, “the prince of believers,” but archaeological data testifies that thousands of people who were armed only with bows and arrows fought on that day, and that they represented the lowest levels of society, although they are barely mentioned in the history books. Their deaths, however, “contributed in the same way to forging the legend of one of the most famous battles in our history,” the documentary recalls, although it has done so with few means — there are no horses in the recreations of the battle, despite the importance of cavalry in combat — and it mistakes the type of helmets that the Christians wore, covering the heads of some extras with armor more typical of the French and English armies of the 15th century. “We have already told them to cut it,” one of the experts consulted in the film told EL PAÍS. “The historical story is good, but it is as if a soldier from the Napoleonic era suddenly appeared in the Spanish Civil War.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.