John Fogerty, rock legend: ‘I love music. I feel good when I play and it makes me feel good when I see people happy’

The former frontman for Creedence Clearwater Revival, which broke up in 1972 after five years of dazzling success, has put the turbulent history of the legendary band behind him. A symbol of a historic moment in American rock, he has just released a new album

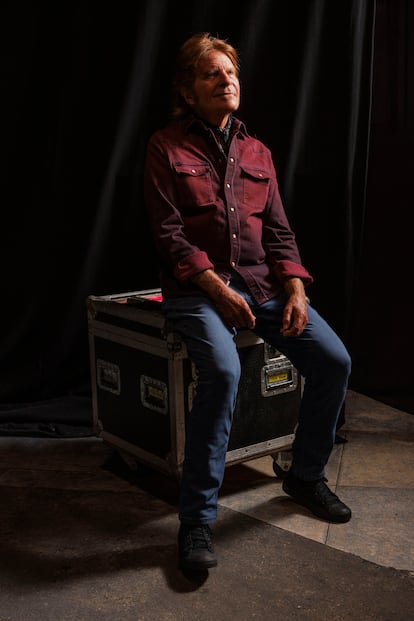

Sitting on a sofa, John Fogerty, 80, is waiting in the depths of a hotel conference room. Suddenly, in slow motion, the Berkeley-born singer-songwriter stands up and excuses himself. “Do you mind if I say hello to my granddaughters before we start?” he asks. His tone is polite and almost hurried.

The interview begins 45 minutes late and he didn’t expect his two granddaughters to appear through the door right when the last journalist of the morning arrived. They cuddle their grandfather without raising their voices — they know he’s working.

Taking small steps, Fogerty returns to the sofa, sits down and shakes hands. “Excuse me, it’s been a restless morning and there’s nothing better for a grandfather than seeing his granddaughters. I’m sorry I’m so late.”

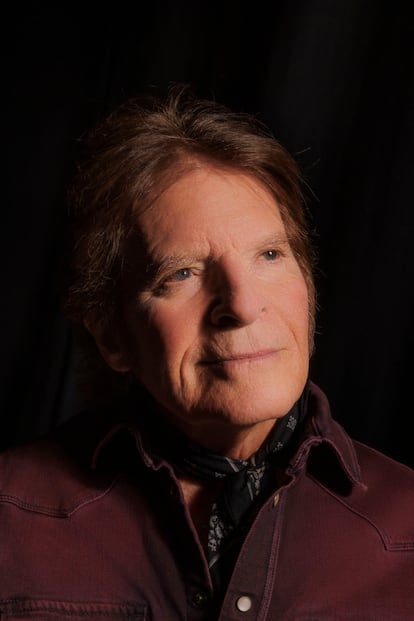

The speaking voice of one of the most recognizable singers in the history of popular music — whose songs for the legendary rock band Creedence Clearwater Revival are often among the most played on rock radio shows around the world — sounds like that of a goldfinch. It’s fragile and mellow… quite different from the sharp, edgy voice that pierces the soul with every chorus.

This living legend of American rock is dressed in his usual outfit: light-colored jeans and a dark blue flannel plaid shirt that matches his neckerchief. It’s the “Fogerty look,” which is as recognizable on stage as Angus Young in schoolboy pants, or Iggy Pop bare-chested. Polite and calm, his brown eyes stare at you. One can only marvel at their power, but also their mystery. “I love music. I dunno... I feel good when I play and it makes me feel good when I see people happy.” These are the reasons he offers as he explains why he continues to go full throttle. He has a new album with Concord Records, Legacy: The Creedence Clearwater Revival Years, and a tour recently brought him to Europe over the summer.

The meeting with Fogerty took place in a hotel in London’s Soho district. The English capital had dawned with a radiant and cheerful sun, as if it wanted to pay its own tribute to the visit of the great Creedence Clearwater Revival songwriter, whose effusive and luminous songbook seems like a reason to be happy. “If I’m honest, it makes me smile now to hear that the songs [I wrote and performed with the band] are so celebrated,” he acknowledges. “And, if that’s true, it’s because I’ve regained the publishing rights to my own songs.”

