Children’s literature can also have very young authors

Publishers and non-profit groups in Spain, Portugal, Australia and Ireland share the same conviction: that the best writers of children’s books are the kids themselves

Babies know how to do just the bare minimum: breathe, eat, cry. And, hopefully, sleep. For everything else, however, they need support. Little by little, they learn how to dress, wash, stack building blocks and think for themselves.

Their independence also grows around books. First, they listen to them. Then, they read them on their own. They even choose the books they want, selecting them from the shelves right at ground level. But typically, whatever the little one chooses, it will have been written by someone who is already grown up.

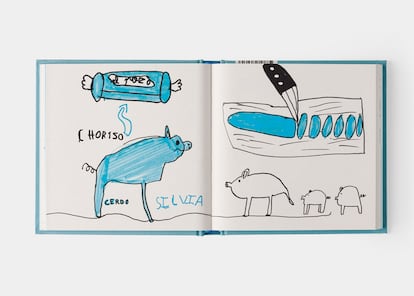

“A staggering amount of children’s and young adult literature is published [each year]. And the fact that [the production process doesn’t involve] the children themselves is striking. The books are supposed to be talking about their future and the future of the world… and yet, they can’t have an opinion,” reflects Vicente Ferrer Azcoiti, editor of Media Vaca, a publisher based in Valencia, Spain. That’s why, for years now, he’s been asking them questions and helping them create their own literary works. He and a handful of editors from different countries share the same conviction: that the best authors of children’s books are children themselves.

This concept is championed by the Portuguese organization Fábrica de Histórias (“Factory of Stories”), the German Buchkinder, the Irish-led Kids’ Own Publishing Partnership, as well as its Australian sister organization. The locations, nuances and legal framework (publishing houses vs. non-profit organizations) may vary, but all subvert the usual chain of command: the children are in charge of the plot, illustrations and, sometimes, even the layout. The adults remain in the shadows, coordinating and contributing where they can.

Thanks to the workshops hosted by these non-profits and publishing houses, thousands of children in different corners of the planet have already fulfilled the dream that so many adults pursue throughout their lives: admiring their own book on a shelf. Some even have two.

Adrián E., Iona and Iriana released their debut novel when they were barely six years old. Together with a few other classmates, they have their signatures on a children’s book titled ¡Que vuelvan los estorninos! (translated from the Spanish as Let the Starlings Return!), published by Media Vaca. And now, at the age of eight, in another workshop, the kids are currently preparing their second publishing venture: a story written and drawn by 25 students from the Benimaclet Municipal School, in Valencia. Each creator is tasked with a small piece of the story.

“All children have the right to contribute to the culture around them; their voices should be valued and celebrated. They’re innately creative and we don’t give them enough space, opportunities and recognition to help them see that their inventiveness has no limits. Seeing themselves as part of a real project that endures – like a book – supports this idea,” notes Anna Dollard, the creative director of Kids’ Own Publishing’s Australian sister company.

She explains that her workshops, similar to those held by Media Vaca or Fábrica de Histórias, typically last several weeks. Professional artists participate, working with their tiny colleagues to foster their ideas and bring them to life. Once a consensus is reached, the process begins. The children create, but they also adjust, tweak, monitor and sign off on any progress; they, of course, must provide the final approval. “The level of respect has to be the same as with professionals,” Ferrer explains. Finally, the result appears on paper, for creators, families, teachers and — if possible — libraries or bookstores.

The spark can come from the organizations themselves, or from schools, museums, libraries, or other entities that request their services. Rui Andrade, who runs Fábrica de Histórias with Raquel Salgueiro, sets only a few conditions: that the workshop be held during school hours and that it have some connection to the local community, or to what’s being taught. “It doesn’t have to be more important than other tasks, but [the project] must have a soul,” he maintains.

From there, the range of possibilities explodes: there are projects with dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of young authors. Andrade previously spoke with each of the 2,500 participants in one of his latest publications. Their ages range from toddlers to full adolescence. Along the way, parents — even grandparents — can get involved.