“Hearing these songs spoken about so well is very different from hearing [the same thing] 10 years ago,” he admits. “Back then, there was a shadow over my whole past. I was unhappy… but now, it makes me feel really good.” As its name suggests, Legacy: The Creedence Clearwater Revival Years reinterprets his legacy with the band, for which he was always the sole songwriter. “It’s a celebration. I wanted to show the joy I feel playing these songs with my family. The album became a kind of family affair.”

His wife, Julie Fogerty, is the executive producer of the album. And it features his sons, Shane and Tyler. “I wanted to pass on my heritage to them. It was a wonderful feeling,” he sighs, repeating the word “wonderful” twice while closing his eyes.

I love music. I dunno... I feel good when I play it and it makes me feel good when I see people happyJohn Fogerty

Today, Fogerty seems happy. But for many years, he was the complete opposite. He used to be a man at odds with the world… and, especially, with his own band, which he disowned. He even admitted that he fantasized about smashing its gold records with a baseball bat.

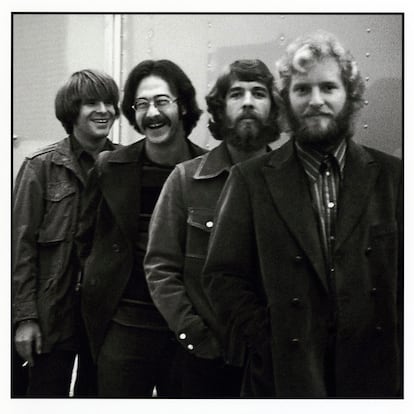

Fogerty had his reasons. He had created and led a group he formed in the late 1960s with his older brother Tom (guitarist), Doug Clifford (drummer) and Stu Cook (bassist). And, in record time — between the summer of 1968 and Christmas of 1970 — the band released six albums and redefined the map of American music, establishing itself as a leading reference point in the countercultural era.

The bandmates reached their peak during the years of the Beach Boys, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones… and bang, they immediately fell. The owner of their record label, Saul Zaentz, tricked them into slave-like contracts and kept all the rights to the songs. The group disbanded in 1972. But that’s when the ordeal escalated: the rest of the band — including Fogerty’s brother — turned on him and decided to ally with Zaentz, in order to make some money from a songbook as lucrative as Creedence’s. Fogerty stood his ground against everyone and saw another blow dealt to him: they agreed to sell the songs to television commercials without his permission.

As he recounted — in great detail and with much venom — in his memoir, Fortunate Son (2015), this whole hell led him to ruin. He was unwilling to play his songs and he became a depressed alcoholic. “My bandmates always wanted to be Hollywood heartthrobs, not musicians,” he wrote in his autobiography. “We were a rock’n’roll band… not IBM or something like that. It was almost a romantic flight of fancy; ‘We don’t need a contract. We have each other’s word!’”

He stopped speaking to everyone. Events illustrating the resentment on both sides occurred: when Creedence Clearwater Revival entered the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1993, Fogerty surrounded himself not with his former bandmates, but with Bruce Springsteen and Robbie Robertson. In response, Doug Clifford and Stu Cook — now performing without Tom Fogerty, who died in 1990 — decided to create Creedence Clearwater Revisited. For almost three decades, this band played songs written by the author they repudiated, who didn’t receive a single dollar in royalties.

But that’s all over now. John Fogerty has reclaimed what’s his. “Unfortunately, I haven’t spoken to them since everything happened. All communication is always done through my lawyers,” he says calmly. “All my experience has led me to give this advice to my children: when it comes to contracts, you should have a good lawyer. Find someone competent who can read everything before [you sign it].” And, with a serious expression — without shying away from a topic he didn’t want to talk about for many years — he adds, after a pause: “And then, I don’t know, I should probably tell you something else: you should work with people you like and who seem to be helping you out. Don’t waste your time with people you don’t like or who are just wasting your time. It often happens that you run into people like that.”

The Creedence Clearwater Revival case has gone down in music history as an example of the demons that can lurk behind a great success. A horror story in which a musician — on par with rock’s greatest songwriters — ends up rejecting his own music and suffering martyrdom. And yet, none of that drama can tarnish the songbook of a band that achieved a definitive sound. Just as there’s the concept of the “great American novel,” if it were applied to music in an attempt to find the “great American song,” this group would be a contender with all the credentials. Because Creedence is like setting the adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn to music all at once: exuberant compositions of no more than four minutes each, which mix primitive rock, swamp music, as well as rhythm and blues. The author notes that the songs’ powerful riffs maintain “a rhythm of sand and Vaseline.”

“When I was young, I kept listening to music from my record collection at home,” he tells EL PAÍS. “[These singers] had a certain hook. I’m talking about artists who influenced me, like Lightning Hopkins, Howlin’ Wolf and Bo Diddley. They were all people who had that unique Louisiana touch. It’s a mysterious touch, because pop music tends to be more direct and tries to maintain the same rhythm all the time, while this other kind of music has more mystery. There was a different cadence that I aspired to.”

The merit was achieving that radiant yet swampy sound from the depths of El Cerrito, a neighborhood on the outskirts of San Francisco, during the Summer of Love (that is, in the late 1960s, pushing against the current of Californian psychedelia). “We were certainly different,” Fogerty explains. “Most of San Francisco was psychedelic. Everything revolved around drugs a lot. Some of the most famous bands were there, like the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane.”

“There was a lot of improvisation,” he continues, “and you have to be very good at improvising to the point where the audience can follow you, in a jazz way. I think a lot of that [psychedelic] stuff was boring and there were a lot of audiences who felt the same way… but people pretended because, deep down, they had no idea. I was in the middle of all that and I felt like nobody really knew what was going on. They were looking for a soundtrack to disorientation… and I didn’t want that.”

Fogerty — who has always rejected drugs and once called Timothy Leary, the father of LSD and guru of hippiedom, a “moron and a buffoon” — shifts a little on the couch and adds: “I wanted to play more focused music and present the songs as complete entities. I tried to be concise. And I wanted to be as energetic as possible. I wanted people to want to go for the next song because there was a rhythm they couldn’t shake.”

In this way, Creedence was the United States’ best response to the resounding success of The Beatles. In an interview with EL PAÍS back in 2014, Fogerty himself claimed that his band was the best in history after the Fab Four. However, at the time, the Liverpool band was always pitted against another 100% American rival: The Beach Boys. Thus, two Californian bands had reached the American pinnacle in the golden age of pop.

During the interview with Fogerty, not even 10 days had passed since the death of Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys’ main songwriter. And Fogerty offered a clear opinion about one of his competitors for the title of greatest American songwriter: “Brian Wilson was wonderful, the best songwriter in history. He was huge. We met a couple of times. I think his music is the best. I sing his songs all the time.”

“I tell my children, as far as contracts go, you should have a good lawyer who knows how to read everything before [you sign it].”John Fogerty

Putting aside the competition, Fogerty is an American emblem. A recognizable standard-bearer, he experienced the turbulent era of the counterculture, criticized the Vietnam War and now observes the present from his old age. “When I was young, in those years, there was hope for the future. And I always thought that was a wonderful thing. In the late 1960s, they called us ‘hippies.’ But we thought we could change the world and we truly believed it. Maybe we were naive, but youth culture reflected that. For a long time, we’ve shied away from it.”

At the beginning of the 20th century, he — alongside Neil Young, Springsteen, R.E.M. and Pearl Jam — also led the 2004 Vote for Change tour, which called for the departure of George W. Bush from the White House following the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Today, he has no doubts about his diagnosis for what his country is going through: “Perhaps it’s because the American political situation is very similar to that of the 1960s, but I see more and more young people today starting to talk and feel the same way about the concepts of justice and equality. Mr. Trump reminds me a lot of Mr. Nixon.” But, like so many American artists who know that Trump acts with retaliation, he speaks without wanting to dwell too deeply on the situation.

His gaze tenses: “I think Mr. Trump likes things the way he wants them… and maybe it’s time to do something about that.” It was then that his press agent, sitting on another sofa — hearing the word “Trump” again — stood up to end the interview.

Politely, Fogerty gives EL PAÍS a couple more minutes before he says, “My granddaughters are waiting for me.” The two are standing at the back of the spacious room. He gives a half-smile when he realizes this. However, before the interview ends, he confesses that one song he would have loved to write would have been When a Man Loves a Woman (1966), by Percy Sledge. And, among so many unbeatable songs that he’s composed, he assures EL PAÍS that he’ll stick with Joy of My Life (1997), which is included on his album from the same year, Blue Moon Swamp. “It’s the song I wrote for my wife,” he notes.

And then, John Fogerty — the living legend, the symbol of the hippie era… but also the husband and grandfather — stands up with a huge smile to greet his granddaughters.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.