The Portuguese organization has expanded the process to include theater and film. They also nurture young directors, animators and soundtrack composers. Everything ultimately culminates in what Dollard summarizes as follows: “Texts and illustrations come to life through an emergent, iterative and communal artistic process, where ideas come together, agreements are reached, compromises are made and a meticulously unique story is born.”

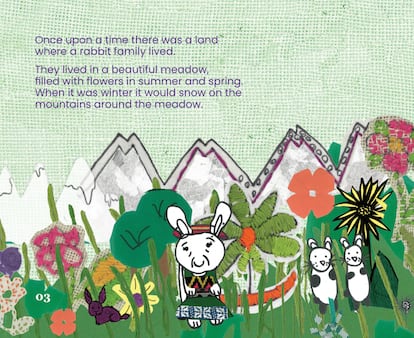

The adult mind would have hardly been able to conceive the story entitled On the Fly and its Usefulness. Childlike in the best sense of the word, it was developed by Media Vaca with seven-year-old creators from the Benimaclet Municipal School. Nor would it have thought of Jump Seriously – written and drawn by students from the Casa da Criança de Tires, in conjunction with Fábrica de Histórias – or The Cheeky Rabbit, one of the projects that Dollard is most proud of: every Saturday, for five weeks, a Hazara community (a Persian-speaking Afghan ethnic group) on the outskirts of Melbourne shared their stories and customs. The grandmothers also taught the rest of the group their traditional embroidery. They all debated which book they would collectively write and illustrate… but the deciding vote fell to the children. It was agreed that they would be the ones in charge, with the support of their families.

Thus was born the epic story of a young rabbit who leaves his happy home in search of adventure. In the end, he winds up returning, relieved, after dodging a few dangers. The work, which is read from right to left, includes collages with fabrics and images of typical objects from the Hazara community.

When it was published, John Gulzari, the expert who advised the process, hailed it as one of the first opportunities to share stories in the Hazaragi language, which is primarily oral and repressed by the Taliban. And the director of Kids’ Own Publishing considers it a pillar of her organization, especially in a country as multicultural as Australia. Her mission, after all, is to tell the stories of those who are not heard. Children’s literature sometimes defines its audience with the phrase “for everyone.” And, with this initiative, it’s about making this ideal come true.

These publications – at least, at the start – are the work of many people. “Collective works,” Ferrer calls them. “They reflect a moment of collaborative work and the children’s real interests. No matter how hard an adult tries to imitate it, the original will always be more authentic,” Dollard adds. And it turns out that, in the process, young authors even teach a thing or two to their supposed guides: the Australian expert notes that children’s creations include fewer “messages” and “morals” than most books aimed at them. In the face of the “growing homogenization of the sector,” they offer stories and voices that are as original as they are unexpected. Furthermore, Dollard emphasizes, “they’re not born from strategic plans or sales imperatives.”

A cause for joy, of course. But also a source of difficulty, as Rui Andrade clarifies: his model is as laudable and inclusive as it is expensive… and almost impossible to cover with market revenues. The Portuguese publisher has known this since 2012 through Fábrica de Histórias. But two years before the organization began, he opened Cabeçudos, the first bookstore specializing in children’s and young adult books in Lisbon. And he believes that the low profitability explains why many more similar experiences aren’t emerging around the world.

“Working with children and publishing their works requires an ethical framework that contrasts with the commercial publishing model. Sales revenue doesn’t – and can’t – support this community activity. Which brings us back to taking children’s creativity and ideas seriously,” Dollard argues. “We should consider what kind of publishing market we want [and] what books are really for,” Ferrer adds.

For now, the financial accounts often don’t add up. And these programs must rely on voluntary efforts or public funds. The balance of satisfaction, however, is more than just positive. In a conversation with Rui Andrade, a teacher shared what a creative child had confessed to her: “I [am] no longer afraid of drawing.” And one of the young authors of The Cheeky Rabbit video-called her grandmother in Afghanistan to show her the finished product.

Kids’ Own Publishing’s slogan reads: “Changing the world, one book at a time.” By taking very small steps… but also some very big ones. Just like the artists.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.